Modern CMake in Action

- Why use a Modern CMake?

- More Modern CMake - Working with CMake 3.12 and later

- What is CMake

- A(VERY) BRIEF HISTORY OF CMake

- Build-requirements of a target

- Usage-requirements of a target

- Traditional CMake? Modern CMake? What’s the difference?

- Modern CMake setting build-requirements VS setting usage-requirements

- Modern CMake Demo

- Object libraries some peculiarities

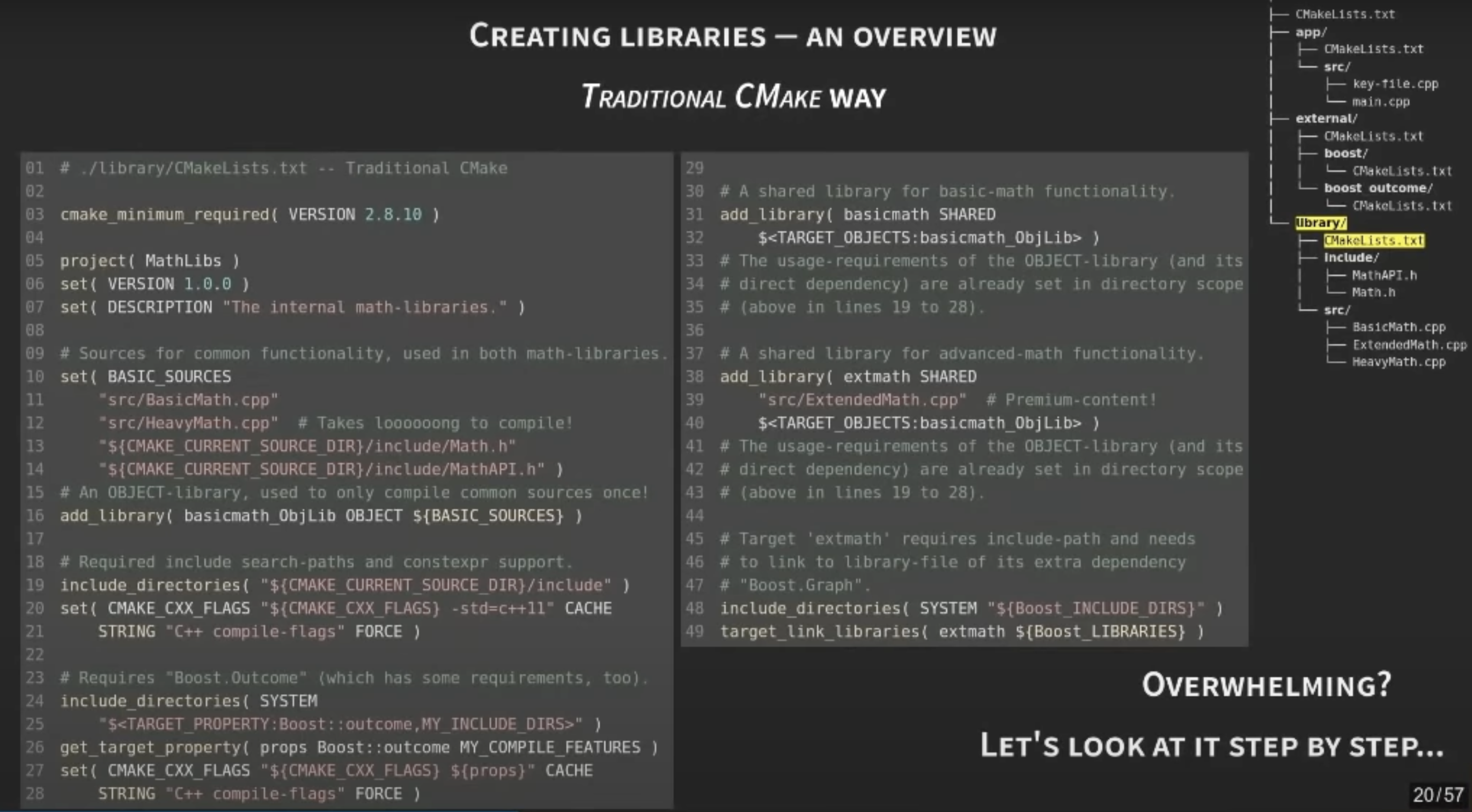

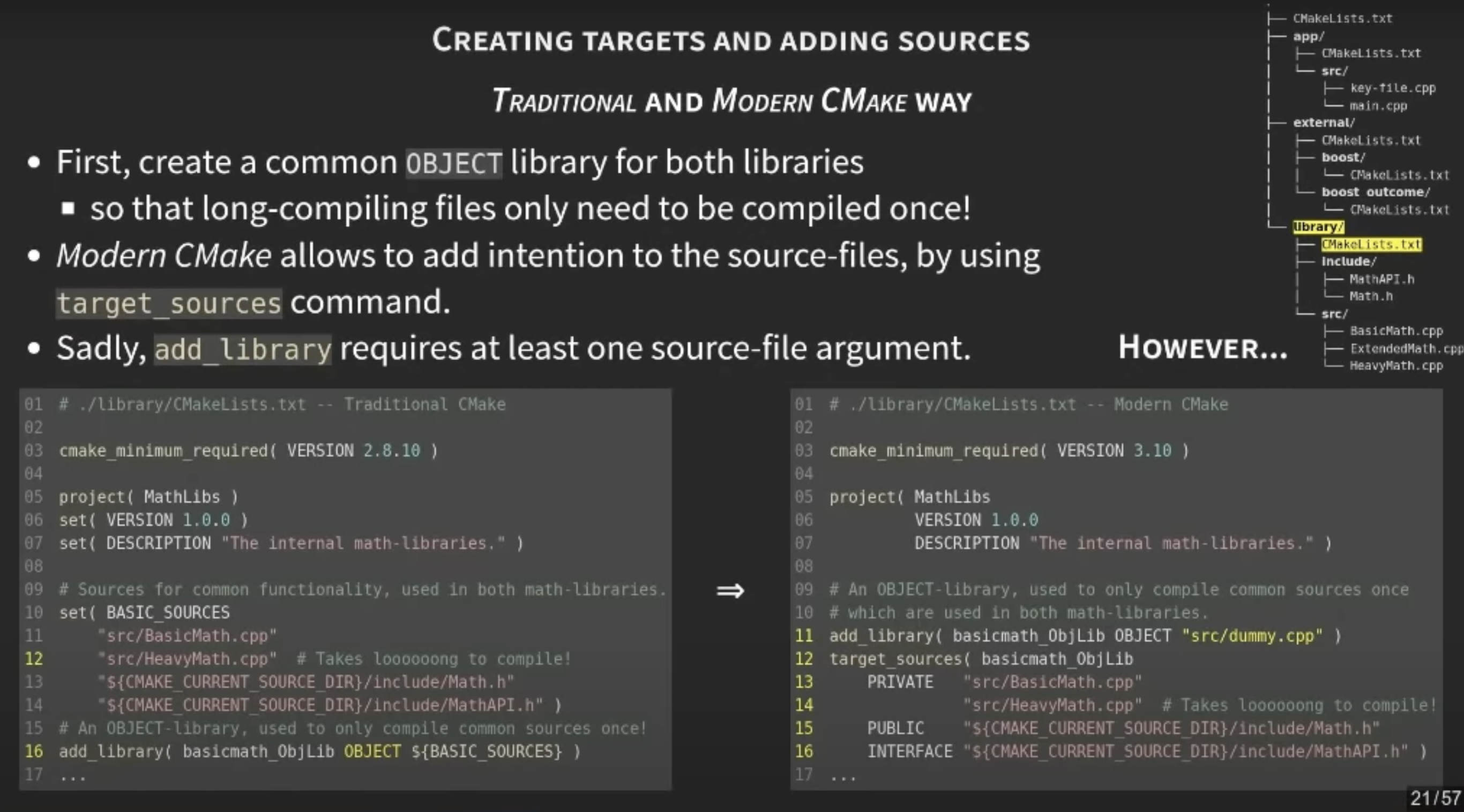

- Creating Libraries

- Refer

I’m talking about Modern CMake. CMake 3.4+, maybe even CMake 3.24+! It’s clean, powerful, and elegant, so you can spend most of your time coding, not adding lines to an unreadable, unmaintainable Make (Or CMake 2) file. And CMake 3.11+ is supposed to be significantly faster, as well!

