100 Go Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Code and Project Organization

- 1. Unintended variable shadowing (变量遮蔽)

- 2. Unnecessary nested code (代码嵌套过深)

- 3. Misusing init functions (init 函数误用)

- 4. Overusing getters and setters (过度使用 Getter/Setter)

- 5. Interface pollution (接口污染)

- 6. Interface on the producer side (生产者端接口)

- 7. Returning interfaces (返回接口)

- 8. any says nothing (滥用 any 类型)

- 9. Being confused about when to use generics (泛型使用不当)

- 10. Not being aware of the possible problems with type embedding (类型嵌入风险)

- 11. Not using the functional options pattern (缺少函数选项模式)

- 12. Project misorganization (project structure and package organization) (项目结构与包名管理)

- 13. Creating utility packages (避免使用通用、无意义的包名)

- 14. Ignoring package name collisions (变量名与包名发生冲突)

- 15. Missing code documentation (缺少代码文档)

- 16. Not using linters (未使用 linters)

- Data Types

- Refer

Source code and community space of 📖 100 Go Mistakes and How to Avoid Them, published by Manning in August 2022. Read online: 100go.co

Meanwhile, it’s also open to the community. If you believe that a common Go mistake should be added, please create an issue.

Code and Project Organization

1. Unintended variable shadowing (变量遮蔽)

TL;DR

Avoiding shadowed variables can help prevent mistakes like referencing the wrong variable or confusing readers.

Variable shadowing occurs when a variable name is redeclared in an inner block, but this practice is prone to mistakes. Imposing a rule to forbid shadowed variables depends on personal taste. For example, sometimes it can be convenient to reuse an existing variable name like err for errors. Yet, in general, we should remain cautious because we now know that we can face a scenario where the code compiles, but the variable that receives the value is not the one expected.

代码示例:

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

_ = listing1()

_ = listing2()

_ = listing3()

_ = listing4()

}

func listing1() error {

var client *http.Client

if tracing {

client, err := createClientWithTracing()

if err != nil {

return err

}

log.Println(client)

} else {

client, err := createDefaultClient()

if err != nil {

return err

}

log.Println(client)

}

_ = client

return nil

}

func listing2() error {

var client *http.Client

if tracing {

c, err := createClientWithTracing()

if err != nil {

return err

}

client = c

} else {

c, err := createDefaultClient()

if err != nil {

return err

}

client = c

}

_ = client

return nil

}

func listing3() error {

var client *http.Client

var err error

if tracing {

client, err = createClientWithTracing()

if err != nil {

return err

}

} else {

client, err = createDefaultClient()

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

_ = client

return nil

}

func listing4() error {

var client *http.Client

var err error

if tracing {

client, err = createClientWithTracing()

} else {

client, err = createDefaultClient()

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

_ = client

return nil

}

var tracing bool

func createClientWithTracing() (*http.Client, error) {

return nil, nil

}

func createDefaultClient() (*http.Client, error) {

return nil, nil

}

问题解析:

在 listing1() 中出现了变量遮蔽问题::= 操作符在 if 块内创建了新的局部变量 client,而不是修改外部的 client 变量。所以外部 client 始终是 nil。

func listing1() error {

var client *http.Client // 外部声明的 client 变量

if tracing {

// 这里使用 := 重新声明了新的 client 和 err 变量

client, err := createClientWithTracing() // 这里创建了新的 client 变量

if err != nil {

return err

}

log.Println(client) // 打印的是内部 client

}

// ...

_ = client // 这里使用的是外部的 client,仍然是 nil!

return nil

}

优化方案:

- 解决方案1:

listing2()。使用不同的变量名c接收返回值,然后赋值给外部client,避免变量遮蔽,但需要额外的临时变量。 - 解决方案2:

listing3()。预先声明所有变量,使用赋值操作符=而不是短声明:=,代码较冗长,错误处理重复。 - 最佳实践:

listing4()。预先声明变量,逻辑与错误处理分离,最简洁,避免重复代码。

避免遮蔽的建议:

- 使用 IDE 或 linter 工具检测遮蔽

- 考虑禁用变量遮蔽的代码规范

- 除非有明确理由,否则避免重用变量名

2. Unnecessary nested code (代码嵌套过深)

TL;DR

Avoiding nested levels and keeping the happy path aligned on the left makes building a mental code model easier.

In general, the more nested levels a function requires, the more complex it is to read and understand. Let’s see some different applications of this rule to optimize our code for readability:

When an if block returns, we should omit the else block in all cases. For example, we shouldn’t write:

if foo() {

// ...

return true

} else {

// ...

}

Instead, we omit the else block like this:

if foo() {

// ...

return true

}

// ...

We can also follow this logic with a non-happy path:

if s != "" {

// ...

} else {

return errors.New("empty string")

}

Here, an empty s represents the non-happy path. Hence, we should flip the condition like so:

if s == "" {

return errors.New("empty string")

}

// ...

Writing readable code is an important challenge for every developer. Striving to reduce the number of nested blocks, aligning the happy path on the left, and returning as early as possible are concrete means to improve our code’s readability.

代码示例:

package main

import "errors"

// 反面示例

func join1(s1, s2 string, max int) (string, error) {

if s1 == "" {

return "", errors.New("s1 is empty")

} else {

if s2 == "" {

return "", errors.New("s2 is empty")

} else {

concat, err := concatenate(s1, s2)

if err != nil {

return "", err

} else {

if len(concat) > max {

return concat[:max], nil

} else {

return concat, nil

}

}

}

}

}

// 建议用法

func join2(s1, s2 string, max int) (string, error) {

if s1 == "" {

return "", errors.New("s1 is empty")

}

if s2 == "" {

return "", errors.New("s2 is empty")

}

concat, err := concatenate(s1, s2)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

if len(concat) > max {

return concat[:max], nil

}

return concat, nil

}

func concatenate(s1, s2 string) (string, error) {

return "", nil

}

3. Misusing init functions (init 函数误用)

TL;DR

When initializing variables, remember that init functions have limited error handling and make state handling and testing more complex. In most cases, initializations should be handled as specific functions.

An init function is a function used to initialize the state of an application. It takes no arguments and returns no result (a func() function). When a package is initialized, all the constant and variable declarations in the package are evaluated. Then, the init functions are executed.

Init functions can lead to some issues:

- They can limit error management.

- They can complicate how to implement tests (for example, an external dependency must be set up, which may not be necessary for the scope of unit tests).

- If the initialization requires us to set a state, that has to be done through global variables.

