Consistent Hashing in Action

- 背景介绍

- 基本介绍

- What Is Hashing?

- Introducing Hash Tables (Hash Maps)

- Scaling Out: Distributed Hashing

- The Rehashing Problem

- The Solution: Consistent Hashing

- History

- Basic technique

- Comparison with rendezvous hashing and other alternatives

- Complexity

- gcc 4.8.5 std::hash 实现

- std::hash

- 一致性哈希实现

- 一致性哈希的 Q&A

- Refer

背景介绍

Consistent Hashing is a distributed hashing scheme that operates independently of the number of servers or objects in a distributed hash table. It powers many high-traffic dynamic websites and web applications.

In recent years, with the advent(出现) of concepts such as cloud computing(云计算) and big data(大数据), distributed systems(分布式系统) have gained popularity and relevance.

One such type of system, distributed caches(分布式缓存) that power many high-traffic dynamic websites and web applications, typically consist of a particular case of distributed hashing. These take advantage of an algorithm known as consistent hashing.

基本介绍

In computer science, consistent hashing is a special kind of hashing technique such that when a hash table is resized, only n/m keys need to be remapped on average where n is the number of keys and m is the number of slots. In contrast, in most traditional hash tables, a change in the number of array slots causes nearly all keys to be remapped because the mapping between the keys and the slots is defined by a modular operation.

Consistent hashing evenly distributes cache keys across shards, even if some of the shards crash or become unavailable.

Consistent hashing 是一种特殊的哈希技术,主要用于解决分布式系统中的数据分配问题。其主要优点是能够在节点数量变化时,最小化需要重新分配的数据数量。这对于缓存系统特别重要,因为在节点增加或减少时,我们希望尽可能减少因为重新哈希带来的缓存失效。

在传统的哈希表中,如果哈希表的大小改变(例如,因为添加或删除了节点),几乎所有的键都需要重新哈希到新的位置。这对于缓存系统来说是不可接受的,因为这意味着大量的缓存失效和重建。

而在一致性哈希中,当添加或删除节点时,只有一小部分的键会被映射到新的节点,大部分的键仍然会被映射到原来的节点。这就意味着,即使有节点崩溃或者变得不可用,也只会影响到一小部分的键。

此外,一致性哈希还能保证数据在节点之间的均匀分布。这是通过将每个节点和每个键都映射到一个环形的哈希空间来实现的。每个键都被分配到顺时针方向上的第一个节点(也就是最近的节点)。因此,即使节点的数量发生变化,键也能被均匀地分配到各个节点。

总的来说,一致性哈希能够在节点数量变化时,最小化需要重新分配的数据数量,并且保证数据在节点之间的均匀分布。这使得它非常适合用于分布式缓存系统。

一致性哈希的特点:

- 平衡性。不同 Key 通过算法映射后,可以比较均衡地分布到所有的节点上

- 单调性。当有新的节点上线后,系统中原有的 Key 要么还是映射到原来的节点上,要么映射到新加入的节点上,不会出现从一个老节点重新映射到另一个老节点

- 稳定性。当服务发生扩缩容的时候,发生迁移的数据量尽可能的少

What Is Hashing?

A hash function is a function that maps one piece of data—typically describing some kind of object, often of arbitrary size—to another piece of data, typically an integer, known as hash code, or simply hash.

For instance, some hash function designed to hash strings, with an output range of 0 .. 100, may map the string Hello to, say, the number 57, Hasta la vista, baby to the number 33, and any other possible string to some number within that range. Since there are way more possible inputs than outputs, any given number will have many different strings mapped to it, a phenomenon(现象) known as collision(碰撞). Good hash functions should somehow “chop and mix” (hence the term) the input data in such a way that the outputs for different input values are spread as evenly as possible over the output range.

Hash functions have many uses and for each one, different properties may be desired. There is a type of hash function known as cryptographic hash functions, which must meet a restrictive set of properties and are used for security purposes—including applications such as password protection, integrity checking and fingerprinting of messages, and data corruption detection, among others, but those are outside the scope of this article.

Non-cryptographic hash functions have several uses as well, the most common being their use in hash tables, which is the one that concerns us and which we’ll explore in more detail.

Introducing Hash Tables (Hash Maps)

Imagine we needed to keep a list of all the members of some club while being able to search for any specific member. We could handle it by keeping the list in an array (or linked list) and, to perform a search, iterate the elements until we find the desired one (we might be searching based on their name, for instance). In the worst case, that would mean checking all members (if the one we’re searching for is last, or not present at all), or half of them on average. In complexity theory terms, the search would then have complexity O(n), and it would be reasonably fast for a small list, but it would get slower and slower in direct proportion to the number of members.

How could that be improved? Let’s suppose all these club members had a member ID, which happened to be a sequential number reflecting the order in which they joined the club.

Assuming that searching by ID were acceptable, we could place all members in an array, with their indexes matching their IDs (for example, a member with ID=10 would be at the index 10 in the array). This would allow us to access each member directly, with no search at all. That would be very efficient, in fact, as efficient as it can possibly be, corresponding to the lowest complexity possible, O(1), also known as constant time.

But, admittedly, our club member ID scenario is somewhat contrived(人为的). What if IDs were big, non-sequential or random numbers? Or, if searching by ID were not acceptable, and we needed to search by name (or some other field) instead? It would certainly be useful to keep our fast direct access (or something close) while at the same time being able to handle arbitrary datasets and less restrictive search criteria.

Here’s where hash functions come to the rescue. A suitable hash function can be used to map an arbitrary piece of data to an integer, which will play a similar role to that of our club member ID, albeit with a few important differences.

First, a good hash function generally has a wide output range (typically, the whole range of a 32 or 64-bit integer), so building an array for all possible indices would be either impractical or plain impossible, and a colossal(巨大的) waste of memory. To overcome that, we can have a reasonably sized array (say, just twice the number of elements we expect to store) and perform a modulo operation on the hash to get the array index. So, the index would be index = hash(object) mod N, where N is the size of the array.

Second, object hashes will not be unique (unless we’re working with a fixed dataset and a custom-built perfect hash function, but we won’t discuss that here). There will be collisions (further increased by the modulo operation), and therefore a simple direct index access won’t work. There are several ways to handle this, but a typical one is to attach a list, commonly known as a bucket, to each array index to hold all the objects sharing a given index.

So, we have an array of size N, with each entry pointing to an object bucket. To add a new object, we need to calculate its hash modulo N, and check the bucket at the resulting index, adding the object if it’s not already there. To search for an object, we do the same, just looking into the bucket to check if the object is there. Such a structure is called a hash table, and although the searches within buckets are linear, a properly sized hash table should have a reasonably small number of objects per bucket, resulting in almost constant time access.

With complex objects, the hash function is typically not applied to the whole object, but to a key instead. In our club member example, each object might contain several fields (like name, age, address, email, phone), but we could pick, say, the email to act as the key so that the hash function would be applied to the email only. In fact, the key need not be part of the object; it is common to store key/value pairs, where the key is usually a relatively short string, and the value can be an arbitrary piece of data. In such cases, the hash table or hash map is used as a dictionary, and that’s the way some high-level languages implement objects or associative arrays.

Scaling Out: Distributed Hashing

Now that we have discussed hashing, we’re ready to look into distributed hashing.

In some situations, it may be necessary or desirable to split a hash table into several parts, hosted by different servers. One of the main motivations for this is to bypass the memory limitations of using a single computer, allowing for the construction of arbitrarily large hash tables (given enough servers).

In such a scenario, the objects (and their keys) are distributed among several servers, hence the name.

A typical use case for this is the implementation of in-memory caches, such as Memcached.

Such setups consist of a pool of caching servers that host many key/value pairs and are used to provide fast access to data originally stored (or computed) elsewhere. For example, to reduce the load on a database server and at the same time improve performance, an application can be designed to first fetch data from the cache servers, and only if it’s not present there—a situation known as cache miss—resort to the database, running the relevant query and caching the results with an appropriate key, so that it can be found next time it’s needed.

Now, how does distribution take place? What criteria(标准) are used to determine which keys to host in which servers?

The simplest way is to take the hash modulo of the number of servers. That is, server = hash(key) mod N, where N is the size of the pool. To store or retrieve a key, the client first computes the hash, applies a modulo N operation, and uses the resulting index to contact the appropriate server (probably by using a lookup table of IP addresses). Note that the hash function used for key distribution must be the same one across all clients, but it need not be the same one used internally by the caching servers.

The Rehashing Problem

This distribution scheme is simple, intuitive, and works fine. That is, until the number of servers changes. What happens if one of the servers crashes or becomes unavailable? Keys need to be redistributed to account for the missing server, of course. The same applies if one or more new servers are added to the pool; keys need to be redistributed to include the new servers. This is true for any distribution scheme, but the problem with our simple modulo distribution is that when the number of servers changes, most hashes modulo N will change, so most keys will need to be moved to a different server. So, even if a single server is removed or added, all keys will likely need to be rehashed into a different server.

So, most queries will result in misses, and the original data will likely need retrieving again from the source to be rehashed, thus placing a heavy load on the origin server(s) (typically a database). This may very well degrade performance severely and possibly crash the origin servers.

The Solution: Consistent Hashing

So, how can this problem be solved? We need a distribution scheme that does not depend directly on the number of servers, so that, when adding or removing servers, the number of keys that need to be relocated is minimized. One such scheme—a clever, yet surprisingly simple one—is called consistent hashing, and was first described by Karger et al. at MIT in an academic paper from 1997 (according to Wikipedia).

Consistent Hashing is a distributed hashing scheme that operates independently of the number of servers or objects in a distributed hash table by assigning them a position on an abstract circle, or hash ring. This allows servers and objects to scale without affecting the overall system.