Why use a Modern CMake?

Around CMake 2.6-2.8, CMake started taking over. It was in most of the package managers for Linux OS’s, and was being used in lots of packages.

Then Python 3 came out.

I know, this should have nothing whatsoever to do with CMake.

But it had a 3. And it followed 2. And it was a hard, ugly, transition that is still ongoing in some places, even today.

I believe that CMake 3 had the bad luck to follow Python 3.1 Even though every version of CMake is insanely backward compatible, the 3 series was treated as if it were something new. And so, you’ll find OSs like CentOS7 with GCC 4.8, with almost-complete C++14 support, and CMake 2.8, which came out years before C++11.

You really should at least use a version of CMake that came out after your compiler, since it needs to know compiler flags, etc, for that version. And, since CMake will dumb itself down to the minimum required version in your CMake file, installing a new CMake, even system wide, is pretty safe. You should at least install it locally. It’s easy (1-2 lines in many cases), and you’ll find that 5 minutes of work will save you hundreds of lines and hours of CMakeLists.txt writing, and will be much easier to maintain in the long run.

This book tries to solve the problem of the poor examples and best practices that you’ll find proliferating the web.

More Modern CMake - Working with CMake 3.12 and later

What is CMake

- CMake is a build-system generator

- Not a build-system, though!

- generates input files for build-generators.

- Supports: Make, Ninja, Visual Studio, Xcode, …

- It is cross-platform.

- Supports running on: Linux, Windows, OSX, …

- Supports building cross-platform, too.

- If the compiler supports that.

- Supports generating build-systems for multiple languages.

- C/C++, FORTRAN, C#, CUDA, …

A(VERY) BRIEF HISTORY OF CMake

- CMake started around 1999/2000.

- Not modern.

-

-> Traditional CMake

- CMake is “modern” since version 3.0 (around 2014)

- New concept: “everything is a (self-contained) target”.

-

-> Modern CMake

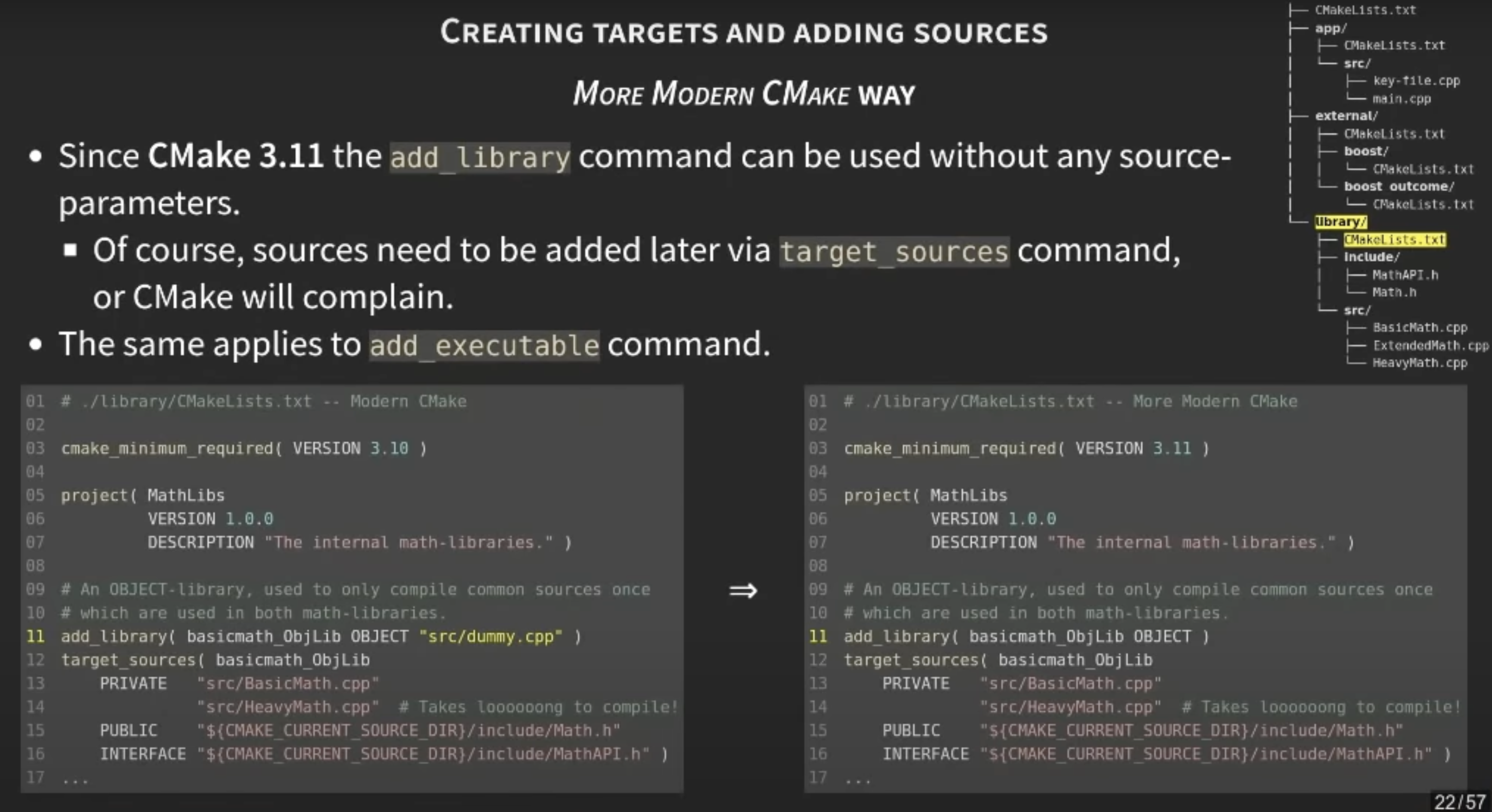

- CMake 3.11 was released (March 2018)

- Unifies several commands.