We should be cautious with init functions. They can be helpful in some situations, however, such as defining static configuration. Otherwise, and in most cases, we should handle initializations through ad hoc functions.

init 函数是 Go 语言中的特殊函数,用于包初始化:

- 无参数,无返回值

- 在程序启动时自动执行

- 一个包可以有多个 init 函数,按声明顺序执行

- 执行时机:包级变量初始化后,main 函数执行前

示例1:多个 init 函数

// main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/teivah/100-go-mistakes/src/02-code-project-organization/3-init-functions/redis"

)

func init() {

fmt.Println("init 1") // 第二个执行

}

func init() {

fmt.Println("init 2") // 第三个执行

}

func main() {

err := redis.Store("foo", "bar")

_ = err

}

// redis.go

package redis

import "fmt"

func init() {

fmt.Println("redis") // 第一个执行

}

func Store(key, value string) error {

return nil

}

执行顺序:

- 导入 redis 包 → 执行

redis.init() - 执行 main 包的 init 函数(按声明顺序)

- 执行 main 函数

输出:

redis

init 1

init 2

示例2:数据库连接初始化

package main

import (

"database/sql"

"log"

"os"

)

var db *sql.DB // 全局变量

func init() {

dataSourceName := os.Getenv("MYSQL_DATA_SOURCE_NAME")

d, err := sql.Open("mysql", dataSourceName)

if err != nil {

log.Panic(err) // 错误处理受限

}

err = d.Ping()

if err != nil {

log.Panic(err) // 只能 panic,无法优雅处理

}

db = d // 必须使用全局变量

}

func createClient(dataSourceName string) (*sql.DB, error) {

db, err := sql.Open("mysql", dataSourceName)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if err = db.Ping(); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return db, nil

}

init 函数的问题:

- init 函数错误处理受限。如果初始化失败,只能 panic,无法返回错误给调用者,程序直接崩溃

func init() {

// 如果初始化失败,只能 panic

// 无法返回错误给调用者

log.Panic(err) // 程序直接崩溃

}

// 对比普通函数

func initDB() error {

// 可以返回错误,让调用者决定如何处理

return errors.New("connection failed")

}

- 测试复杂化

- 自动执行,无法控制时机

- 依赖全局变量,测试相互影响

- 需要设置环境变量,测试配置复杂

// 测试时需要:go test -env "MYSQL_DATA_SOURCE_NAME=..."

// 或者需要模拟全局状态

- 依赖全局变量

- 全局状态难以维护

- 并发安全问题

- 代码耦合度高

var db *sql.DB // 全局变量

func init() {

db = d // 必须用全局变量存储状态

}

- 执行顺序不可控

// 多个包的 init 函数执行顺序

// 由导入依赖决定,不易理解和维护

package A: init() → package B: init() → main.init()

init 函数的适用场景:

package config

var DefaultConfig Config

func init() {

// 初始化静态配置(无外部依赖)

DefaultConfig = Config{

Timeout: 30 * time.Second,

MaxConn: 100,

}

}

合理用途:

- 静态配置初始化

- 验证包级变量合理性

- 注册驱动(如 database/sql 驱动注册)

- 设置默认行为

不适合的情况:

// 不适合:有外部依赖的初始化

func init() {

// 从环境变量读取配置(可能有环境依赖)

// 连接数据库(可能失败,需要错误处理)

// 启动网络服务(应延迟初始化)

}

最佳实践建议:

- 使用显式初始化函数

// 更好的方式

type App struct {

db *sql.DB

// 其他依赖

}

func NewApp() (*App, error) {

db, err := createClient(os.Getenv("MYSQL_DATA_SOURCE_NAME"))

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("init db: %w", err)

}

return &App{db: db}, nil

}

func main() {

app, err := NewApp()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err) // 可控的错误处理

}

// 使用 app

}

- 依赖注入

func CreateDB(dataSourceName string) (*sql.DB, error) {

// 可测试,可控制

}

func main() {

db, err := CreateDB(os.Getenv("MYSQL_DATA_SOURCE_NAME"))

if err != nil {

// 优雅处理

}

}

- 配置对象模式

type Config struct {

DBDataSource string

// 其他配置

}

func LoadConfig() (Config, error) {

// 显式加载配置,可返回错误

}

func main() {

cfg, err := LoadConfig()

if err != nil {

// 处理错误

}

db, err := createClient(cfg.DBDataSource)

// ...

}

总结:

init 函数的主要问题:

- 错误处理能力差:只能 panic,无法优雅处理

- 测试困难:自动执行,依赖全局状态

- 隐式行为:代码逻辑不明显,维护困难

- 执行顺序依赖:由导入顺序决定,不易理解

建议:除非是简单的静态初始化,否则使用显式初始化函数,这样代码更清晰、更可测试、错误处理更完善。

4. Overusing getters and setters (过度使用 Getter/Setter)

TL;DR

Forcing the use of getters and setters isn’t idiomatic in Go. Being pragmatic and finding the right balance between efficiency and blindly following certain idioms should be the way to go.

Data encapsulation refers to hiding the values or state of an object. Getters and setters are means to enable encapsulation by providing exported methods on top of unexported object fields.

In Go, there is no automatic support for getters and setters as we see in some languages. It is also considered neither mandatory nor idiomatic to use getters and setters to access struct fields. We shouldn’t overwhelm our code with getters and setters on structs if they don’t bring any value. We should be pragmatic and strive to find the right balance between efficiency and following idioms that are sometimes considered indisputable in other programming paradigms.

Remember that Go is a unique language designed for many characteristics, including simplicity. However, if we find a need for getters and setters or, as mentioned, foresee a future need while guaranteeing forward compatibility, there’s nothing wrong with using them.

Go 语言的设计哲学强调简洁和实用,不强制使用 getter 和 setter。这与 Java 等语言形成鲜明对比。

Go 语言的独特设计:

- 没有自动属性支持

// Java风格(自动属性)

private String name;

public String getName() { return name; }

public void setName(String name) { this.name = name; }

// Go风格(直接访问或手动方法)

type Person struct {

Name string // 直接导出,简单情况

}

- 访问控制通过大小写实现

// 导出字段(公开)

type Person struct {

Name string // 大写开头 - 公开访问

Age int // 大写开头 - 公开访问

}

// 非导出字段(私有)

type person struct {

name string // 小写开头 - 包内访问

age int // 小写开头 - 包内访问

}

何时使用 Getter/Setter?