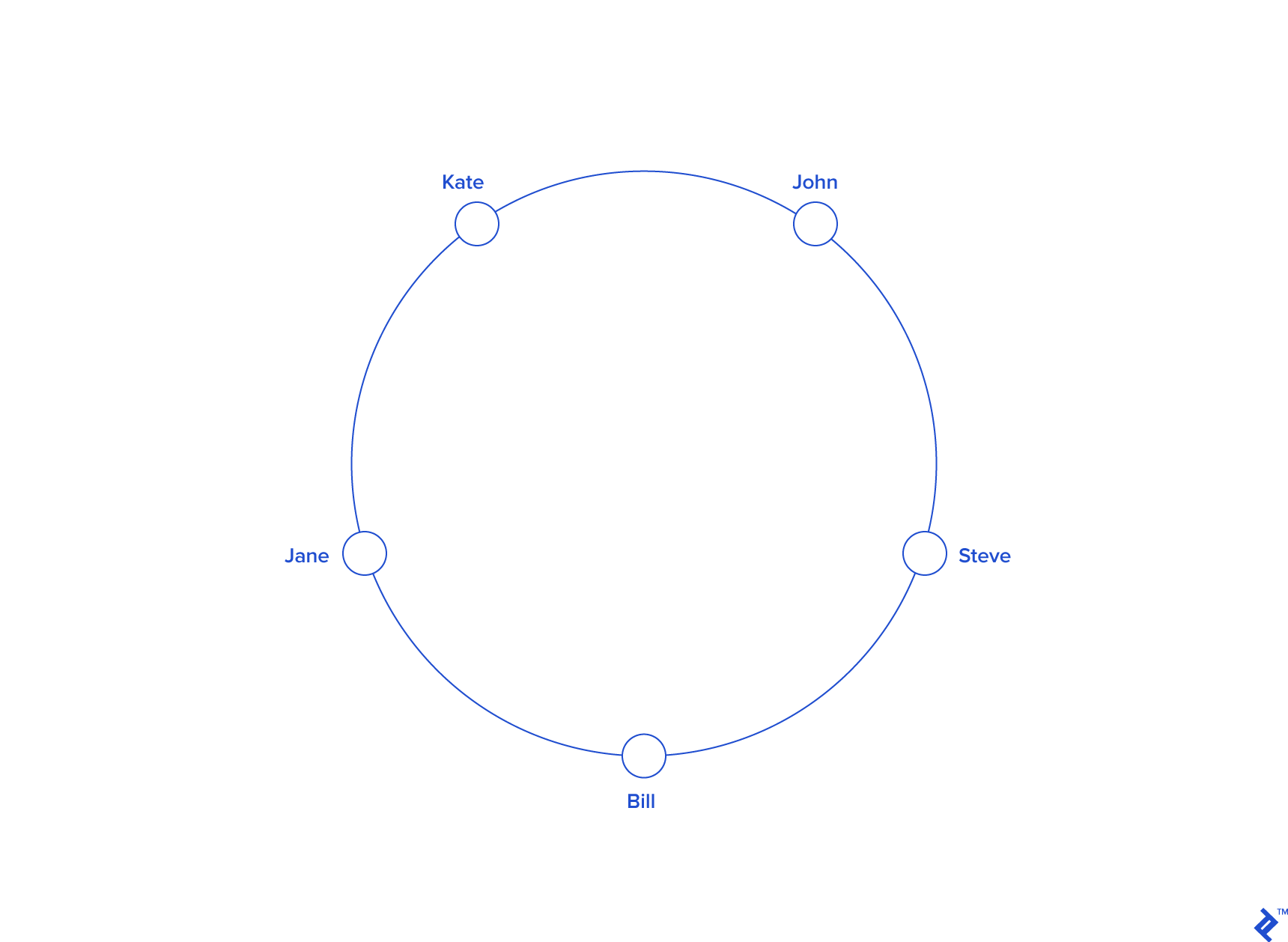

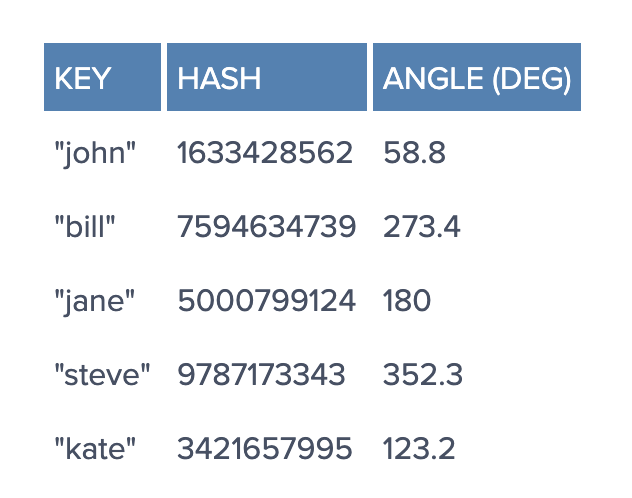

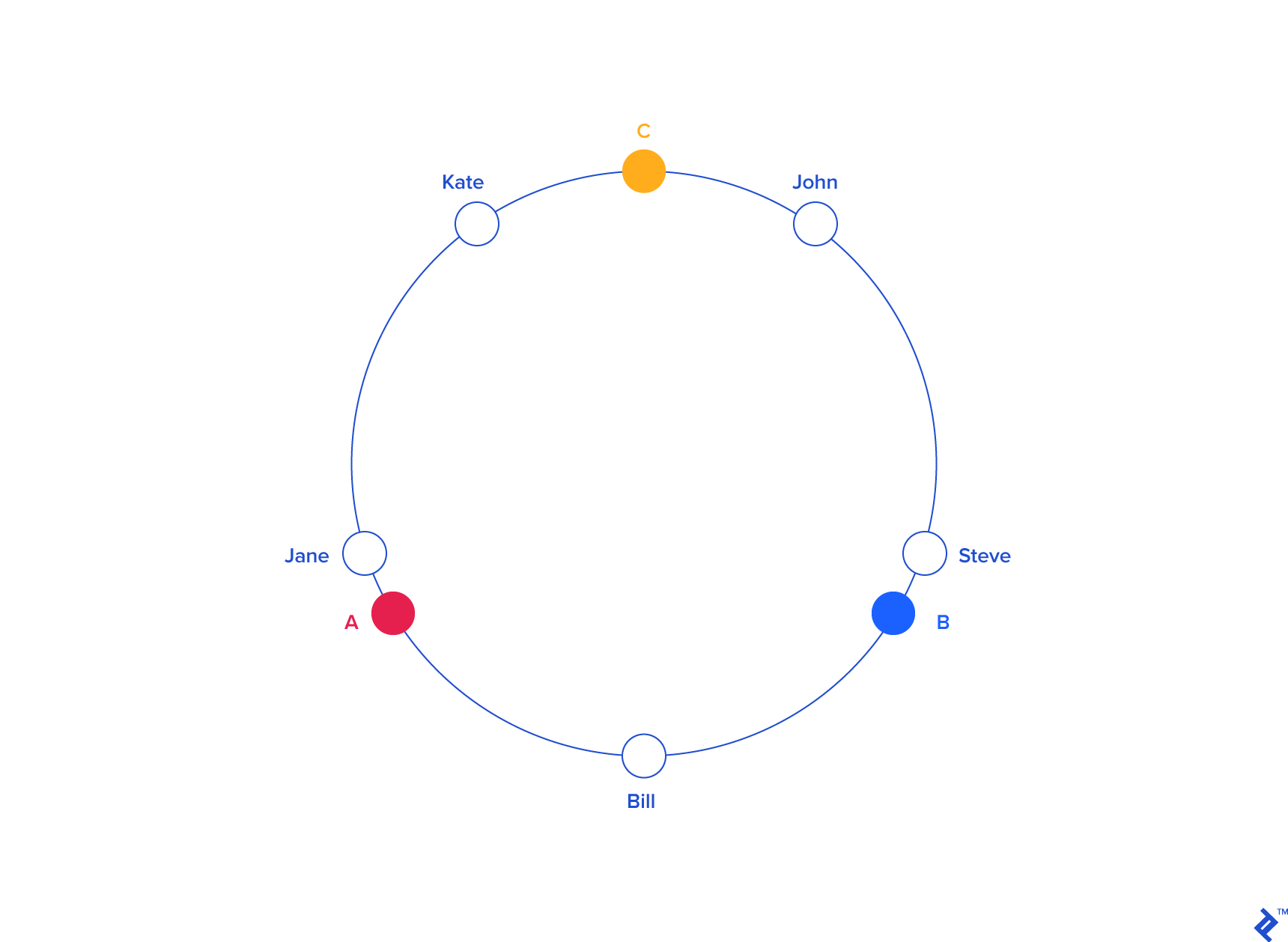

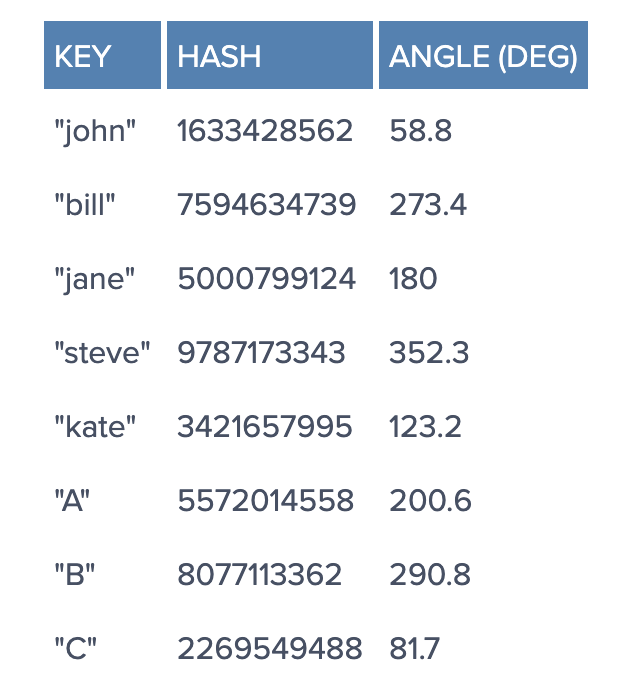

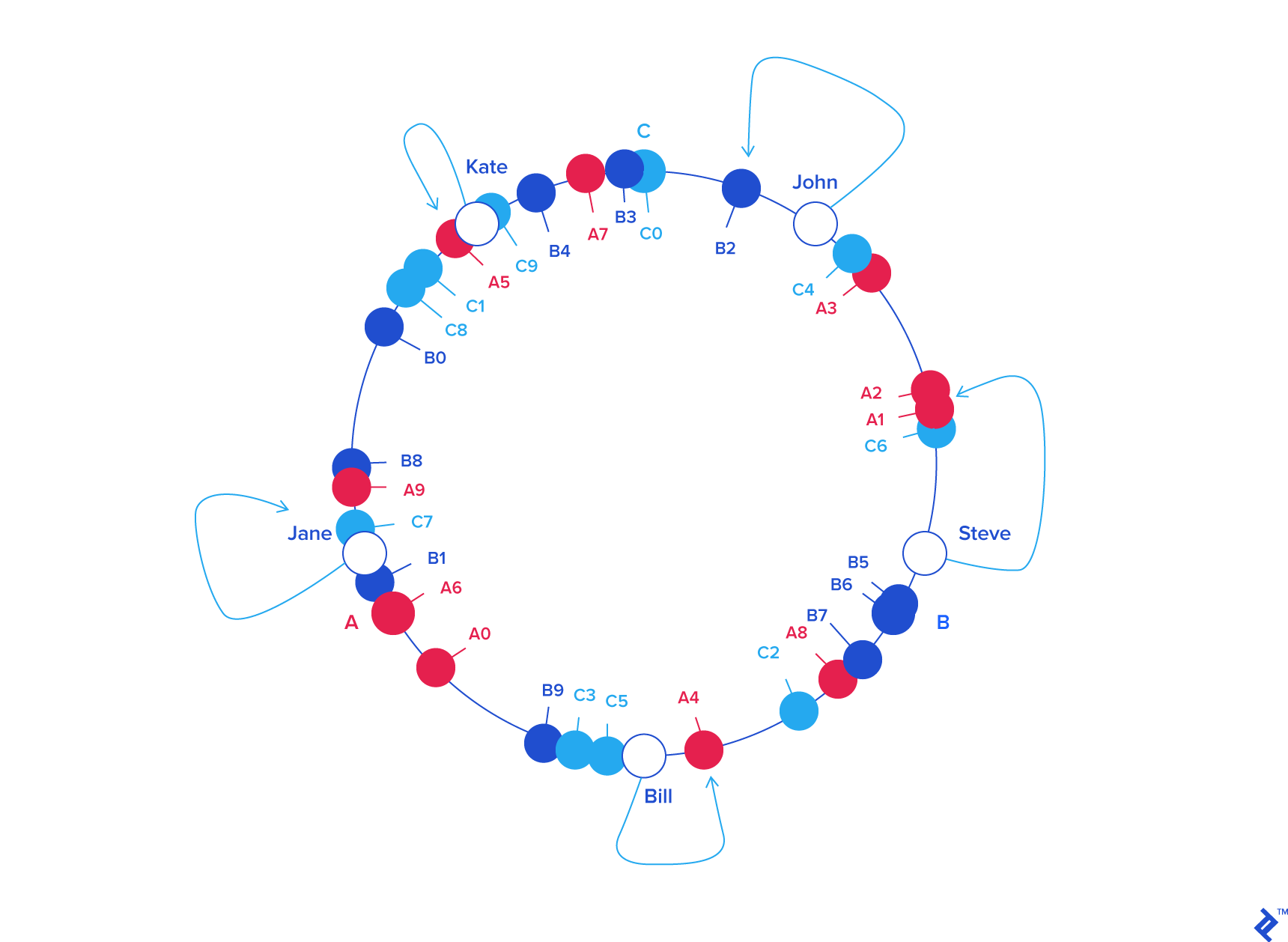

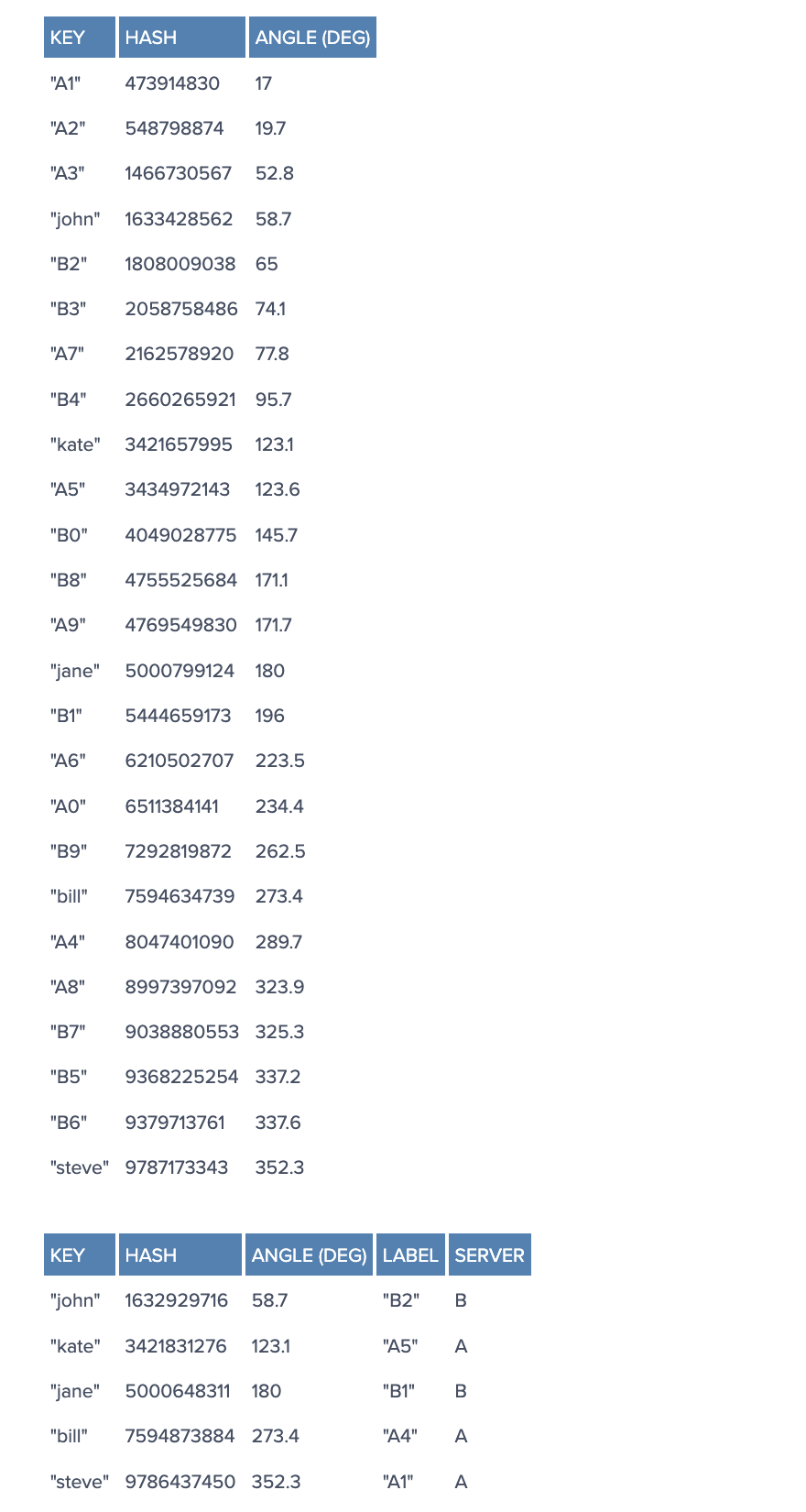

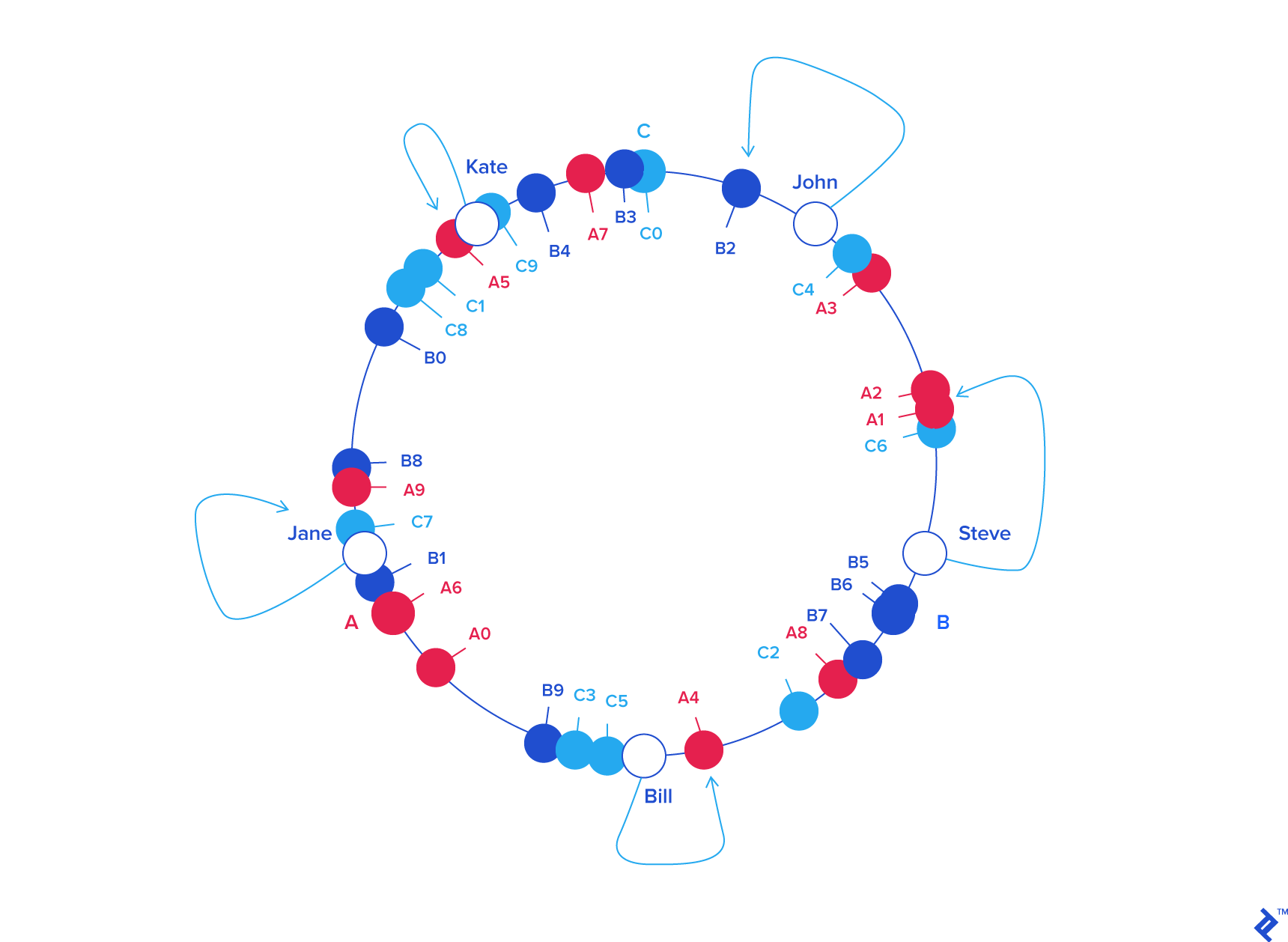