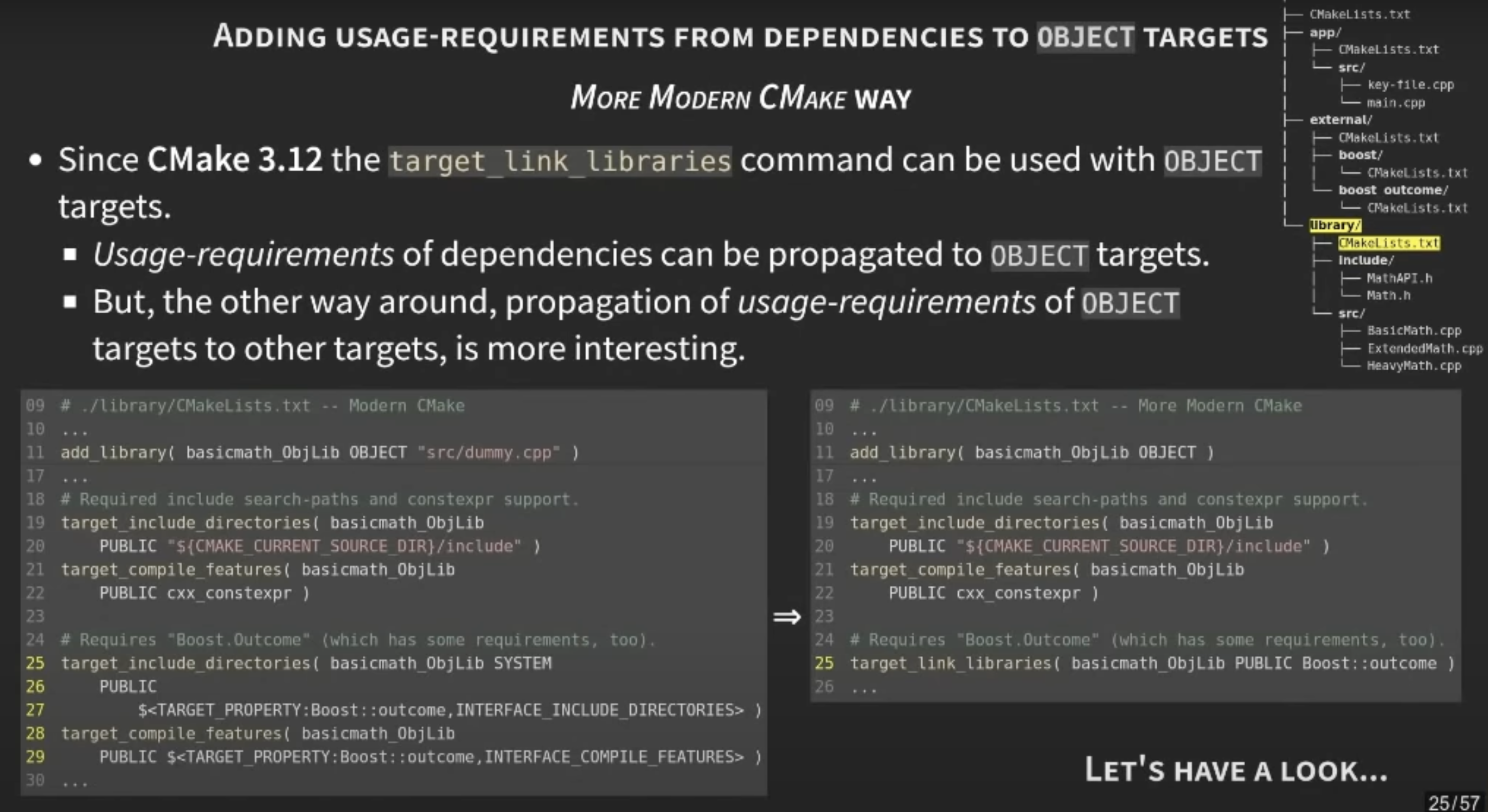

- CMake 3.12 was released (July 2018)

- Some of the big left-out tasks of Modern CMake were completed.

- -> More Modern CMake

Build-requirements of a target

“Everything that is needed to (successfully) build that target.”

- source-files

- include search-paths

- pre-processor macros

- link-dependencies

- compiler/linker-options

- compiler/linker-features

- (e.g. support for a C++ standard)

Usage-requirements of a target

“Everything that is needed to (successfully) use that target.”

“As a dependency of another target.”

- source-files

- (but normally not)

- include search-paths

- per-processor macros

- link-dependencies

- compiler/linker-options

- compiler/linker-features

- (e.g. support for a C++ standard)

Traditional CMake? Modern CMake? What’s the difference?

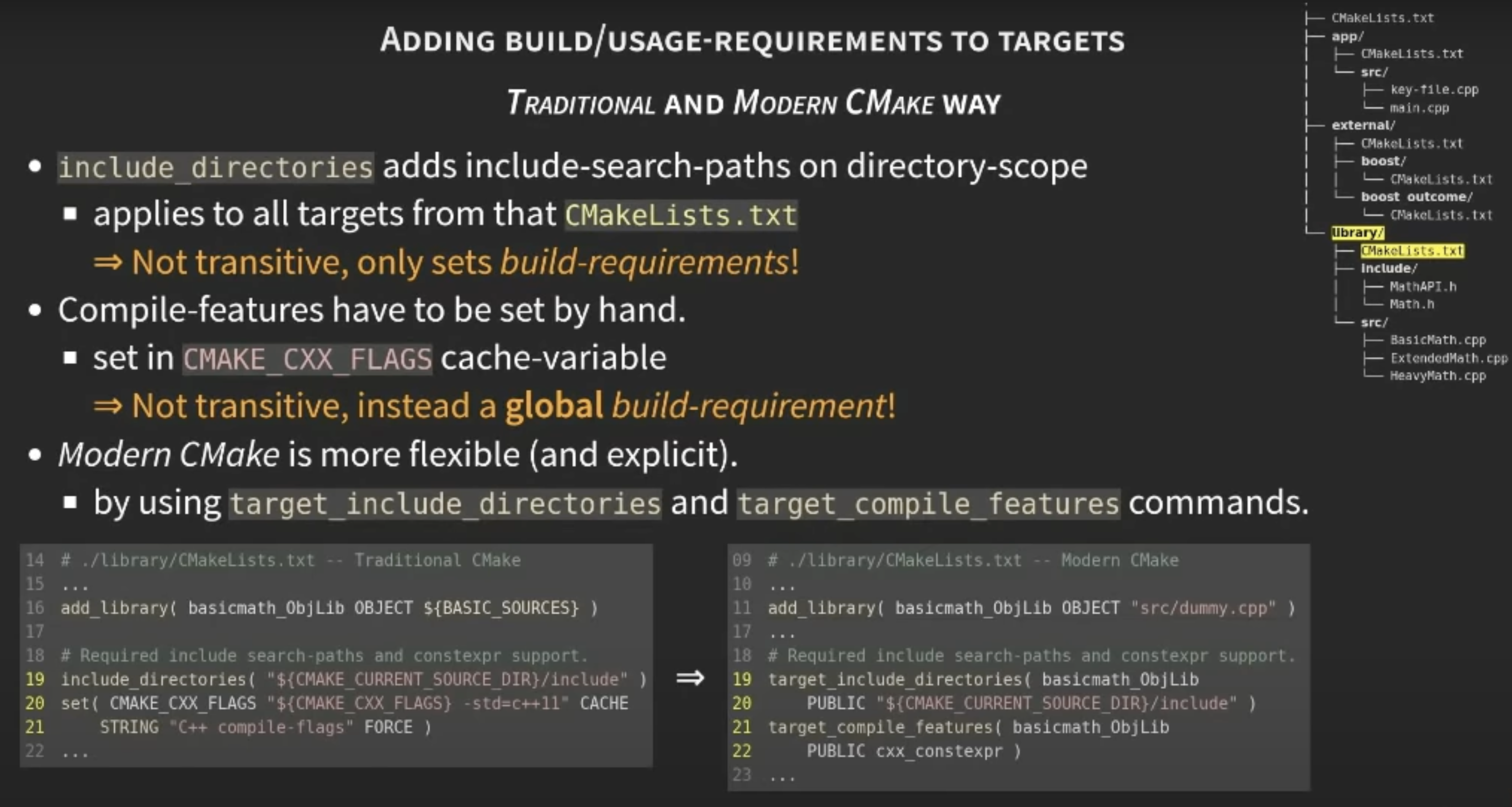

Modern CMake setting build-requirements VS setting usage-requirements

# Adding build-requirements

target_include_directories( <target> PRIVATE <include-search-dir>... )

target_compile_definitions( <target> PRIVATE <macro-definitions>... )

target_compile_options( <target> PRIVATE <compiler-option>... )

target_compile_features( <target> PRIVATE <feature>... )

target_sources( <target> PRIVATE <source-file>... )

target_link_libraries( <target> PRIVATE <dependency>... )

target_link_options( <target> PRIVATE <linker-option>... )

target_link_directories( <target> PRIVATE <linker-search-dir>... )

# Adding usage-requirements

target_include_directories( <target> INTERFACE <include-search-dir>... )

target_compile_definitions( <target> INTERFACE <macro-definitions>... )

target_compile_options( <target> INTERFACE <compiler-option>... )

target_compile_features( <target> INTERFACE <feature>... )

target_sources( <target> INTERFACE <source-file>... )

target_link_libraries( <target> INTERFACE <dependency>... )

target_link_options( <target> INTERFACE <linker-option>... )

target_link_directories( <target> INTERFACE <linker-search-dir>... )

# Adding build and usage-requirements

target_include_directories( <target> PUBLIC <include-search-dir>... )

target_compile_definitions( <target> PUBLIC <macro-definitions>... )

target_compile_options( <target> PUBLIC <compiler-option>... )

target_compile_features( <target> PUBLIC <feature>... )

target_sources( <target> PUBLIC <source-file>... )

target_link_libraries( <target> PUBLIC <dependency>... )

target_link_options( <target> PUBLIC <linker-option>... )

target_link_directories( <target> PUBLIC <linker-search-dir>... )

Warning: Although

target_link_directoriescan be used without these keywords, you should never forget to use these keywords in Modern CMake!