适合使用的情况1:需要验证逻辑

type BankAccount struct {

balance float64 // 私有,需要保护

}

// Getter

func (b *BankAccount) Balance() float64 {

return b.balance

}

// Setter(带验证)

func (b *BankAccount) Deposit(amount float64) error {

if amount <= 0 {

return fmt.Errorf("存款金额必须为正数")

}

b.balance += amount

return nil

}

func (b *BankAccount) Withdraw(amount float64) error {

if amount <= 0 {

return fmt.Errorf("取款金额必须为正数")

}

if amount > b.balance {

return fmt.Errorf("余额不足")

}

b.balance -= amount

return nil

}

适合使用的情况2:需要计算或派生值

type Rectangle struct {

width float64

height float64

}

// Getter(计算值)

func (r *Rectangle) Area() float64 {

return r.width * r.height

}

func (r *Rectangle) Perimeter() float64 {

return 2 * (r.width + r.height)

}

适合使用的情况3:需要延迟初始化或缓存

type ExpensiveResource struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

data []byte

loaded bool

}

// Getter(延迟加载)

func (e *ExpensiveResource) Data() ([]byte, error) {

e.mu.RLock()

if e.loaded {

data := e.data

e.mu.RUnlock()

return data, nil

}

e.mu.RUnlock()

// 加写锁并加载

e.mu.Lock()

defer e.mu.Unlock()

if !e.loaded {

var err error

e.data, err = loadExpensiveData()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

e.loaded = true

}

return e.data, nil

}

不需要使用的情况

- 简单数据传输对象(DTO)

// 直接导出字段更简洁

type Point struct {

X int

Y int

}

// 使用简单明了

p := Point{X: 10, Y: 20}

fmt.Printf("Point: (%d, %d)\n", p.X, p.Y)

- 配置结构

type Config struct {

Host string

Port int

Timeout time.Duration

MaxConns int

}

// 直接初始化更清晰

config := Config{

Host: "localhost",

Port: 8080,

Timeout: 30 * time.Second,

MaxConns: 100,

}

- 内部辅助结构

// 只在包内使用,可以直接访问

type internalState struct {

counter int

lastUpdate time.Time

active bool

}

func (is *internalState) increment() {

is.counter++

is.lastUpdate = time.Now()

}

总结建议

- 默认直接导出字段:Go 社区倾向于简单直接的访问方式

- 有理由时才封装:

- 需要验证逻辑

- 需要维护不变性

- 需要派生计算值

- 涉及并发安全

- 保持 API 稳定:如果结构体是公开 API 的一部分,提前考虑是否需要封装

- 信任使用者:Go 哲学假设开发者知道自己在做什么,不过度保护

- 文档说明:通过文档说明约束,而不是强制封装

Go 语言的这种务实态度正是其魅力所在——在简洁性和封装性之间找到平衡,避免不必要的复杂性。

5. Interface pollution (接口污染)

TL;DR

Abstractions should be discovered, not created. To prevent unnecessary complexity, create an interface when you need it and not when you foresee needing it, or if you can at least prove the abstraction to be a valid one.

- More: Interface pollution

- NotebookML 解读:https://notebooklm.google.com/notebook/d86b149b-bc4d-4587-9a75-7083db063b62?authuser=1

Interfaces are one of the cornerstones(基石) of the Go language when designing and structuring our code. However, like many tools or concepts, abusing them is generally not a good idea. Interface pollution is about overwhelming our code with unnecessary abstractions, making it harder to understand. It’s a common mistake made by developers coming from another language with different habits. Before delving into the topic, let’s refresh our minds about Go’s interfaces. Then, we will see when it’s appropriate to use interfaces and when it may be considered pollution.

Go 语言中 “接口污染” 的概念,即过度或不必要地使用接口,反而会让代码变得复杂难懂。核心观点是:接口的抽象应该是“被发现”,而不是“被创造”。

Concepts (interface)

An interface provides a way to specify the behavior of an object. We use interfaces to create common abstractions that multiple objects can implement. What makes Go interfaces so different is that they are satisfied implicitly. There is no explicit keyword like implements to mark that an object X implements interface Y.

To understand what makes interfaces so powerful, we will dig into two popular ones from the standard library: io.Reader and io.Writer. The io package provides abstractions for I/O primitives. Among these abstractions, io.Reader relates to reading data from a data source and io.Writer to writing data to a target, as represented in the next figure:

The io.Reader contains a single Read method:

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

Custom implementations of the io.Reader interface should accept a slice of bytes, filling it with its data and returning either the number of bytes read or an error.

On the other hand, io.Writer defines a single method, Write:

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

Custom implementations of io.Writer should write the data coming from a slice to a target and return either the number of bytes written or an error. Therefore, both interfaces provide fundamental abstractions:

io.Readerreads data from a sourceio.Writerwrites data to a target

What is the rationale(根本原因) for having these two interfaces in the language? What is the point of creating these abstractions?

Let’s assume we need to implement a function that should copy the content of one file to another. We could create a specific function that would take as input two *os.File. Or, we can choose to create a more generic function using io.Reader and io.Writer abstractions:

func copySourceToDest(source io.Reader, dest io.Writer) error {

// ...

}

This function would work with *os.File parameters (as *os.File implements both io.Reader and io.Writer) and any other type that would implement these interfaces. For example, we could create our own io.Writer that writes to a database, and the code would remain the same. It increases the genericity of the function; hence, its reusability.

Furthermore, writing a unit test for this function is easier because, instead of having to handle files, we can use the strings and bytes packages that provide helpful implementations:

func TestCopySourceToDest(t *testing.T) {

const input = "foo"

source := strings.NewReader(input) // Creates an io.Reader

dest := bytes.NewBuffer(make([]byte, 0)) // Creates an io.Writer

err := copySourceToDest(source, dest) // Calls copySourceToDest from a *strings.Reader and a *bytes.Buffer

if err != nil {

t.FailNow()

}

got := dest.String()

if got != input {

t.Errorf("expected: %s, got: %s", input, got)

}

}

In the example, source is a *strings.Reader, whereas dest is a *bytes.Buffer. Here, we test the behavior of copySourceToDest without creating any files.

While designing interfaces, the granularity(粒度) (how many methods the interface contains) is also something to keep in mind. A known proverb in Go relates to how big an interface should be:

Indeed, adding methods to an interface can decrease its level of reusability. io.Reader and io.Writer are powerful abstractions because they cannot get any simpler. Furthermore, we can also combine fine-grained interfaces to create higher-level abstractions. This is the case with io.ReadWriter, which combines the reader and writer behaviors:

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}

When to use interfaces

When should we create interfaces in Go? Let’s look at three concrete use cases where interfaces are usually considered to bring value. Note that the goal isn’t to be exhaustive(详尽无遗的) because the more cases we add, the more they would depend on the context. However, these three cases should give us a general idea:

- Common behavior

- Decoupling

- Restricting behavior

Common behavior

The first option we will discuss is to use interfaces when multiple types implement a common behavior. In such a case, we can factor out the behavior inside an interface. If we look at the standard library, we can find many examples of such a use case. For example, sorting a collection can be factored out via three methods:

- Retrieving the number of elements in the collection

- Reporting whether one element must be sorted before another

- Swapping two elements

Hence, the following interface was added to the sort package:

type Interface interface {

Len() int // Number of elements

Less(i, j int) bool // Checks two elements

Swap(i, j int) // Swaps two elements

}

This interface has a strong potential for reusability because it encompasses the common behavior to sort any collection that is index-based.