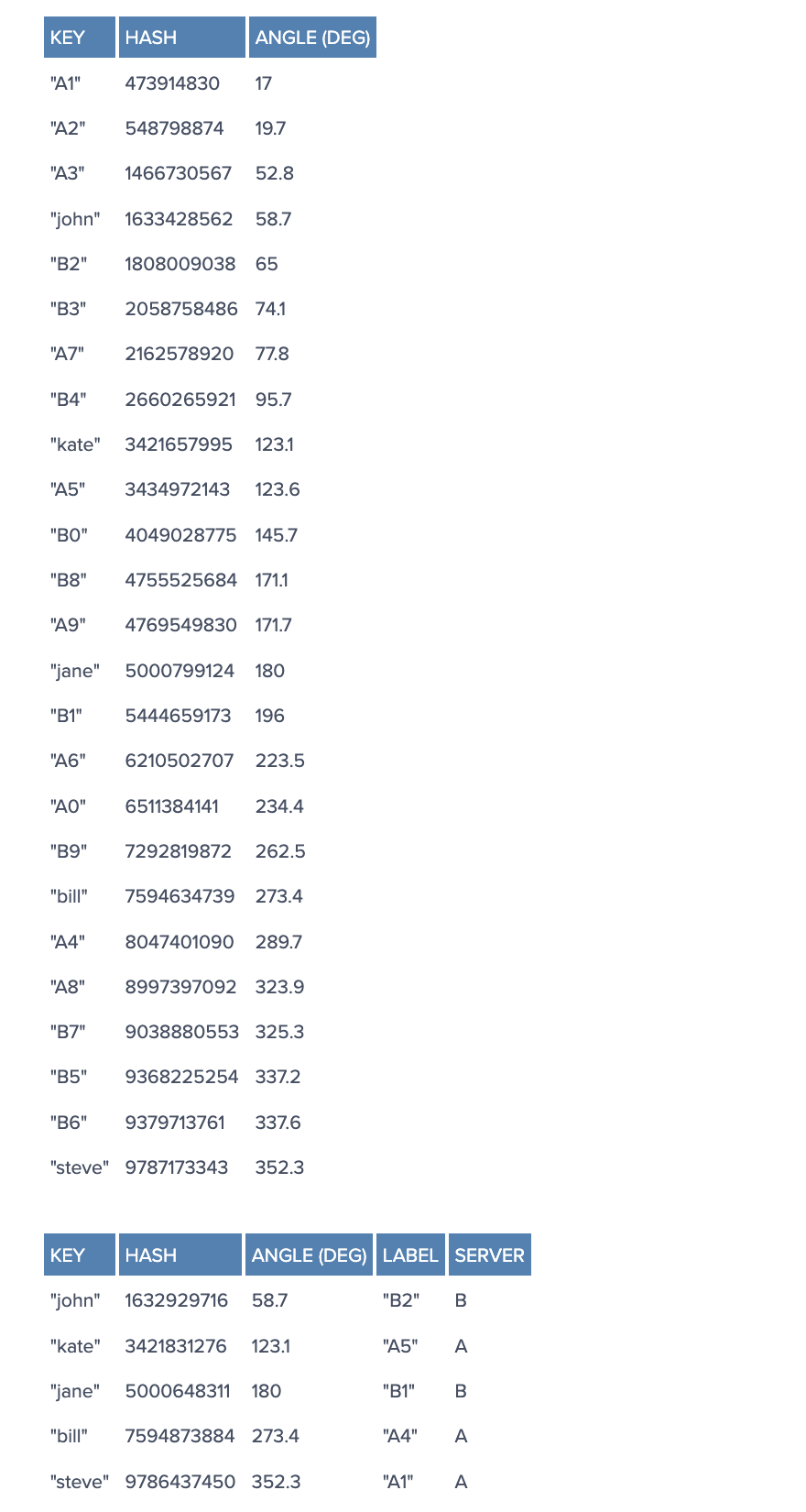

Imagine we mapped the hash output range onto the edge of a circle. That means that the minimum possible hash value, zero, would correspond to an angle of zero, the maximum possible value (some big integer we’ll call INT_MAX) would correspond to an angle of 2𝝅 radians (or 360 degrees), and all other hash values would linearly fit somewhere in between. So, we could take a key, compute its hash, and find out where it lies on the circle’s edge. Assuming an INT_MAX of 1010 (for example’s sake), the keys from our previous example would look like this:

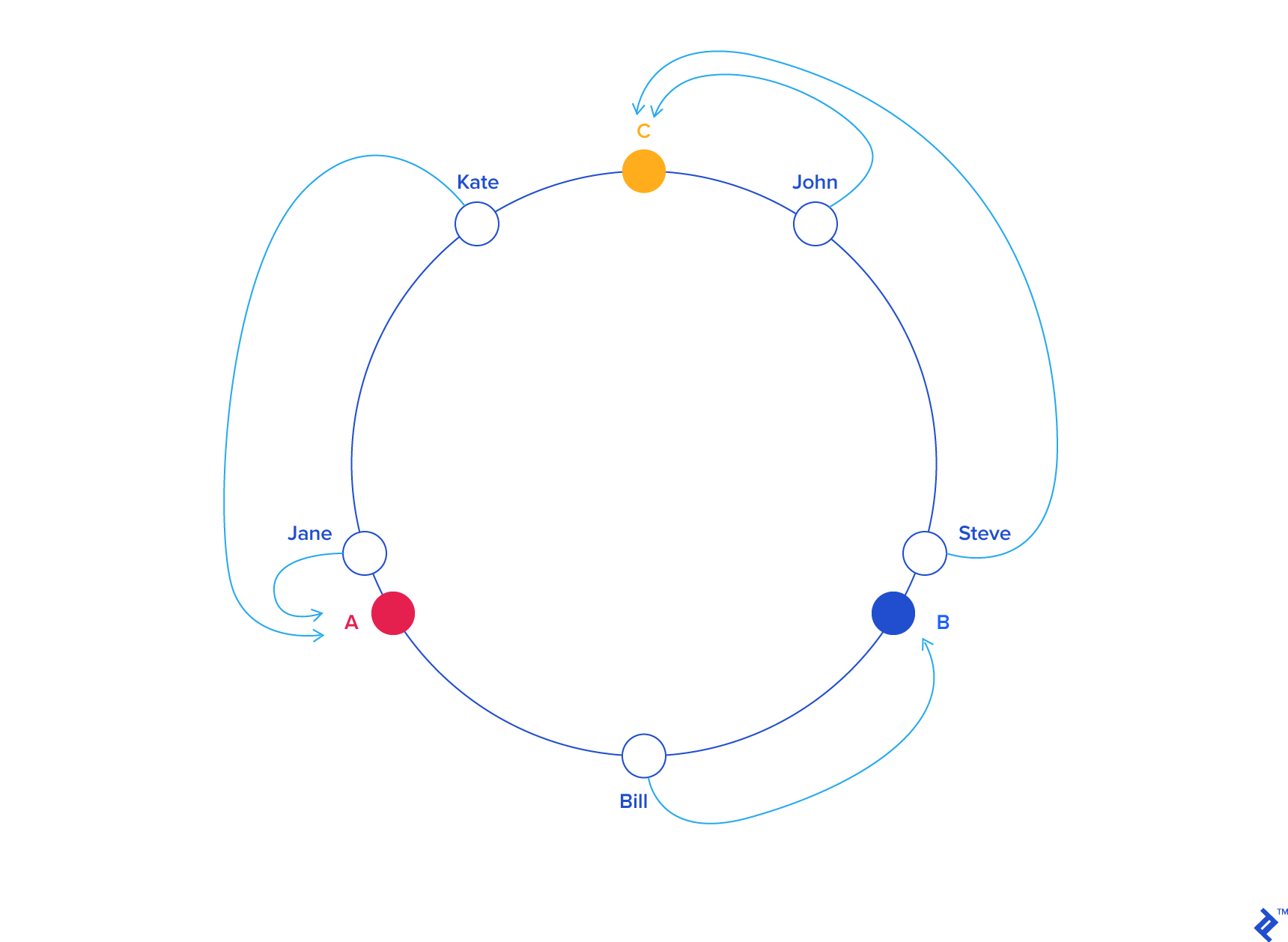

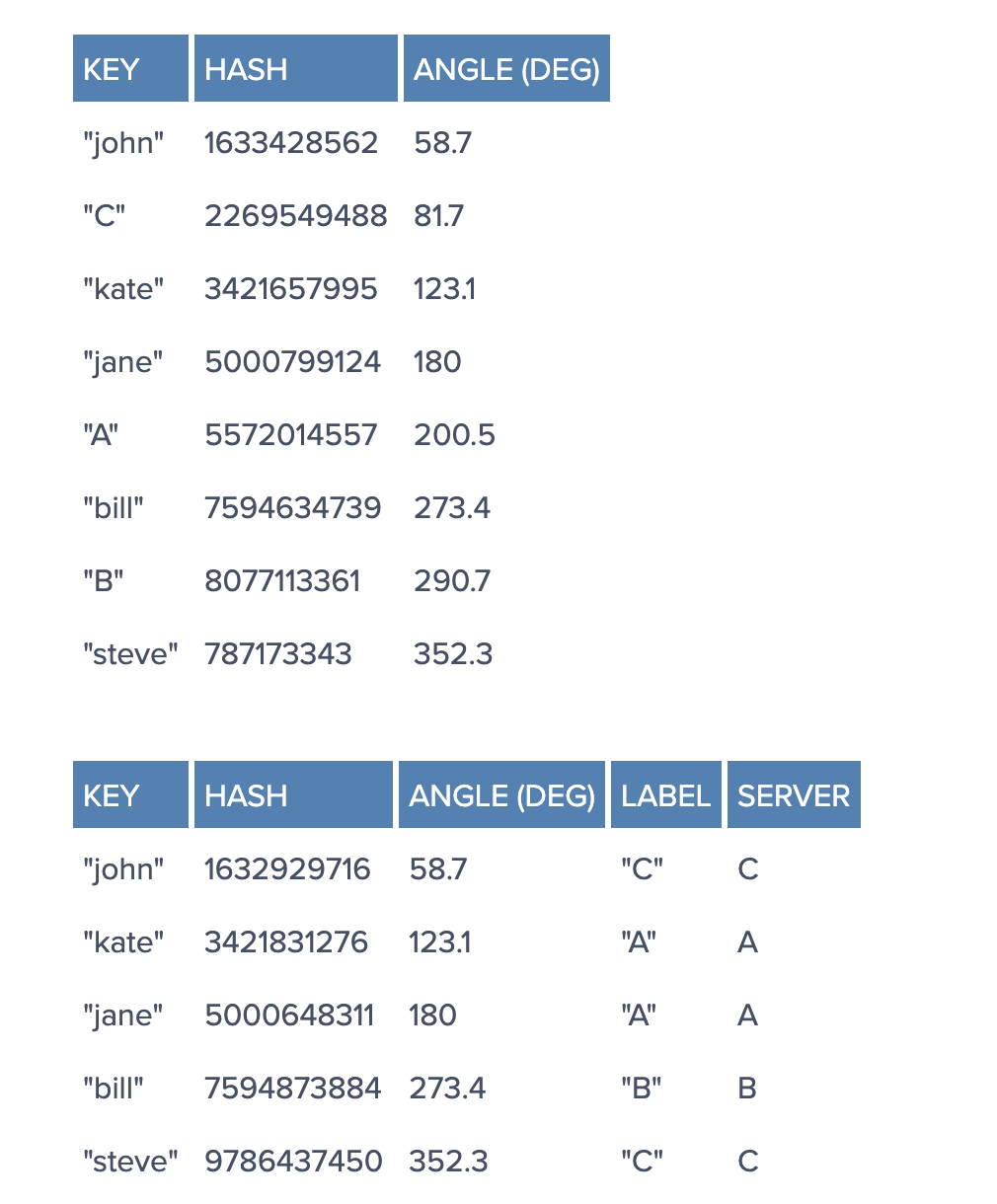

Now imagine we also placed the servers on the edge of the circle, by pseudo-randomly assigning them angles too. This should be done in a repeatable way (or at least in such a way that all clients agree on the servers’ angles). A convenient way of doing this is by hashing the server name (or IP address, or some ID)—as we’d do with any other key—to come up with its angle.

In our example, things might look like this:

Since we have the keys for both the objects and the servers on the same circle, we may define a simple rule to associate the former with the latter: Each object key will belong in the server whose key is closest, in a counterclockwise direction (or clockwise, depending on the conventions used). In other words, to find out which server to ask for a given key, we need to locate the key on the circle and move in the ascending angle direction until we find a server.

In our example:

From a programming perspective, what we would do is keep a sorted list of server values (which could be angles or numbers in any real interval), and walk this list (or use a binary search) to find the first server with a value greater than, or equal to, that of the desired key. If no such value is found, we need to wrap around, taking the first one from the list.