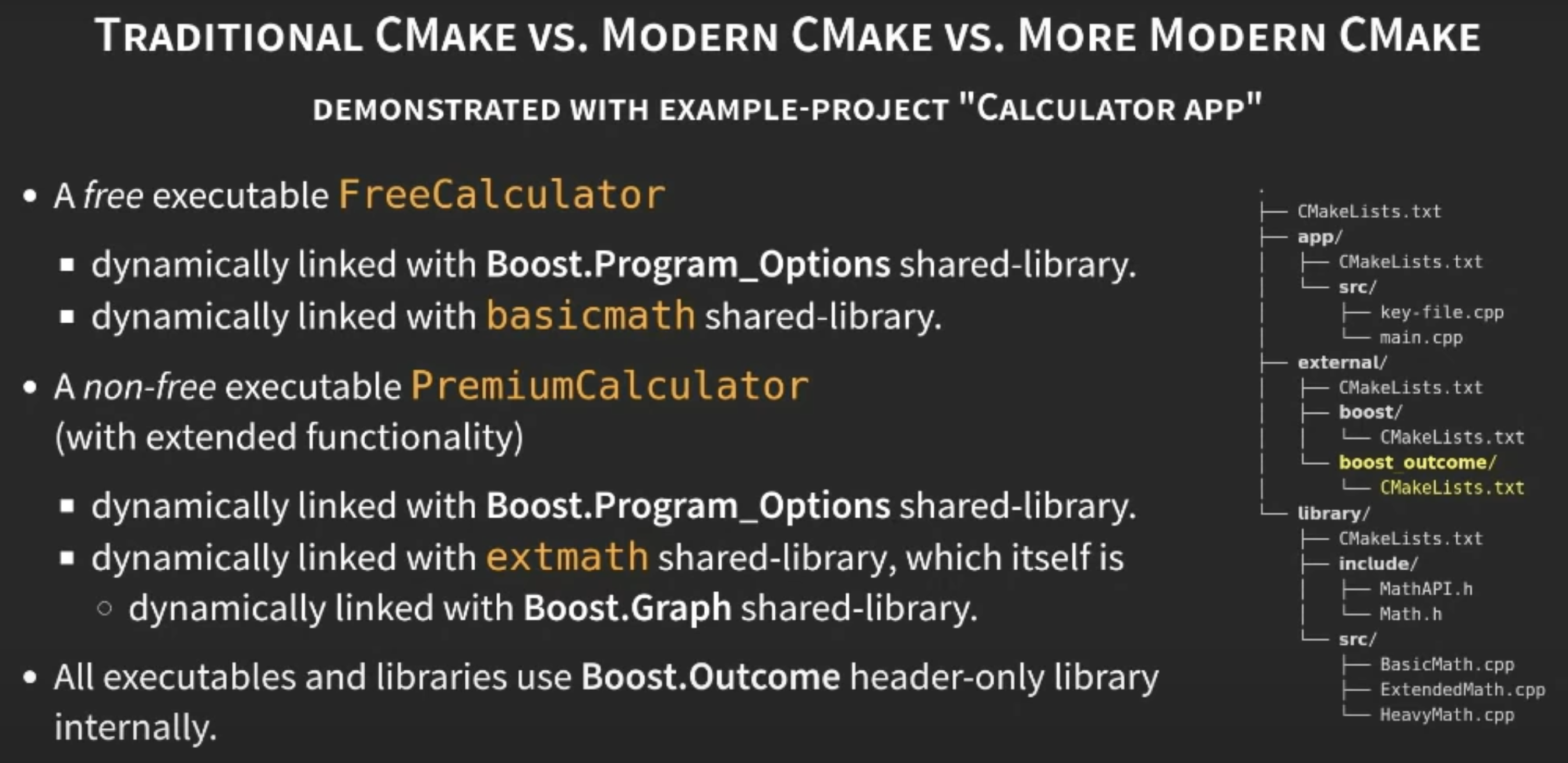

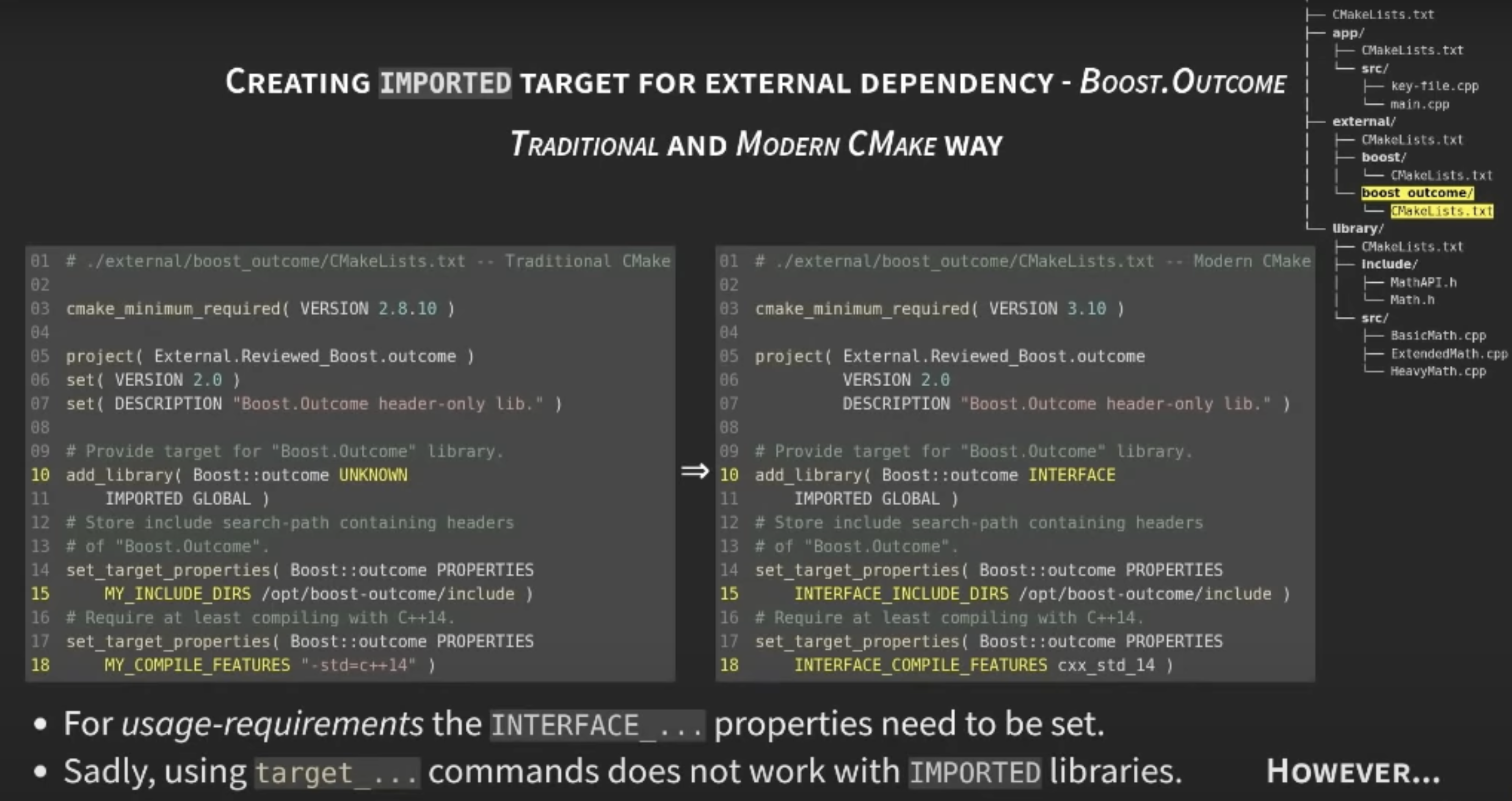

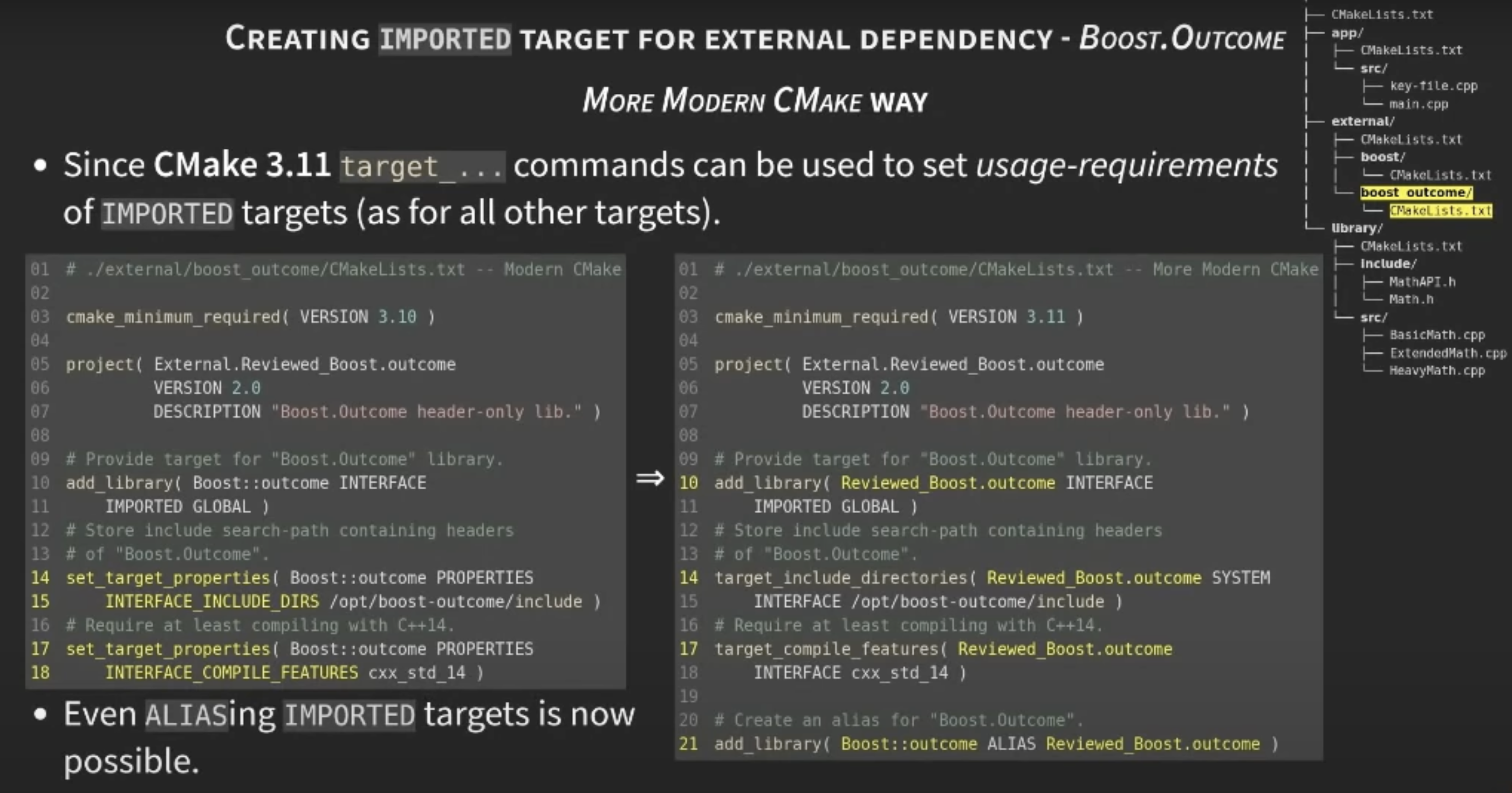