Throughout the sort package, we can find dozens of implementations. If at some point we compute a collection of integers, for example, and we want to sort it, are we necessarily interested in the implementation type? Is it important whether the sorting algorithm is a merge sort or a quicksort? In many cases, we don’t care. Hence, the sorting behavior can be abstracted, and we can depend on the sort.Interface.

Finding the right abstraction to factor out a behavior can also bring many benefits. For example, the sort package provides utility functions that also rely on sort.Interface, such as checking whether a collection is already sorted. For instance:

func IsSorted(data Interface) bool {

n := data.Len()

for i := n - 1; i > 0; i-- {

if data.Less(i, i-1) {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Because sort.Interface is the right level of abstraction, it makes it highly valuable.

Decoupling

Another important use case is about decoupling our code from an implementation. If we rely on an abstraction instead of a concrete implementation, the implementation itself can be replaced with another without even having to change our code. This is the Liskov Substitution Principle (the L in Robert C. Martin’s SOLID design principles).

In object-oriented programming, SOLID is a mnemonic acronym for five principles intended to make source code more understandable, flexible, and maintainable. Although the principles apply to object-oriented programming, they can also form a core philosophy for methodologies such as agile software development and adaptive software development.

One benefit of decoupling can be related to unit testing. Let’s assume we want to implement a CreateNewCustomer method that creates a new customer and stores it. We decide to rely on the concrete implementation directly (let’s say a mysql.Store struct):

type CustomerService struct {

store mysql.Store // Depends on the concrete implementation

}

func (cs CustomerService) CreateNewCustomer(id string) error {

customer := Customer{id: id}

return cs.store.StoreCustomer(customer)

}

Now, what if we want to test this method? Because customerService relies on the actual implementation to store a Customer, we are obliged to test it through integration tests, which requires spinning up a MySQL instance (unless we use an alternative technique such as go-sqlmock, but this isn’t the scope of this section). Although integration tests are helpful, that’s not always what we want to do. To give us more flexibility, we should decouple CustomerService from the actual implementation, which can be done via an interface like so:

type customerStorer interface { // Creates a storage abstraction

StoreCustomer(Customer) error

}

type CustomerService struct {

storer customerStorer // Decouples CustomerService from the actual implementation

}

func (cs CustomerService) CreateNewCustomer(id string) error {

customer := Customer{id: id}

return cs.storer.StoreCustomer(customer)

}

Because storing a customer is now done via an interface, this gives us more flexibility in how we want to test the method. For instance, we can:

- Use the concrete implementation via integration tests

- Use a mock (or any kind of test double) via unit tests

- Or both

Restricting behavior

The last use case we will discuss can be pretty counterintuitive(违反常理的) at first sight. It’s about restricting a type to a specific behavior. Let’s imagine we implement a custom configuration package to deal with dynamic configuration. We create a specific container for int configurations via an IntConfig struct that also exposes two methods: Get and Set. Here’s how that code would look:

type IntConfig struct {

// ...

}

func (c *IntConfig) Get() int {

// Retrieve configuration

}

func (c *IntConfig) Set(value int) {

// Update configuration

}

Now, suppose we receive an IntConfig that holds some specific configuration, such as a threshold. Yet, in our code, we are only interested in retrieving the configuration value, and we want to prevent updating it. How can we enforce that, semantically, this configuration is read-only, if we don’t want to change our configuration package? By creating an abstraction that restricts the behavior to retrieving only a config value:

type intConfigGetter interface {

Get() int

}

Then, in our code, we can rely on intConfigGetter instead of the concrete implementation:

type Foo struct {

threshold intConfigGetter

}

func NewFoo(threshold intConfigGetter) Foo { // Injects the configuration getter

return Foo{threshold: threshold}

}

func (f Foo) Bar() {

threshold := f.threshold.Get() // Reads the configuration

// ...

}

In this example, the configuration getter is injected into the NewFoo factory method. It doesn’t impact a client of this function because it can still pass an IntConfig struct as it implements intConfigGetter. Then, we can only read the configuration in the Bar method, not modify it. Therefore, we can also use interfaces to restrict a type to a specific behavior for various reasons, such as semantics enforcement.

Interface pollution

It’s fairly common to see interfaces being overused in Go projects. Perhaps the developer’s background was C# or Java, and they found it natural to create interfaces before concrete types. However, this isn’t how things should work in Go.

As we discussed, interfaces are made to create abstractions. And the main caveat(警告; 提醒) when programming meets abstractions is remembering that abstractions should be discovered, not created. What does this mean? It means we shouldn’t start creating abstractions in our code if there is no immediate reason to do so. We shouldn’t design with interfaces but wait for a concrete need. Said differently, we should create an interface when we need it, not when we foresee that we could need it.

In summary, we should be cautious when creating abstractions in our code—abstractions should be discovered, not created. It’s common for us, software developers, to overengineer our code by trying to guess what the perfect level of abstraction is, based on what we think we might need later. This process should be avoided because, in most cases, it pollutes our code with unnecessary abstractions, making it more complex to read.

Let’s not try to solve a problem abstractly but solve what has to be solved now. Last, but not least, if it’s unclear how an interface makes the code better, we should probably consider removing it to make our code simpler.

分析解释

核心定义与成因

接口污染的核心在于过度使用抽象。这通常发生在使用习惯了 C# 或 Java 等语言的开发者身上,他们习惯在编写具体类型之前先定义接口。在 Go 中,这种“预见性”的设计往往会导致代码中出现大量没有实际价值的间接层。

为什么这是一个问题?

- 增加复杂性:无用的间接层会干扰代码流,使阅读、理解和推理代码变得更加困难。

- 降低可读性:如果接口的用途不明确,调用者往往需要花费更多精力去寻找真正的实现逻辑。

- 性能开销:虽然在许多场景下微不足道,但通过接口调用方法需要在运行时进行哈希表查找以定位具体类型,这会带来一定的性能损耗。

Go 的核心哲学:发现而非创造

来源强调了一个关键原则:抽象应该是被发现的,而不是被创造的(Abstractions should be discovered, not created)。

- 开发者不应该为了“预见”未来可能的需求而提前创建接口。

- 只有当接口能让代码变得更好(例如提高可重用性或简化测试)时,才应该引入它。

- Rob Pike 曾指出:“不要针对接口设计,要发现接口”。

什么时候不属于接口污染?