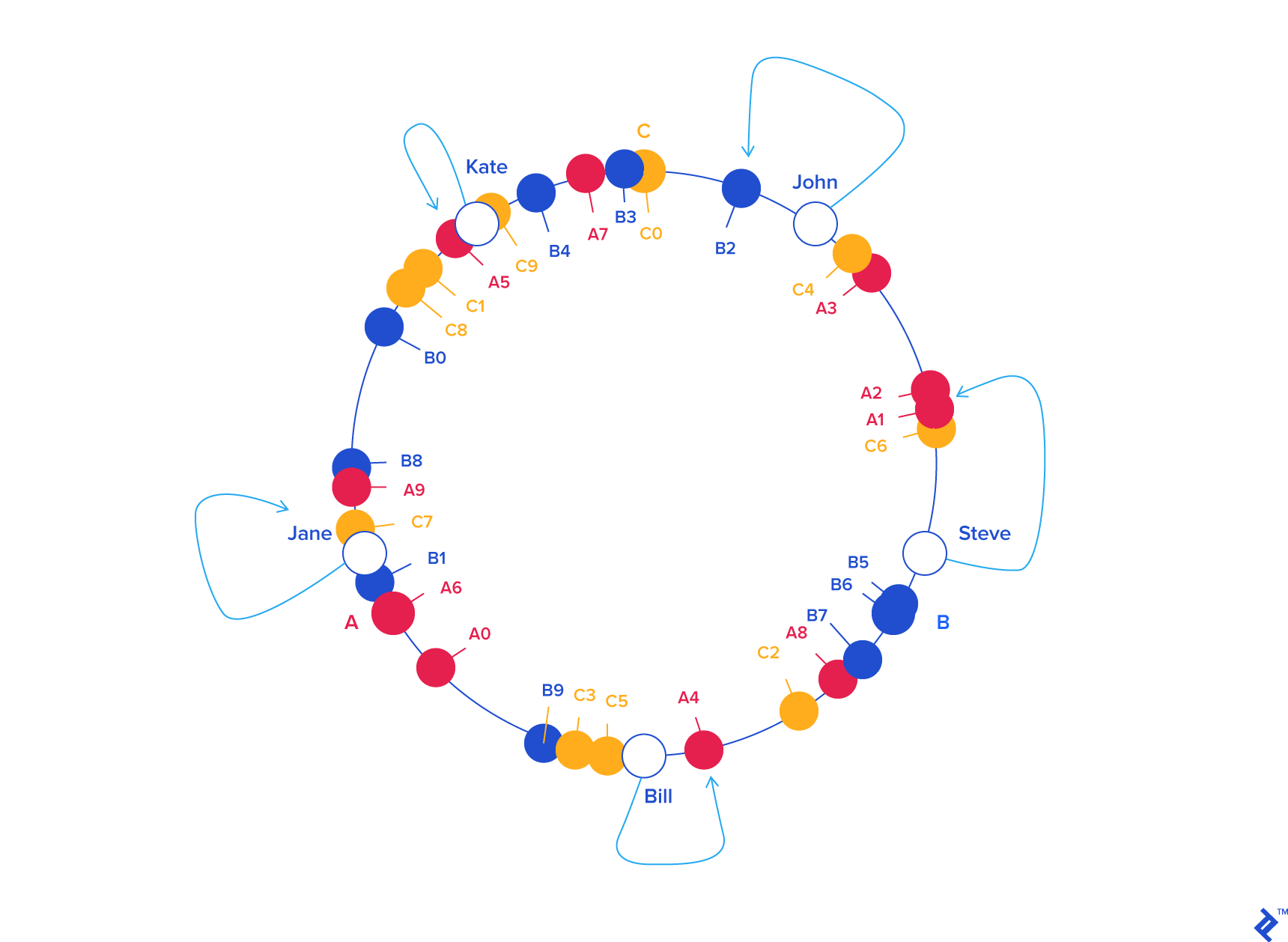

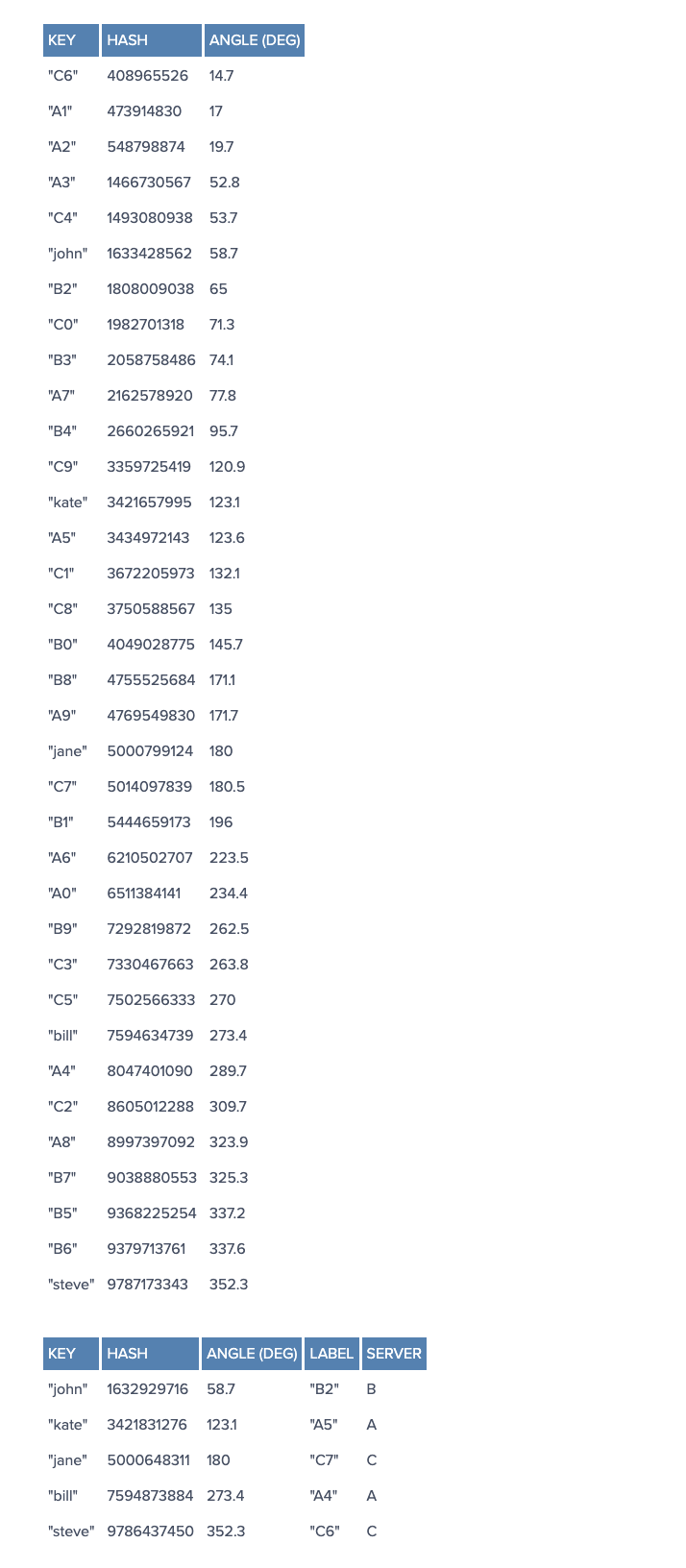

To ensure object keys are evenly distributed among servers, we need to apply a simple trick (为了让 objects 在 servers 中分布更均匀): To assign not one, but many labels (angles) to each server. So instead of having labels A, B and C, we could have, say, A0 .. A9, B0 .. B9 and C0 .. C9, all interspersed along the circle. The factor by which to increase the number of labels (server keys), known as weight, depends on the situation (and may even be different for each server) to adjust the probability of keys ending up on each. For example, if server B were twice as powerful as the rest, it could be assigned twice as many labels, and as a result, it would end up holding twice as many objects (on average).

For our example we’ll assume all three servers have an equal weight of 10 (this works well for three servers, for 10 to 50 servers, a weight in the range 100 to 500 would work better, and bigger pools may need even higher weights):

So, what’s the benefit of all this circle approach? Imagine server C is removed. To account for this, we must remove labels C0 .. C9 from the circle. This results in the object keys formerly adjacent to the deleted labels now being randomly labeled Ax and Bx, reassigning them to servers A and B.

But what happens with the other object keys, the ones that originally belonged in A and B? Nothing! (非常好的设计,C 的删除,不会影响原本 A 和 B 的数据) That’s the beauty of it: The absence of Cx labels does not affect those keys in any way. So, removing a server results in its object keys being randomly reassigned to the rest of the servers, leaving all other keys untouched (其他 Key 不会受影响):

Something similar happens if, instead of removing a server, we add one (增加 server 的情况). If we wanted to add server D to our example (say, as a replacement for C), we would need to add labels D0 .. D9. The result would be that roughly one-third of the existing keys (all belonging to A or B) would be reassigned to D, and, again, the rest would stay the same:

This is how consistent hashing solves the rehashing problem.

In general, only

k/Nkeys need to beremappedwhenkis the number ofkeysandNis the number ofservers(more specifically, the maximum of the initial and final number of servers).

We observed that when using distributed caching to optimize performance, it may happen that the number of caching servers changes (reasons for this may be a server crashing, or the need to add or remove a server to increase or decrease overall capacity). By using consistent hashing to distribute keys between the servers, we can rest assured that should that happen, the number of keys being rehashed—and therefore, the impact on origin servers—will be minimized, preventing potential downtime or performance issues.

There are clients for several systems, such as

MemcachedandRedis, that include support for consistent hashing out of the box.Alternatively, you can implement the algorithm yourself, in your language of choice, and that should be relatively easy once the concept is understood.

History

The term “consistent hashing” was introduced by David Karger et al. at MIT for use in distributed caching, particularly for the web. This academic paper from 1997 in Symposium on Theory of Computing introduced the term “consistent hashing” as a way of distributing requests among a changing population of web servers.

Each slot is then represented by a server in a distributed system or cluster. The addition of a server and the removal of a server (during scalability or outage) requires only num_keys / num_slots items to be re-shuffled when the number of slots (i.e. servers) change.

The authors mention linear hashing and its ability to handle sequential server addition and removal, while consistent hashing allows servers to be added and removed in an arbitrary order.

The paper was later re-purposed to address technical challenge of keeping track of a file in peer-to-peer networks such as a distributed hash table.

Rendezvous hashing, designed in 1996, is a simpler and more general technique. It achieves the goals of consistent hashing using the very different highest random weight (HRW) algorithm.

Basic technique

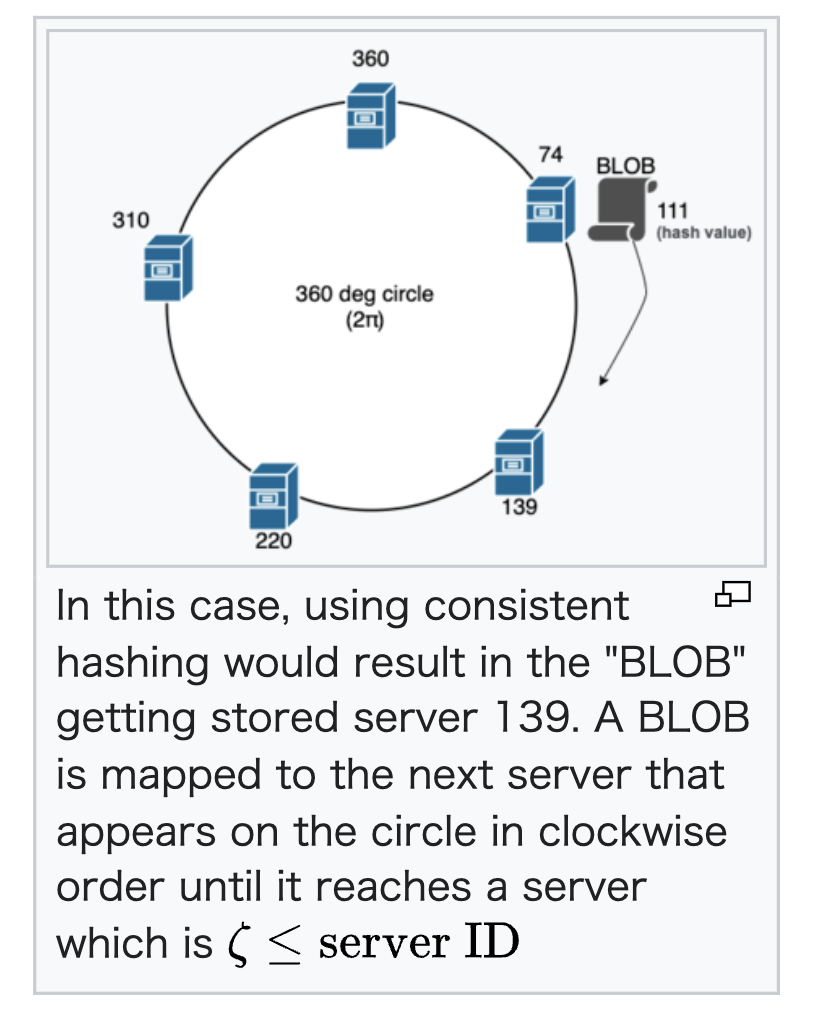

In the problem of load balancing, for example, when a BLOB has to be assigned to one of 𝑛 servers on a cluster, a standard hash function could be used in such a way that we calculate the hash value for that BLOB, assuming the resultant value of the hash is 𝛽, we perform modular operation with the number of servers (𝑛 in this case) to determine the server in which we can place the BLOB: 𝜁 = 𝛽 % 𝑛; hence the BLOB will be placed in the server whose server ID is successor of 𝜁 in this case. However, when a server is added or removed during outage or scaling (when 𝑛 changes), all the BLOBs in every server should be reassigned and moved due to rehashing, but this operation is expensive.

Consistent hashing was designed to avoid the problem of having to reassign every BLOB when a server is added or removed throughout the cluster. The central idea is to use a hash function that maps both the BLOB and servers to a unit circle, usually 2𝜋 radians.

For example, 𝜁 = Φ % 360 (where Φ is hash of a BLOB or server’s identifier, like IP address or UUID). Each BLOB is then assigned to the next server that appears on the circle in clockwise order. Usually, binary search algorithm or linear search is used to find a “spot” or server to place that particular BLOB in 𝑂(log𝑁) or 𝑂(𝑁) complexities respectively; and in every iteration, which happens in clockwise manner, an operation 𝜁 ≤ Ψ (where Ψ is the value of the server within the cluster) is performed to find the server to place the BLOB.

This provides an even distribution of BLOBs to servers. But, more importantly, if a server fails and is removed from the circle, only the BLOBs that were mapped to the failed server need to be reassigned to the next server in clockwise order. Likewise, if a new server is added, it is added to the unit circle, and only the BLOBs mapped to that server need to be reassigned.

Importantly, when a server is added or removed, the vast majority of the BLOBs maintain their prior server assignments, and the addition of 𝑛th server only causes 1/𝑛 fraction of the BLOBs to relocate.

Although the process of moving BLOBs across cache servers in the cluster depends on the context, commonly, the newly added cache server identifies its “successor” and moves all the BLOBs, whose mapping belongs to this server (i.e. whose hash value is less than that of the new server), from it. However, in the case of web page caches, in most implementations there is no involvement of moving or copying, assuming the cached BLOB is small enough. When a request hits a newly added cache server, a cache miss happens and a request to the actual web server is made and the BLOB is cached locally for future requests. The redundant BLOBs on the previously used cache servers would be removed as per the cache eviction policies.