Modern CMake Demo

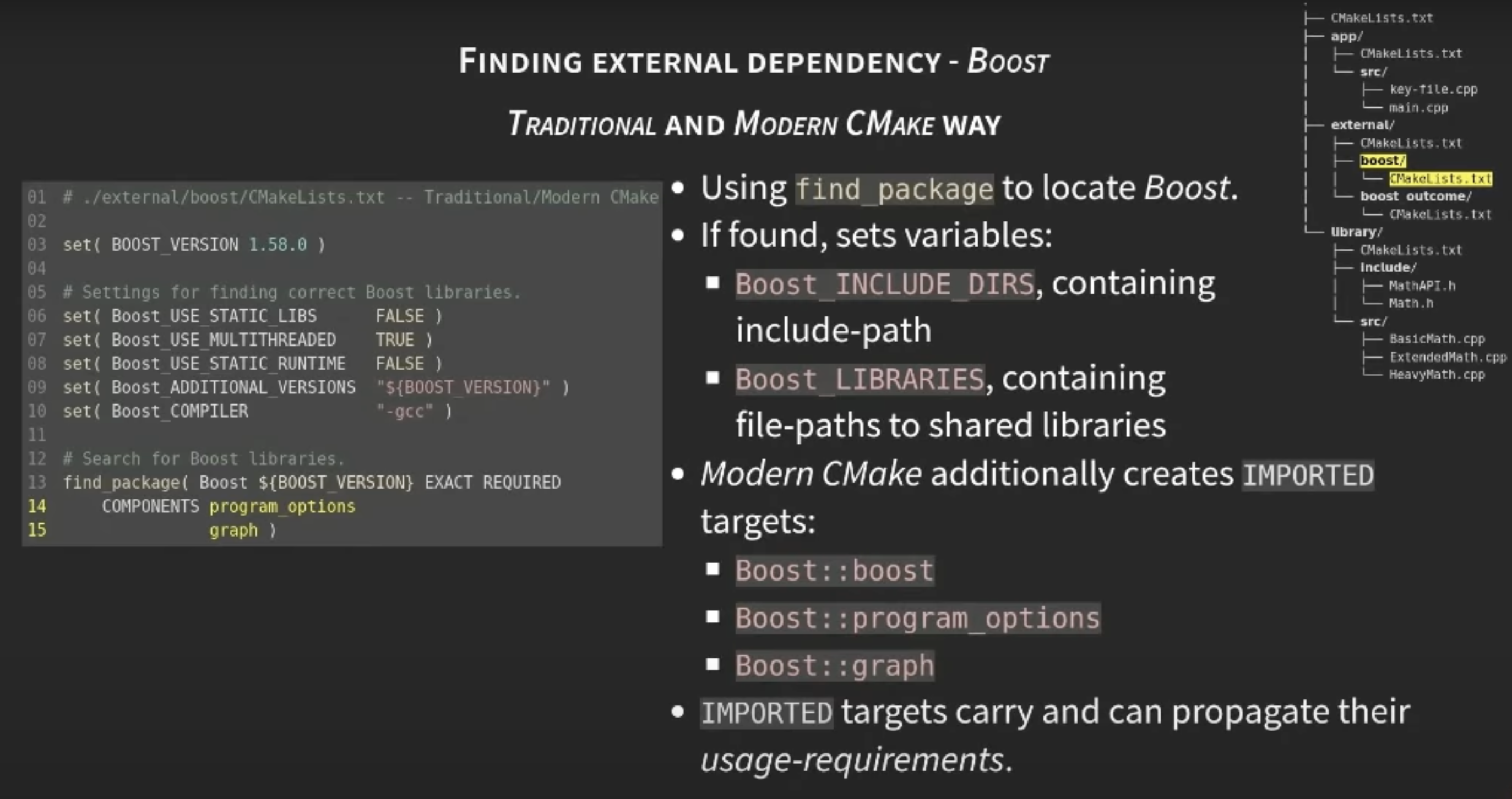

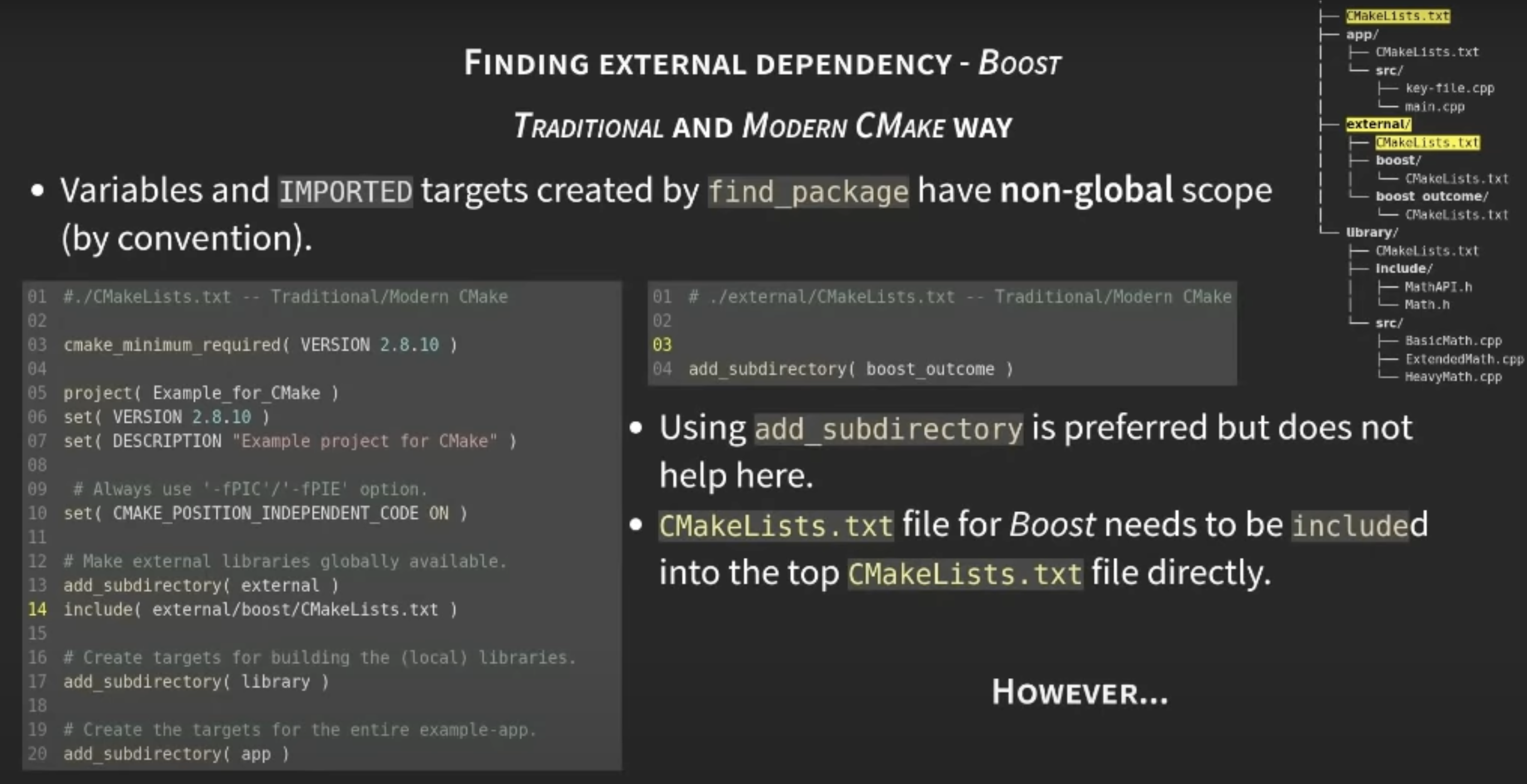