这些场景下接口能带来明确的价值:

- 共同行为(Common behavior):当多个类型需要实现相同的逻辑(如标准库中的

sort.Interface或io.Reader)时,通过接口提取共性。 - 解耦(Decoupling):为了让代码不依赖于具体的实现(例如数据库存储),从而方便进行单元测试(使用

Mock对象)或在未来更换实现方案。 - 限制行为(Restricting behavior):通过接口强制实施语义约束,例如将一个具有读写能力的结构体限制为只读。

总结建议

如果你发现很难解释某个接口存在的理由,或者直接调用具体实现会让代码更简洁,那么这个接口很可能就是“污染”。在 Go 中,建议先编写具体的实现,等到实际需要解耦或处理多种类型时再提取接口。

比喻理解

接口就像是翻译官。在只有两个说相同语言的人对话时,强制在中间塞进一个翻译官(接口)只会让沟通变慢且容易产生误解;只有当一个说中文的人需要和多个说不同外语的人(多种具体类型)交流,或者需要确保对话内容可以随时录音存档(测试解耦)时,翻译官的存在才有意义。

接口就像是一份合同。在生意还没开始做(没有实际业务逻辑)之前,就急着起草成百上千份细节详尽的合同(过度设计接口),只会让简单的买卖变得复杂无比。正确的做法是先开始交易(编写具体代码),当发现有多个合作伙伴都在做同样的事,或者需要规避某些风险时,再针对性地签一份简洁有效的合同(发现并提取接口)。

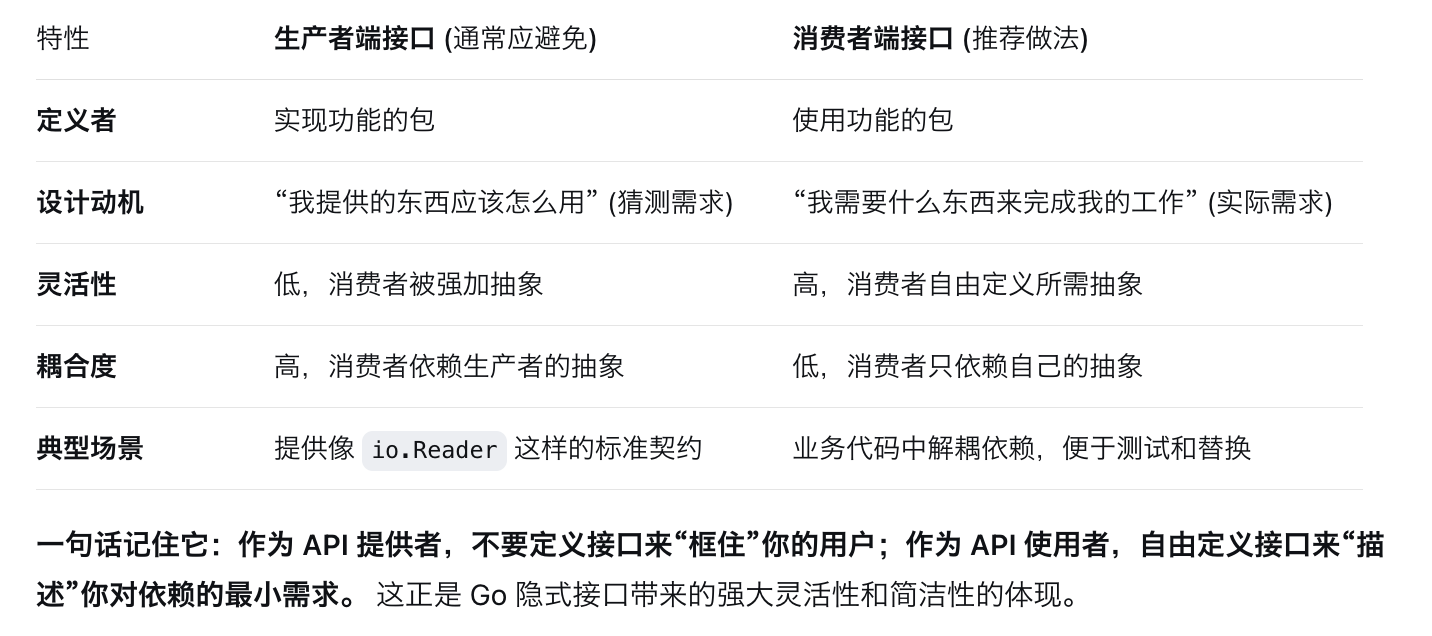

6. Interface on the producer side (生产者端接口)

TL;DR

Keeping interfaces on the client side avoids unnecessary abstractions.

Interfaces are satisfied implicitly in Go, which tends to be a gamechanger compared to languages with an explicit implementation. In most cases, the approach to follow is similar to what we described in the previous section: abstractions should be discovered, not created. This means that it’s not up to the producer to force a given abstraction for all the clients. Instead, it’s up to the client to decide whether it needs some form of abstraction and then determine the best abstraction level for its needs.

An interface should live on the consumer side in most cases. However, in particular contexts (for example, when we know—not foresee—that an abstraction will be helpful for consumers), we may want to have it on the producer side. If we do, we should strive to keep it as minimal as possible, increasing its reusability potential and making it more easily composable.

“生产者端接口” 这一话题讨论的是:接口应该由谁定义?是实现方(生产者),还是使用方(消费者)?Go 社区的最佳实践给出了明确答案:在绝大多数情况下,接口应该定义在使用方(消费者)的代码中。这与很多面向对象语言(如 Java、C#)的惯用法截然不同,其根源在于 Go 接口的隐式满足特性。

生产者端定义接口的问题:

如果生产者(例如一个 MySQLUserRepository 的实现包)自己定义了一个 IUserRepository 接口,然后让实现去满足它,这会导致:

- 不必要的耦合:生产者锁定了抽象层次,所有消费者都被迫使用这个可能包含他们不需要的方法的接口。

- 僵化的设计:接口难以演进,因为任何修改都可能破坏所有实现者和消费者。

- 过度设计:生产者容易设计出“大而全”的接口,因为它试图预测所有可能的用途。

消费者端定义接口的优势:

消费者(例如业务逻辑层)根据自己需要的方法来定义一个接口。

示例:

// 生产者包 (producer) - 提供具体实现

package db

type MySQLUserRepository struct { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLUserRepository) CreateUser(user User) error { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLUserRepository) GetUserByID(id int) (*User, error) { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLUserRepository) UpdateUser(user User) error { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLUserRepository) DeleteUser(id int) error { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLUserRepository) RunComplexAnalytics() (*Report, error) { /* ... */ } // 某个复杂方法