Comparison with rendezvous hashing and other alternatives

Rendezvous hashing, designed in 1996, is a simpler and more general technique, and permits fully distributed agreement on a set of 𝑘 options out of a possible set of 𝑛 options. It can in fact be shown that consistent hashing is a special case of rendezvous hashing. Because of its simplicity and generality, rendezvous hashing is now being used in place of Consistent Hashing in many applications.

If key values will always increase monotonically, an alternative approach using a hash table with monotonic keys may be more suitable than consistent hashing.

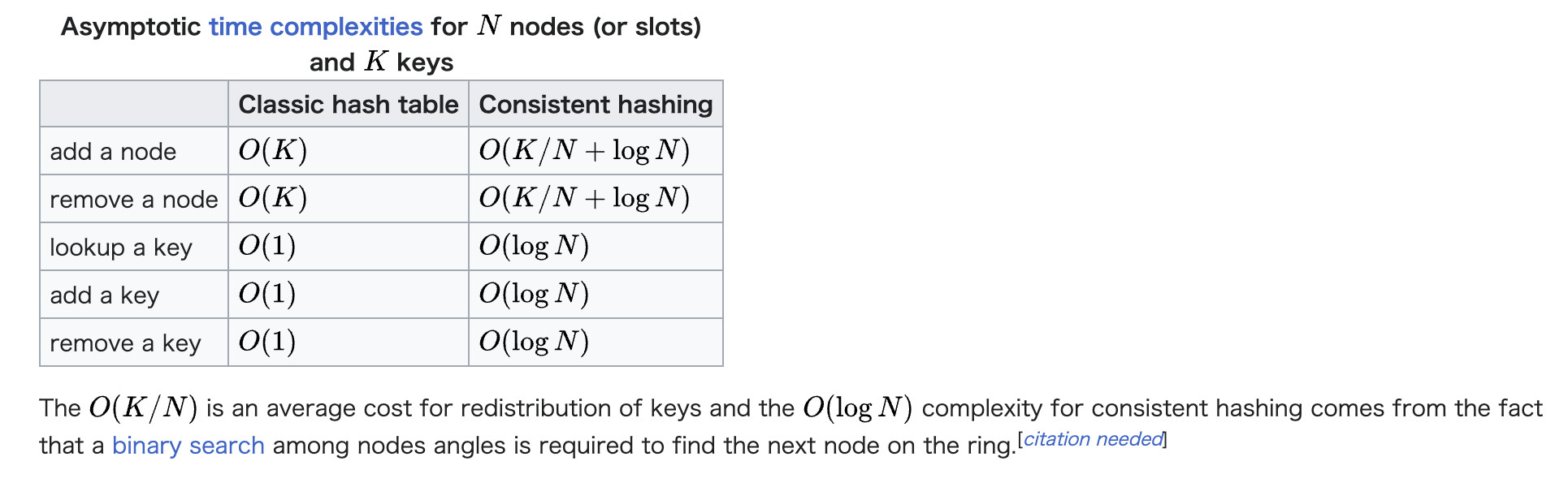

Complexity

gcc 4.8.5 std::hash 实现

参考 libstdc++-v3/libsupc++/hash_bytes.h 实现。

/** @file bits/hash_bytes.h

* This is an internal header file, included by other library headers.

* Do not attempt to use it directly. @headername{functional}

*/

#ifndef _HASH_BYTES_H

#define _HASH_BYTES_H 1

#pragma GCC system_header

#include <bits/c++config.h>

namespace std

{

_GLIBCXX_BEGIN_NAMESPACE_VERSION

// Hash function implementation for the nontrivial specialization.

// All of them are based on a primitive that hashes a pointer to a

// byte array. The actual hash algorithm is not guaranteed to stay

// the same from release to release -- it may be updated or tuned to

// improve hash quality or speed.

size_t

_Hash_bytes(const void* __ptr, size_t __len, size_t __seed);

// A similar hash primitive, using the FNV hash algorithm. This

// algorithm is guaranteed to stay the same from release to release.

// (although it might not produce the same values on different

// machines.)

size_t

_Fnv_hash_bytes(const void* __ptr, size_t __len, size_t __seed);

_GLIBCXX_END_NAMESPACE_VERSION

} // namespace

_Hash_bytes 使用 Murmur hash for 64-bit size_t 的实现,_Fnv_hash_bytes 使用 FNV hash for 64-bit size_t 的实现。

#elif __SIZEOF_SIZE_T__ == 8

// Implementation of Murmur hash for 64-bit size_t.

size_t

_Hash_bytes(const void* ptr, size_t len, size_t seed)

{

static const size_t mul = (((size_t) 0xc6a4a793UL) << 32UL)

+ (size_t) 0x5bd1e995UL;

const char* const buf = static_cast<const char*>(ptr);

// Remove the bytes not divisible by the sizeof(size_t). This

// allows the main loop to process the data as 64-bit integers.

const int len_aligned = len & ~0x7;

const char* const end = buf + len_aligned;

size_t hash = seed ^ (len * mul);

for (const char* p = buf; p != end; p += 8)

{

const size_t data = shift_mix(unaligned_load(p) * mul) * mul;

hash ^= data;

hash *= mul;

}

if ((len & 0x7) != 0)

{

const size_t data = load_bytes(end, len & 0x7);

hash ^= data;

hash *= mul;

}

hash = shift_mix(hash) * mul;

hash = shift_mix(hash);

return hash;

}

// Implementation of FNV hash for 64-bit size_t.

size_t

_Fnv_hash_bytes(const void* ptr, size_t len, size_t hash)

{

const char* cptr = static_cast<const char*>(ptr);

for (; len; --len)

{

hash ^= static_cast<size_t>(*cptr++);

hash *= static_cast<size_t>(1099511628211ULL);

}

return hash;

}

std::hash

template< class Key > // (since C++11)

struct hash;

The unordered associative containers std::unordered_set, std::unordered_multiset, std::unordered_map, std::unordered_multimap use specializations of the template std::hash as the default hash function.

一致性哈希实现

割环法

实现参考:https://github.com/RJ/ketama (C library for consistent hashing, and langauge bindings)

Rendezvous hashing

这个算法比较简单粗暴,没有什么构造环或者复杂的计算过程,它对于一个给定的 Key,对每个节点都通过哈希函数 h() 计算一个权重值 wi,j = h(Keyi, Nodej),然后在所有的权重值中选择最大一个 Max{wi,j}。显而易见,算法挺简单,所需存储空间也很小,但算法的复杂度是 O(n)。

Jump consistent hash

Jump consistent hash 是 Google 于 2014 年发表的论文中提出的一种一致性哈希算法,它占用内存小且速度很快,并且只有大概 5 行代码,比较适合用在分 shard 的分布式存储系统中。其完整的代码如下,其输入是一个 64 位的 Key 及桶的数量,输出是返回这个 Key 被分配到的桶的编号。

int32_t JumpConsistentHash(uint64_t key, int32_t num_buckets) {

int64_t b = -1, j = 0;

while (j < num_buckets) {

b = j;

key = key * 2862933555777941757ULL + 1;

j = (b + 1) * (double(1LL << 31) / double((key >> 33) + 1));

}

return b;

}

Jump consistent hash 有一个比较明显的缺点,它只能在尾部增删节点,而不太好在中间增删。

Maglev hash

Maglev hash 是 Google 于 2016 年发表的一篇论文中提出来的一种新的一致性哈希算法。Maglev hash 的基本思路是建立一张一维的查找表,一个长度为 M 的列表,记录着每个位置所属的节点编号 B0...BN,当需要判断某个 Key 被分配到哪个节点的时候,只需对 Key 计算 hash,然后对 M 取模看所落到的位置属于哪个节点。

查找看上去很简单,问题是如何产生这个查找表。

MurmurHash

MurmurHash is a non-cryptographic hash function suitable for general hash-based lookup. It was created by Austin Appleby in 2008 and is currently hosted on GitHub along with its test suite named SMHasher. It also exists in a number of variants, all of which have been released into the public domain. The name comes from two basic operations, multiply (MU) and rotate (R), used in its inner loop.

Unlike cryptographic hash functions, it is not specifically designed to be difficult to reverse by an adversary, making it unsuitable for cryptographic purposes.

MurmurHash 是一种非加密的哈希函数,适用于基于哈希的一般查找。它是由 Austin Appleby 在 2008 年创建的,并且目前在 GitHub 上托管,连同其名为 SMHasher 的测试套件。它也存在于多种变体中,所有这些变体都已经发布到公共领域。它的名字来源于其内部循环中使用的两个基本操作,乘法(MU)和旋转(R)。

与加密哈希函数不同,MurmurHash 并未特别设计成对抗手方难以逆转,这使得它不适合用于加密目的。

MurmurHash 本身不是一致性哈希算法,而是一个通用的非加密哈希函数。然而,它可以用作一致性哈希算法的底层哈希函数。让我们来区分这两个概念:

- MurmurHash 是一个哈希函数,它将任意长度的输入数据(例如字符串或二进制数据)映射到一个固定大小的哈希值。MurmurHash 的设计目标是快速且在不同输入数据上产生均匀分布的哈希值,以减少哈希冲突。

- 一致性哈希 是一种哈希技术,通常用于分布式系统中,以实现负载均衡和数据分片。一致性哈希算法使用一个哈希函数(如 MurmurHash)将数据映射到一个环形空间,然后将环形空间划分给多个节点。当节点加入或离开系统时,一致性哈希算法确保只需要重新分配很少的数据片段,而不是重新分配所有数据。

因此,MurmurHash 可以作为一致性哈希算法的底层哈希函数,但它本身并不是一致性哈希算法。要实现一致性哈希,需要在 MurmurHash 的基础上构建一个分布式哈希环和相应的数据分配策略。

MurmurHash3

The current version is MurmurHash3, which yields a 32-bit or 128-bit hash value. When using 128-bits, the x86 and x64 versions do not produce the same values, as the algorithms are optimized for their respective platforms. MurmurHash3 was released alongside SMHasher—a hash function test suite.