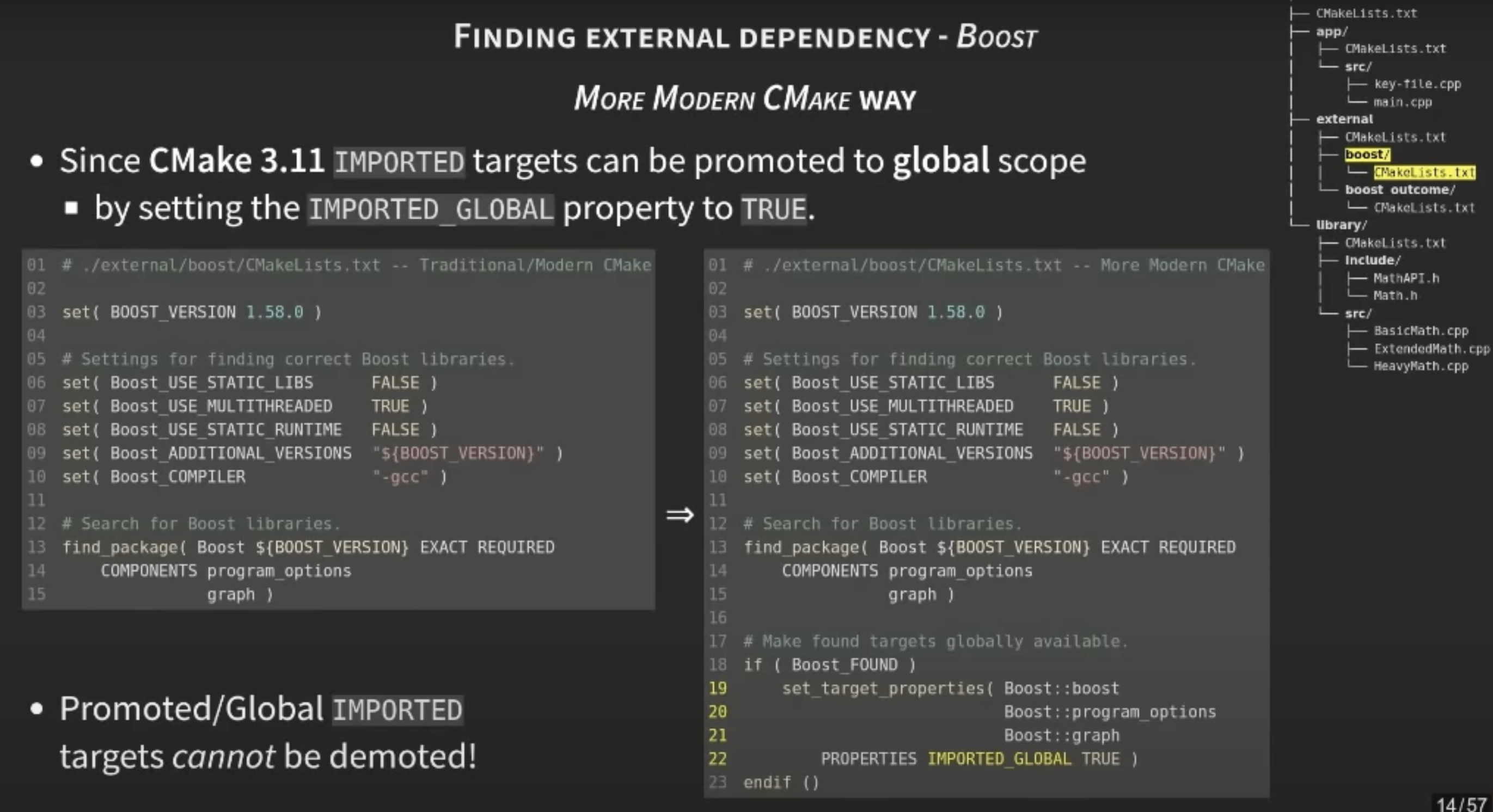

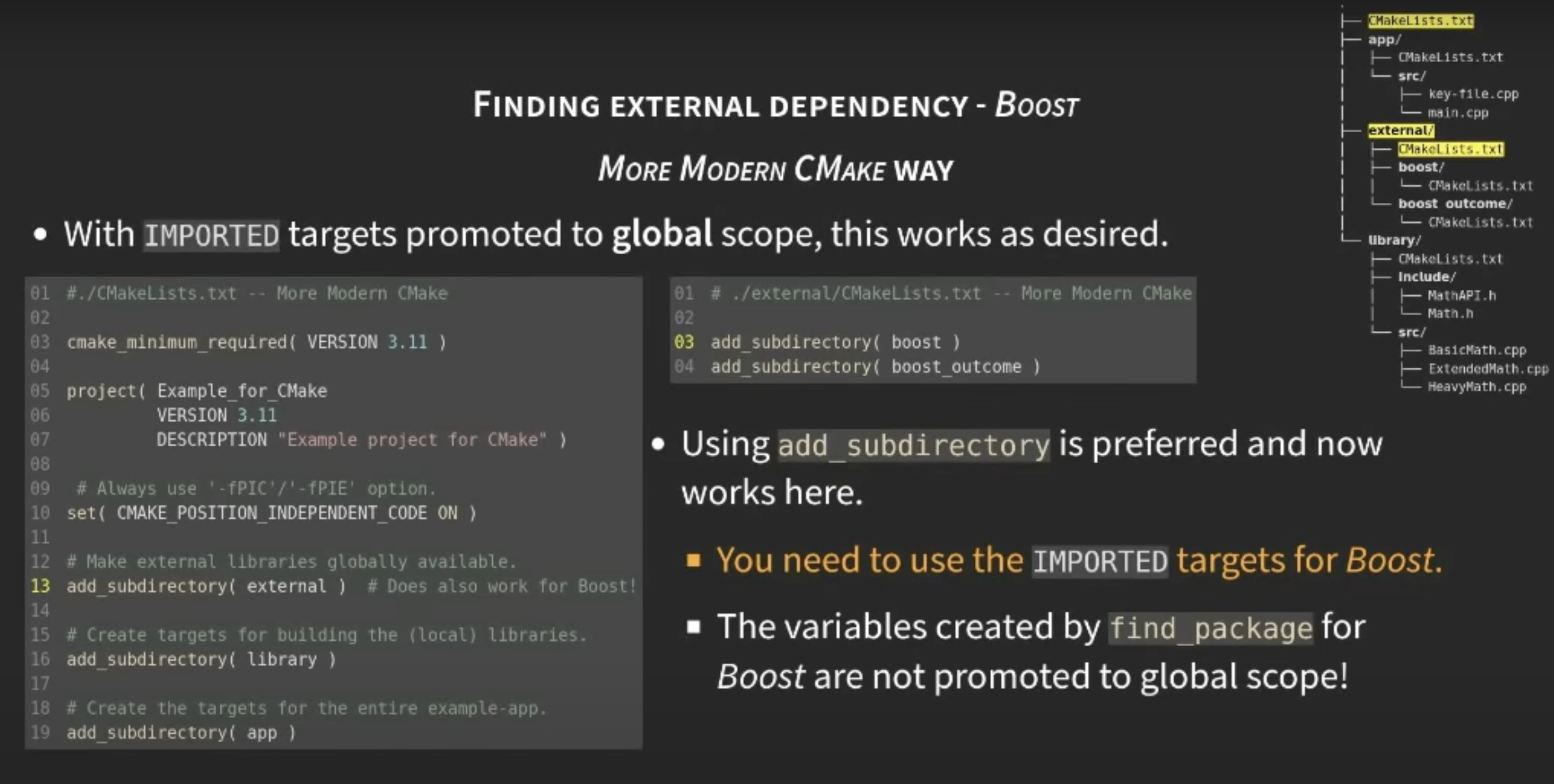

First, finding external