// 消费者包 (consumer) - 定义自己所需的接口

package service

// UserSaver 是消费者为自己定义的接口,只包含它真正需要的方法

type UserSaver interface {

CreateUser(user User) error

}

func ProcessSignup(saver UserSaver, user User) error {

// 这里只关心“保存”这个行为

return saver.CreateUser(user)

}

// UserGetter 是另一个消费者定义的接口,用于不同的场景

type UserGetter interface {

GetUserByID(id int) (*User, error)

}

func GetUserProfile(getter UserGetter, id int) (*User, error) {

return getter.GetUserByID(id)

}

优势:

- 解耦与灵活:消费者

service包完全不依赖生产者的具体类型(MySQLUserRepository),只依赖自己定义的小接口。这符合依赖倒置原则。 - 按需抽象

:ProcessSignup函数只需要一个能CreateUser的东西,它就定义这样一个极简接口。这避免了依赖不需要的方法(如RunComplexAnalytics)。 - 易于测试:为

UserSaver或UserGetter编写模拟测试非常容易。 - 组合自由:生产者

db.MySQLUserRepository隐式地满足了这些接口,无需任何声明。未来可以轻松换用其他存储(如PostgresUserRepository、MockRepository),只要它们实现了相应的方法。

何时放在生产者端?(例外情况)

原则总有例外。在以下情况下,由生产者定义接口是合理的:

- 提供通用、稳定的契约:当你提供的不是一个具体实现,而是一个被广泛认可、极简且稳定的行为契约时。标准库中的

io.Reader、io.Writer、error接口就是典范。它们定义了计算机科学中的基础概念,几乎不会改变。 - 在包内部隐藏实现细节:在包内部使用接口来解耦具体实现,对外部消费者隐藏复杂结构。但这属于内部实现细节,对外暴露的通常仍是函数或结构体。

- 提供可选功能:例如

sql.Driver接口,它定义了数据库驱动必须实现的方法,这是一个框架级的、由生产者(database/sql包)定义的“插件”接口。

关键点:当你决定在生产者端定义接口时,务必遵循 “接口越小越好” 的原则。一个只包含1-3个方法的接口,远比一个20个方法的“全能”接口更有用、更持久、更容易组合。

7. Returning interfaces (返回接口)

TL;DR

To prevent being restricted in terms of flexibility, a function shouldn’t return interfaces but concrete implementations in most cases. Conversely, a function should accept interfaces whenever possible.

In most cases, we shouldn’t return interfaces but concrete implementations. Otherwise, it can make our design more complex due to package dependencies and can restrict flexibility because all the clients would have to rely on the same abstraction. Again, the conclusion is similar to the previous sections: if we know (not foresee) that an abstraction will be helpful for clients, we can consider returning an interface. Otherwise, we shouldn’t force abstractions; they should be discovered by clients. If a client needs to abstract an implementation for whatever reason, it can still do that on the client’s side.

函数应该返回具体类型,而不是接口类型。但函数应该尽可能接受接口作为参数。这个原则与”生产者端接口”的思想一脉相承,都是为了保持最大的灵活性和避免过早抽象。

这个原则的核心思想是:作为API提供者,不要替用户做决定。给他们具体的东西,让他们自己决定如何使用和抽象。

为什么不应该返回接口?

问题1:限制灵活性

当函数返回接口时,你强制所有调用者都使用相同的抽象。这意味着:

// ❌ 不推荐:返回接口

package db

type UserRepository interface {

Create(user User) error

Get(id int) (*User, error)

}

func NewUserRepository() UserRepository {

return &MySQLRepository{}

}

// 所有调用者都必须使用 UserRepository 接口

// 即使他们可能有特殊需求

相比之下,返回具体类型:

// ✅ 推荐:返回具体类型

package db

func NewUserRepository() *MySQLRepository {

return &MySQLRepository{}

}

type MySQLRepository struct { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLRepository) Create(user User) error { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLRepository) Get(id int) (*User, error) { /* ... */ }

func (r *MySQLRepository) SpecialMySQLFeature() { /* ... */ } // 具体类型的特有方法

优势:

- 调用者可以选择直接使用具体类型的所有功能

- 调用者也可以选择仅使用接口(如果需要抽象)

- 不会强制所有调用者使用相同的抽象级别

问题2:依赖方向问题

返回接口可能导致不合理的包依赖关系:

// ❌ 问题:返回接口导致消费者依赖生产者的抽象定义

// producer.go (生产者包)

package producer

type MyInterface interface {

DoSomething()

}

func New() MyInterface {

return &impl{}

}

// consumer.go (消费者包) - 必须导入 producer 包才能使用 MyInterface

package consumer

import "producer"

func Use() {

obj := producer.New() // 类型是 producer.MyInterface

// 现在 consumer 依赖 producer 的接口定义

}

问题3:违背”发现抽象”原则

如果生产者返回接口,等于预先决定了抽象。但根据之前的原则,抽象应该由消费者在需要时自己发现和定义。

为什么应该接受接口作为参数?-> 提高通用性和可测试性

// ✅ 优秀实践:接受接口,返回具体类型

package processor

// 接受接口 - 提高函数通用性

func ProcessData(r io.Reader) error {

// 可以接受文件、网络连接、内存缓冲区等

}

// 返回具体类型 - 给予调用者选择权

func NewProcessor() *ConcreteProcessor {

return &ConcreteProcessor{}

}

何时可以返回接口?-> 在明确知道(而非预见)返回接口会带来实际好处的情况下

- 场景1:提供可选行为的场景

// 标准库的 error 接口是一个很好的例子

// error 是一个极简接口,有明确的契约

type error interface {

Error() string

}

// 返回 error 接口是合理的,因为它定义了一个基本行为

func Parse(input string) (Result, error) {

// 可能返回各种具体的 error 类型

return result, &ParseError{...}

}

- 场景2:工厂模式或策略模式

// 当函数的作用是创建某种策略的实现时

type Logger interface {

Log(message string)

}

// 根据配置返回不同的日志实现

func NewLogger(config Config) Logger {

switch config.Type {

case "file":

return &FileLogger{...}

case "console":

return &ConsoleLogger{...}

default:

return &DefaultLogger{...}

}

}

- 场景3:隐藏内部复杂的实现细节

// 当你不想暴露实现细节时

package cache

type Cache interface {

Get(key string) ([]byte, error)

Set(key string, value []byte) error

}

// New 返回接口,隐藏了具体是哪种缓存实现

func New() Cache {

// 可能使用 Redis、内存或其他

return createComplexCache()

}

8. any says nothing (滥用 any 类型)

TL;DR

Only use

anyif you need to accept or return any possible type, such asjson.Marshal. Otherwise, any doesn’t provide meaningful information and can lead to compile-time issues by allowing a caller to call methods with any data type.