MementoHash: A Stateful, Minimal Memory, Best Performing Consistent Hash Algorithm

Consistent hashing is used in distributed systems and networking applications to spread data evenly and efficiently across a cluster of nodes. In this paper, we present MementoHash, a novel consistent hashing algorithm that eliminates known limitations of state-of-the-art algorithms while keeping optimal performance and minimal memory usage. We describe the algorithm in detail, provide a pseudo-code implementation, and formally establish its solid theoretical guarantees. To measure the efficacy of MementoHash, we compare its performance, in terms of memory usage and lookup time, to that of state-of-the-art algorithms, namely, AnchorHash, DxHash, and JumpHash. Unlike JumpHash, MementoHash can handle random failures. Moreover, MementoHash does not require fixing the overall capacity of the cluster (as AnchorHash and DxHash do), allowing it to scale indefinitely. The number of removed nodes affects the performance of all the considered algorithms. Therefore, we conduct experiments considering three different scenarios: stable (no removed nodes), one-shot removals (90% of the nodes removed at once), and incremental removals. We report experimental results that averaged a varying number of nodes from ten to one million. Results indicate that our algorithm shows optimal lookup performance and minimal memory usage in its best-case scenario. It behaves better than AnchorHash and DxHash in its average-case scenario and at least as well as those two algorithms in its worst-case scenario. However, the worst-case scenario for MementoHash occurs when more than 70% of the nodes fail, which describes a unlikely scenario. Therefore, MementoHash shows the best performance during the regular life cycle of a cluster.

- 论文 (pdf):https://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.09783

- 实现参考:https://github.com/planecrazyf16/loadbalance-go/blob/edf536a7907c4accde63c3143946295026861093/consistenthash/mementohash.go

对比

对以上四种一致性哈希算法进行对比总结:

| 算法 | 扩容 | 缩容 | 平衡性 | 单调性 | 稳定性 | 时间复杂度 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketama | 好 | 好 | 较好 | 好 | 较好 | O(log vn) |

| Rendezvous | 好 | 好 | 较好 | 好 | 较好 | O(n) |

| Jump consistent hash | 好 | 需要额外处理 | 好 | 好 | 好 | O(ln n) |

| Maglev hash | 较好 | 较好 | 好 | 较好 | 较好 | O(MlogM),最坏 O(M*M) |

一致性哈希的 Q&A

一致性哈希的优点

一致性哈希算法具有以下几个优点:

- 均衡负载:一致性哈希算法能够将数据在节点上均匀分布,避免出现热点数据集中在某些节点上而导致负载不均衡的情况。通过增加虚拟节点的数量,可以进一步增强负载均衡的效果;

- 扩展性:在一致性哈希算法中,当节点数量增加或减少时,只有部分数据需要重新映射,系统能够进行水平扩展更容易,可以增加节点数量以应对更大的负载需求;

- 减少数据迁移:相比传统的哈希算法,一致性哈希算法在节点增减时需要重新映射的数据量较少,可以大幅降低数据迁移的开销,减少系统的不稳定性和延迟;

- 容错性:一致性哈希算法在节点故障时能够保持较好的容错性。当某个节点失效时,只有存储在该节点上的数据需要重新映射,这使得系统能够更好地应对节点故障,提高系统的可用性和稳定性;

- 简化管理:由于一致性哈希算法中节点的加入和离开对数据分片的影响较小,系统管理员进行节点的动态管理更加方便。节点的扩容和缩容操作对整个系统的影响相对较小,简化了系统的管理和维护过程。

一致性哈希如何实现负载均衡

一致性哈希算法实现负载均衡的关键在于将数据均匀地分布到不同的节点上。以下是一致性哈希算法如何实现负载均衡的基本过程:

- 节点映射:将每个物理节点通过哈希函数映射到一个哈希环上的位置,可以使用节点的唯一标识符或节点的 IP 地址等作为输入进行哈希计算。哈希函数的选择应该具有良好的分布性,以确保节点在哈希环上均匀分布;

- 数据映射:将要存储的数据通过相同的哈希函数映射到哈希环上的一个位置。之后根据数据的哈希值,顺时针查找离该位置最近的节点,将数据存储在该节点上;

- 数据查找:当需要查找数据时,将要查找的数据通过哈希函数映射到哈希环上的一个位置。之后根据数据的哈希值,顺时针查找离该位置最近的节点,从该节点上获取所需的数据;

- 节点增减:当有新的节点加入系统或节点离开系统时,只需要重新映射受影响的数据。对于新增节点,可以在哈希环上添加虚拟节点,通过重新映射一部分数据到新增节点上实现负载均衡。对于离开节点,可以将该节点上的数据重新映射到其顺时针下一个节点上。

需要注意的是,一致性哈希算法并不能完全消除负载不均衡的情况,但它能够在节点数量较大时提供较好的负载均衡效果。

一致性哈希如何解决节点增加或删除的问题

一致性哈希是一种解决节点增加或删除问题的算法。它通过将节点和数据映射到一个统一的哈希环上,构建了一个虚拟的圆环结构。当节点增加或删除时,只会影响到相邻节点之间的数据映射,而不会影响到整个哈希环。当新增节点加入时,它会被插入到环中的适当位置,且只会影响到其后的节点。同样,当节点删除时,它会被从环中移除,且只会影响到其后的节点。这种方式使得节点的增加或删除对已分配的数据影响最小化,大部分数据仍然可以保持映射到原来的节点,也让一致性哈希算法在动态环境下具有良好的扩展性和容错性,能够适应节点的动态变化,保持负载均衡,并减少对整个系统的影响,提高了系统的可用性和稳定性。

一致性哈希如何处理节点故障

- 节点故障检测。一致性哈希算法通常通过心跳检测或其他机制来监测节点的健康状态。当某个节点故障或无法响应时,算法会将其标记为不可用状态。

- 数据映射和访问。当需要存储数据或查找数据时,算法会根据数据的哈希值在哈希环上找到离该位置最近的可用节点。如果目标节点不可用,算法会继续顺时针查找下一个可用节点,直到找到一个可用节点为止,这样可以确保数据能够被正确地定位并访问。

- 节点故障后的数据迁移。当节点故障时,该节点上的数据需要重新映射到其他可用节点。只有与故障节点相关的数据需要重新映射,其他节点上的数据保持不变,这样可以最小化数据迁移的开销。

- 虚拟节点的作用。一致性哈希算法中的虚拟节点可以在节点故障时起到关键作用。虚拟节点的存在使得数据能够均匀地映射到多个物理节点,当一个物理节点故障时,其上的虚拟节点会被合并到其他物理节点上,保持数据的连续性和均衡性。

一致性哈希如何保证数据的一致性

一致性哈希算法本身并不直接保证数据的一致性,而是一种用于负载均衡的分布式算法。不过一致性哈希可以采取其他措施来确保数据一致性。以下是一些常见的方法:

- 复制数据:通过在多个节点上复制数据副本,可以提高数据的可靠性和一致性。一致性哈希算法可以确定数据存储在哪个节点上,而复制策略可以将数据复制到其他节点上。这样,在节点故障或数据损坏时,可以从其他节点获取数据的副本,确保数据的可用性和一致性;

- 数据同步:当数据被更新时,需要确保在所有副本之间进行同步。常见的方法包括主从复制、多主复制或基于共享日志的复制。这些技术可以保证在数据更新时,所有相关节点上的数据保持一致;

- 一致性协议:一致性哈希算法可以与一致性协议(如 Paxos、Raft 等)结合使用,以确保数据一致性。这些协议提供了一致性保证机制,可以确保在节点故障、网络分区等情况下,仍然能够达到数据一致性;

- 数据版本控制:使用适当的数据版本控制机制,可以跟踪和管理数据的不同版本,确保数据的一致性。例如,使用向量时钟 (vector clocks) 或时间戳 (timestamps) 来标记数据的版本,并在更新时进行适当的冲突解决;

需要注意的是,数据的一致性是一个复杂的问题,一致性哈希算法本身并不能提供完全的一致性保证。在设计和实现分布式系统时,需要综合考虑一致性哈希算法以及其他的一致性机制和技术,以满足特定的一致性要求和应用场景。

常见的一致性哈希应用场景有哪些

一致性哈希算法在分布式系统中具有广泛的应用场景,以下是一些常见的应用场景:

- 缓存系统:一致性哈希算法被广泛用于分布式缓存系统,例如分布式内存缓存(如 Memcached)或分布式键值存储(如 Redis)。通过将数据根据哈希值映射到缓存节点,可以实现负载均衡和数据分布的优化;

- 分布式文件系统:一致性哈希算法可用于分布式文件系统中的数据分片和数据块的分配。它可以将文件块映射到不同的存储节点上,实现数据的分散存储和高吞吐量的访问;

- 负载均衡器:一致性哈希算法可以用于负载均衡器(如反向代理或负载均衡服务器)的请求路由。它可以将请求路由到后端服务器集群中的不同节点,实现负载均衡和故障恢复;

- 分布式数据库:一致性哈希算法可以用于分布式数据库系统中的数据分片和数据复制。它可以将数据均匀地分布在多个节点,并确保数据的可用性和一致性;

- 分布式哈希表:一致性哈希算法可以用于实现分布式哈希表,使得数据可以分布在多个节点上,并提供高效的键值查找和存储;

- 分布式消息队列:一致性哈希算法可用于分布式消息队列中的消息路由和分发。它可以确保消息被正确地路由到相应的消费者节点上,实现高吞吐量和可靠的消息传递。

Refer

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consistent_hashing

- Rendezvous hashing

- A Guide to Consistent Hashing (好文)

- https://www.amazonaws.cn/knowledge/what-is-consistent-hashing

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MurmurHash

- https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/hash

- https://github.com/gcc-mirror/gcc/tags

- https://github.com/gcc-mirror/gcc/blob/releases/gcc-12.1.0/libstdc++-v3/include/bits/functional_hash.h

- https://github.com/gcc-mirror/gcc/blob/releases/gcc-12.1.0/libstdc++-v3/libsupc++/hash_bytes.cc