dependency Boost

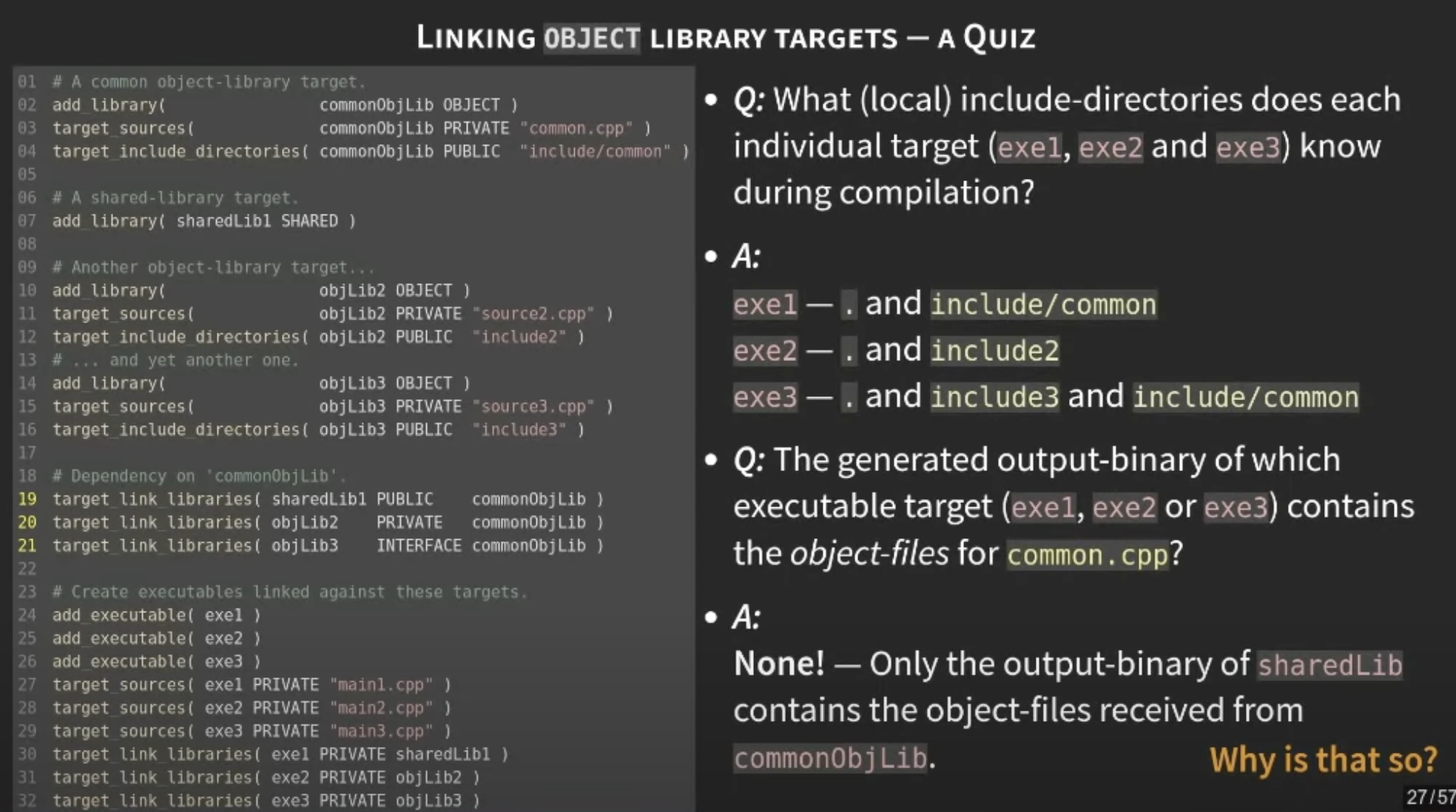

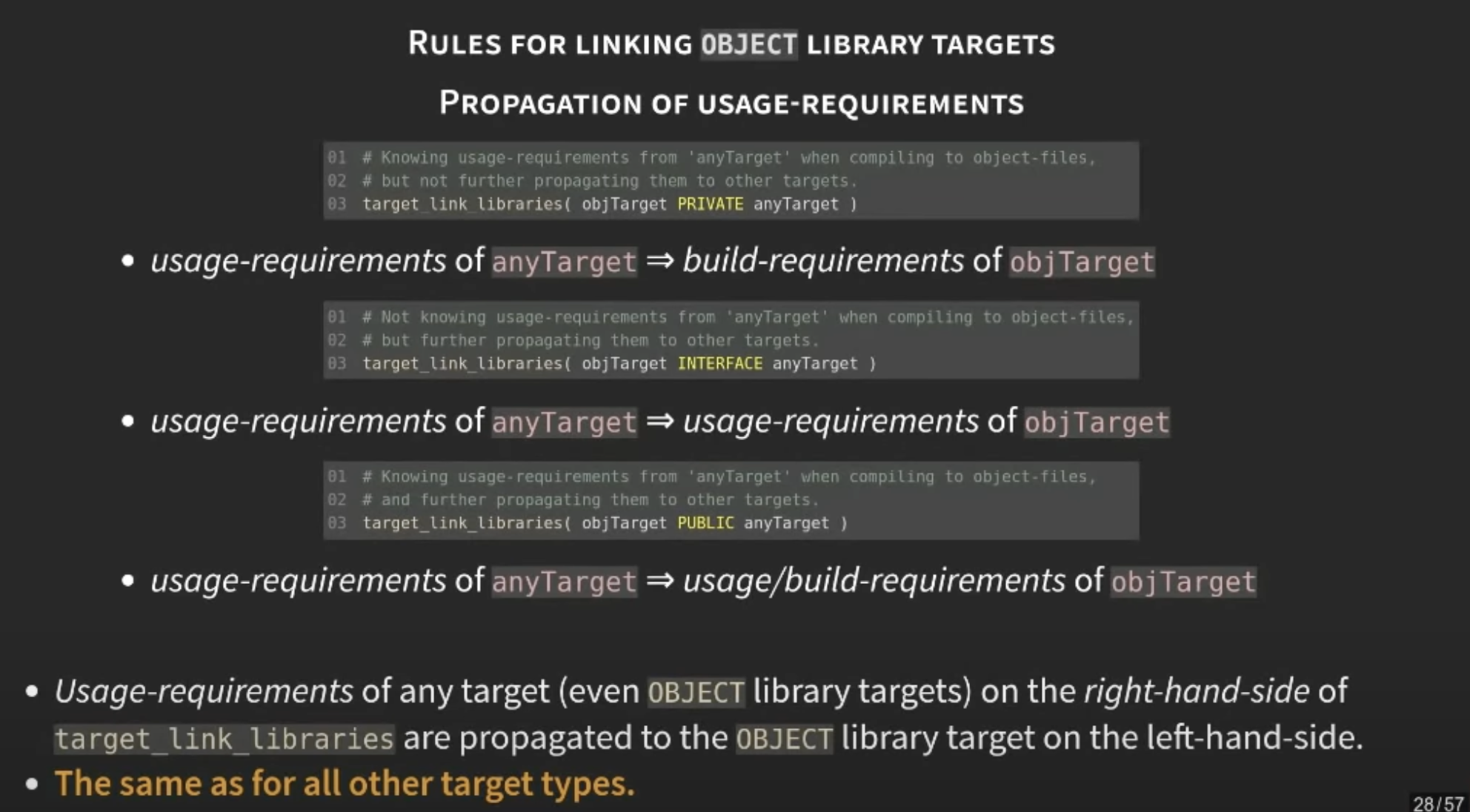