The any type can be helpful if there is a genuine need for accepting or returning any possible type (for instance, when it comes to marshaling or formatting). In general, we should avoid overgeneralizing the code we write at all costs. Perhaps a little bit of duplicated code might occasionally be better if it improves other aspects such as code expressiveness.

仅在真正需要接受或返回任意可能类型时才使用 any(例如 json.Marshal)。否则,any 不会提供有意义的信息,并可能因为允许调用者用任何数据类型调用方法而导致编译时问题。

在 Go 1.18+ 中,any 是空接口 interface{} 的类型别名:

type any = interface{}

这意味着 any 可以容纳任何类型的值,但这恰恰是它最大的危险所在。

package main

func main() {

var i any

i = 42

i = "foo"

i = struct {

s string

}{

s: "bar",

}

i = f

_ = i

}

func f() {}

关键要点:

- any 意味着”没有任何类型信息”:使用它时,你放弃了编译时的类型检查

- 错误从编译时推迟到运行时:这违背了静态类型语言的优势

- 代码可读性下降:读者不知道函数接受什么类型的参数

优先选择其他方案:

- 具体类型(最明确)

- 接口(定义行为)

- 泛型(类型安全的抽象)

记住:少量的重复代码(如为不同类型写相似函数)通常比过度抽象的、使用 any 的代码更好,因为前者更清晰、更安全、更易维护。只有当真正需要处理任意类型时(如序列化、格式化等),才应使用 any。

为什么滥用 any 有害?

失去类型安全性(最严重的问题)

// ❌ 危险的示例

func Process(data any) {

// 为了使用 data,我们需要类型断言

// 但这在编译时无法检查

str := data.(string) // 如果 data 不是 string,运行时会 panic!

fmt.Println(str)

}

func main() {

Process("hello") // 正常

Process(42) // 编译通过,但运行时会 panic!

Process([]int{1,2,3}) // 编译通过,但运行时会 panic!

}

代码意图不清晰

// ❌ 不清晰:这个函数到底接受什么?

func Store(key string, value any) error {

// 什么类型的 value 是合法的?

}

// ✅ 清晰:明确说明接受什么

func StoreString(key string, value string) error

func StoreInt(key string, value int) error

func StoreUser(key string, value User) error

推迟错误到运行时

类型错误应该在编译时捕获,而不是运行时:

// ❌ 错误在运行时才发现

func Calculate(a, b any) any {

return a.(int) + b.(int) // 假设是 int,但不保证

}

// 编译通过,但...

Calculate(10, 20) // 正常:返回 30

Calculate(10, "20") // 编译通过,但运行时会 panic!

Calculate("10", 20) // 编译通过,但运行时会 panic!

// ✅ 更好的方式:使用泛型(Go 1.18+)

func Calculate[T int | float64](a, b T) T {

return a + b // 类型安全,编译时检查

}

何时应该使用 any?

处理未知结构的 JSON 数据

// 这是合理的,因为 JSON 可以是任何结构

func ParseJSON(data []byte) (map[string]any, error) {

var result map[string]any

if err := json.Unmarshal(data, &result); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return result, nil

}

容器数据结构

// 当实现通用容器时(尽管泛型通常是更好的选择)

type Stack struct {

items []any

}

func (s *Stack) Push(item any) {

s.items = append(s.items, item)

}

// 但更好的做法是使用泛型:

type Stack[T any] struct {

items []T

}

格式化和日志

// fmt 包正确使用 any

func Printf(format string, args ...any) (n int, err error)

// 日志记录通常接受 any

log.Printf("User %v logged in at %v", userID, timestamp)

标准库中的合理使用

// encoding/json

func Marshal(v any) ([]byte, error)

// fmt

func Sprintf(format string, a ...any) string

// context

func WithValue(parent Context, key, val any) Context

使用 any 的安全模式

如果必须使用 any,请遵循这些安全模式:

立即进行类型检查

func SafeProcess(value any) error {

switch v := value.(type) {

case string:

return processString(v)

case int:

return processInt(v)

case []byte:

return processBytes(v)

default:

return fmt.Errorf("unsupported type: %T", value)

}

}

使用类型断言的安全形式

func GetString(value any) (string, bool) {

str, ok := value.(string) // 安全断言,不会 panic

return str, ok

}

func main() {

if str, ok := GetString(someValue); ok {

// 安全地使用 str

} else {

// 处理类型不匹配

}

}

约束 any 的使用范围

// 内部使用 any,但对外暴露类型安全的接口

type Processor struct{}

func (p *Processor) processInternal(data any) {

// 内部处理,假设调用者知道规则

}

// 公开的类型安全方法

func (p *Processor) ProcessString(s string) {

p.processInternal(s)

}

func (p *Processor) ProcessInt(i int) {

p.processInternal(i)

}

替代方案:使用泛型(Go 1.18+)

大多数滥用 any 的场景都可以用泛型更好地解决:

// ❌ 使用 any

func FindInSlice(slice []any, target any) int {

for i, v := range slice {

if v == target { // 比较可能不如预期

return i

}

}

return -1

}

// ✅ 使用泛型

func FindInSlice[T comparable](slice []T, target T) int {

for i, v := range slice {

if v == target { // 类型安全的比较

return i

}

}

return -1

}

// 使用

FindInSlice([]string{"a", "b", "c"}, "b") // 正确

FindInSlice([]int{1, 2, 3}, 2) // 正确

// FindInSlice([]string{"a", "b"}, 123) // 编译错误:类型不匹配

9. Being confused about when to use generics (泛型使用不当)

TL;DR

Relying on generics and type parameters can prevent writing boilerplate code to factor out elements or behaviors. However, do not use type parameters prematurely, but only when you see a concrete need for them. Otherwise, they introduce unnecessary abstractions and complexity.

More: Being confused about when to use generics

核心观点:依赖泛型和类型参数可以避免编写提取元素或行为的样板代码。但是,不要过早使用类型参数,只有在看到具体需要时才使用它们。否则,它们会引入不必要的抽象和复杂性。

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sort"

)

func getKeys(m any) ([]any, error) {

switch t := m.(type) {

default:

return nil, fmt.Errorf("unknown type: %T", t)

case map[string]int:

var keys []any

for k := range t {

keys = append(keys, k)

}

return keys, nil

case map[int]string:

// ...