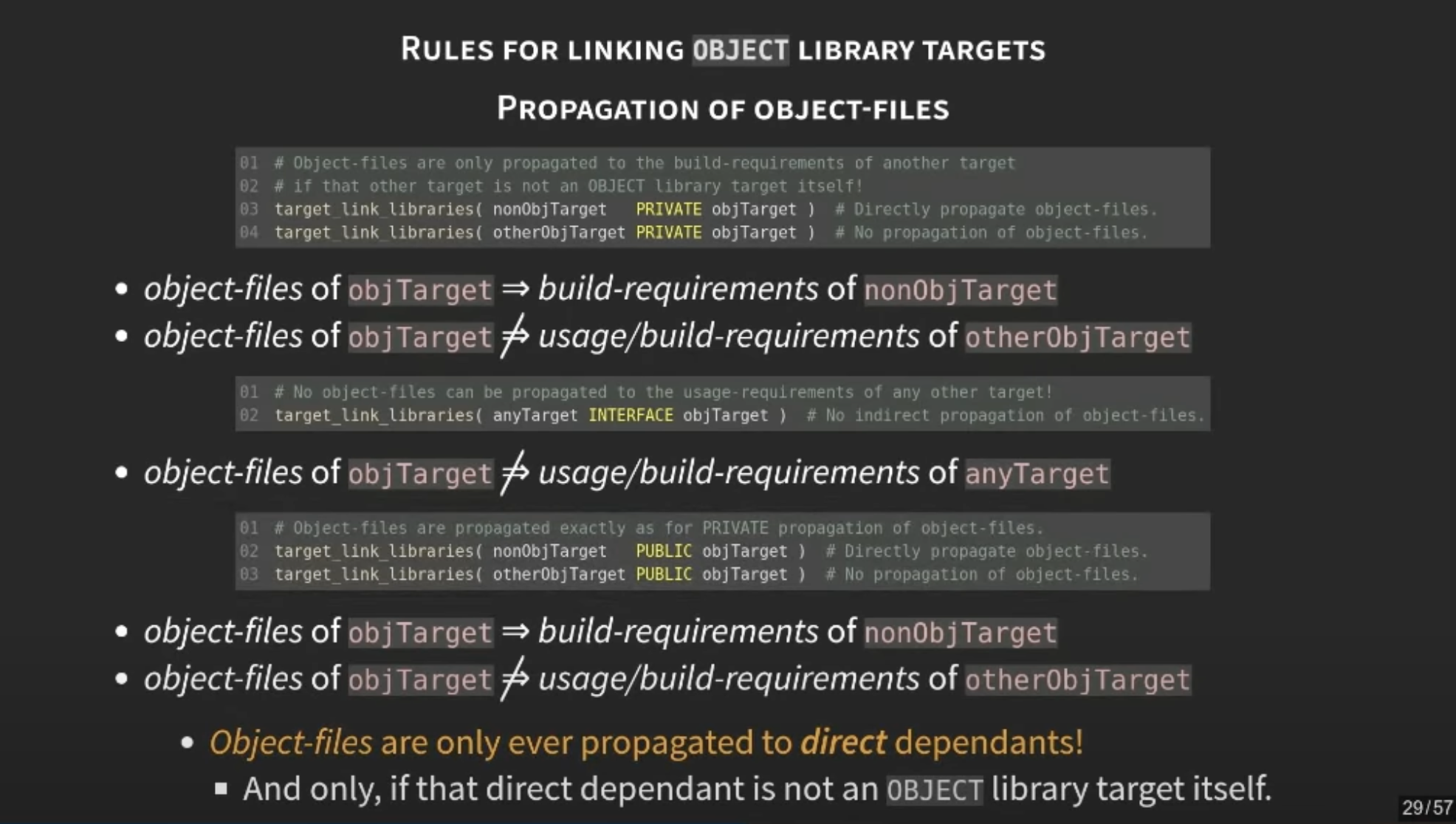

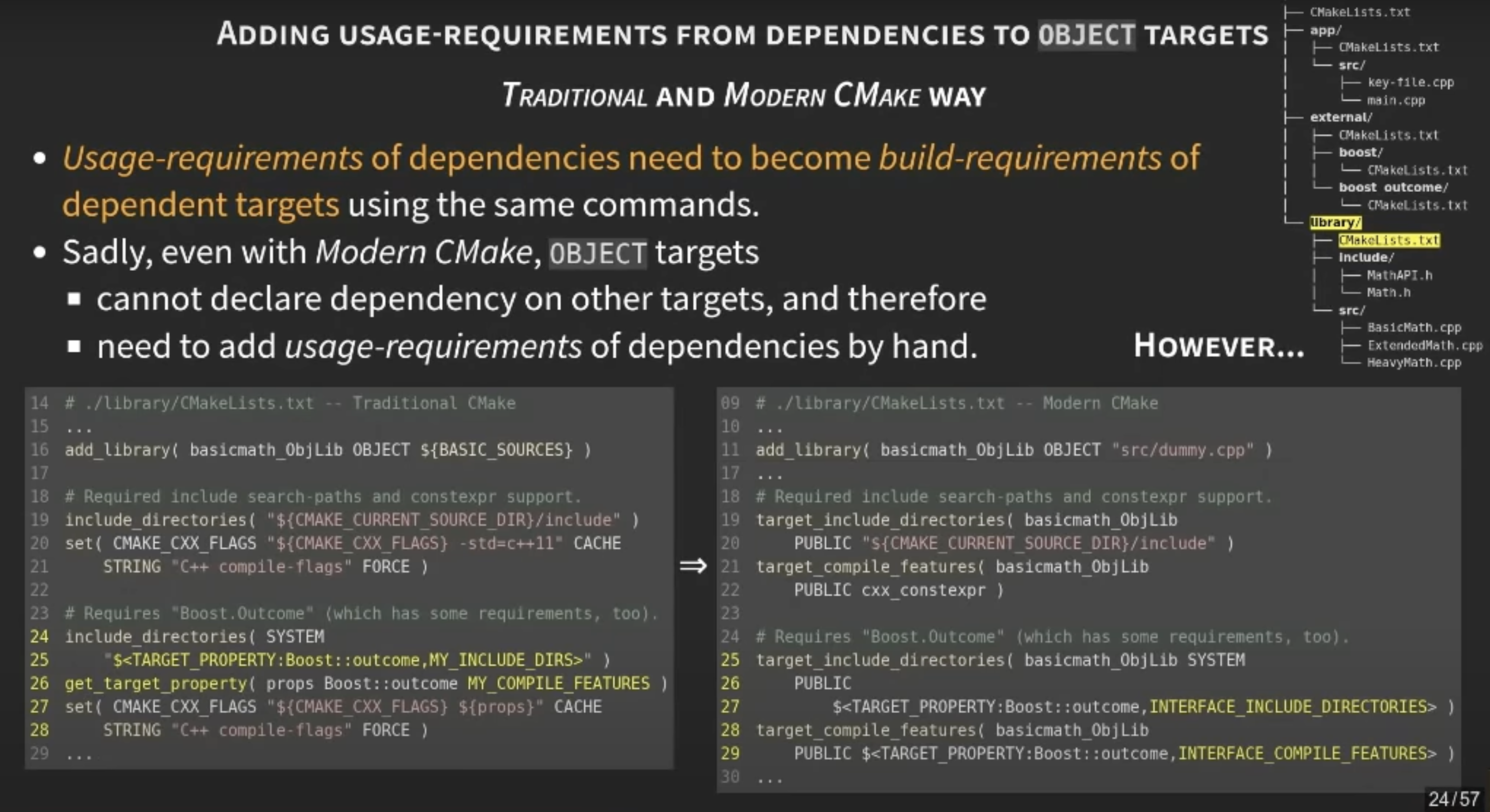

Object libraries some peculiarities