}

return nil, nil

}

func getKeysGenerics[K comparable, V any](m map[K]V) []K {

var keys []K

for k := range m {

keys = append(keys, k)

}

return keys

}

type customConstraint interface {

~int | ~string

}

func getKeysWithConstraint[K customConstraint, V any](m map[K]V) []K {

return nil

}

type Node[T any] struct {

Val T

next *Node[T]

}

func (n *Node[T]) Add(next *Node[T]) {

n.next = next

}

type SliceFn[T any] struct {

S []T

Compare func(T, T) bool

}

func (s SliceFn[T]) Len() int { return len(s.S) }

func (s SliceFn[T]) Less(i, j int) bool { return s.Compare(s.S[i], s.S[j]) }

func (s SliceFn[T]) Swap(i, j int) { s.S[i], s.S[j] = s.S[j], s.S[i] }

func main() {

s := SliceFn[int]{

S: []int{3, 2, 1},

Compare: func(a, b int) bool {

return a < b

},

}

sort.Sort(s)

fmt.Println(s.S)

}

10. Not being aware of the possible problems with type embedding (类型嵌入风险)

TL;DR

Using type embedding can also help avoid boilerplate code; however, ensure that doing so doesn’t lead to visibility issues where some fields should have remained hidden.

核心观点:使用类型嵌入可以帮助避免样板代码,但要确保这样做不会导致可见性问题,即某些本应保持隐藏的字段被意外暴露。

When creating a struct, Go offers the option to embed types. But this can sometimes lead to unexpected behaviors if we don’t understand all the implications of type embedding. Throughout this section, we look at how to embed types, what these bring, and the possible issues.

In Go, a struct field is called embedded if it’s declared without a name. For example,

type Foo struct {

Bar // Embedded field

}

type Bar struct {

Baz int

}

In the Foo struct, the Bar type is declared without an associated name; hence, it’s an embedded field.

We use embedding to promote the fields and methods of an embedded type. Because Bar contains a Baz field, this field is promoted to Foo. Therefore, Baz becomes available from Foo.

What can we say about type embedding? First, let’s note that it’s rarely a necessity, and it means that whatever the use case, we can probably solve it as well without type embedding. Type embedding is mainly used for convenience: in most cases, to promote behaviors.

If we decide to use type embedding, we need to keep two main constraints in mind:

-

It shouldn’t be used solely as some syntactic sugar to simplify accessing a field (such as

Foo.Baz()instead ofFoo.Bar.Baz()). If this is the only rationale, let’s not embed the inner type and use a field instead. -

It shouldn’t promote data (fields) or a behavior (methods) we want to hide from the outside: for example, if it allows clients to access a locking behavior that should remain private to the struct.

Using type embedding consciously by keeping these constraints in mind can help avoid boilerplate code with additional forwarding methods. However, let’s make sure we don’t do it solely for cosmetics and not promote elements that should remain hidden.

示例代码:

package main

import (

"io"

"os"

"sync"

)

type Foo struct {

Bar

}

type Bar struct {

Baz int

}

func fooBar() {

foo := Foo{}

foo.Baz = 42

}

type InMem struct {

sync.Mutex

m map[string]int

}

func New() *InMem {

return &InMem{m: make(map[string]int)}

}

func (i *InMem) Get(key string) (int, bool) {

i.Lock()

v, contains := i.m[key]

i.Unlock()

return v, contains

}

type Logger struct {

writeCloser io.WriteCloser

}

func (l Logger) Write(p []byte) (int, error) {

return l.writeCloser.Write(p)

}

func (l Logger) Close() error {

return l.writeCloser.Close()

}

func main() {

l := Logger{writeCloser: os.Stdout}

_, _ = l.Write([]byte("foo"))

_ = l.Close()

}

什么是类型嵌入?

类型嵌入是 Go 中结构体字段的一种特殊声明方式,字段没有名称,只有类型:

type Foo struct {

Bar // 嵌入字段,没有字段名,只有类型

}

type Bar struct {

Baz int

}

在 Foo 结构体中,Bar 类型被嵌入,因此 Bar 的字段和方法会被”提升”到 Foo 中,可以直接通过 Foo 访问。

类型嵌入的主要用途

- (1) 方法提升:嵌入类型的方法会被提升到外层类型,可以避免编写转发方法

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type File struct {

*os.File // 嵌入,File 现在有了 Read 方法

}

// 无需编写转发方法:

// func (f File) Read(p []byte) (n int, err error) {

// return f.File.Read(p)

// }

- (2) 接口实现:通过嵌入,外层类型自动实现了内层类型实现的接口

type MyReader struct {

io.Reader // 嵌入,MyReader 自动实现了 io.Reader 接口

}

类型嵌入的潜在问题

- (1) 意外暴露私有字段和方法

// 问题示例:意外暴露内部实现

type Account struct {

sync.Mutex // 嵌入锁

balance float64

}

func main() {

acc := Account{}

acc.Lock() // ⚠️ 问题:外部可以直接调用锁的方法

acc.Unlock() // 这破坏了封装性

}

问题:sync.Mutex 的 Lock() 和 Unlock() 方法被提升到 Account,外部代码可以直接控制锁,可能导致:死锁风险,锁状态管理混乱,破坏了数据封装的完整性。

- (2) 命名冲突和歧义

type A struct{}

func (A) Process() { fmt.Println("A.Process") }

type B struct{}

func (B) Process() { fmt.Println("B.Process") }

type C struct {

A

B

}

func main() {

c := C{}

// c.Process() // ⚠️ 编译错误:ambiguous selector c.Process

// 必须明确指定:

c.A.Process() // 正确

c.B.Process() // 正确

}

- (3) 接口实现冲突

type Writer interface {

Write(data []byte) error

}

type FileWriter struct {

Writer // 嵌入接口

}

// 问题:FileWriter 没有实现 Write 方法

// 但在编译时不会报错,直到运行时才可能发现

- (4) 过度提升导致 API 污染

type Config struct {

// 嵌入过多的类型可能导致 API 过于复杂

DatabaseConfig

CacheConfig

APIConfig

LoggingConfig

// 所有嵌入类型的公共方法都会被提升

}

// 使用 Config 时,会有大量方法可用,但很多可能是不相关的

使用类型嵌入的最佳实践

- (1) 仅在需要行为提升时使用

// ✅ 正确:需要提升 io.Reader 的行为

type BufferedReader struct {

io.Reader // 嵌入,为了获得 Read 方法

buffer []byte

}

// ❌ 错误:仅仅为了语法糖

type User struct {

Address // 嵌入,只是为了能写 user.City 而不是 user.Address.City

}

// ✅ 更好:使用命名字段

type User struct {

addr Address // 命名字段,访问需要 user.addr.City

}

- (2) 不要嵌入应该隐藏的类型

// ❌ 错误:暴露内部同步机制

type SafeCounter struct {

sync.Mutex

count int

}

// ✅ 正确:将锁作为私有字段

type SafeCounter struct {

mu sync.Mutex // 私有字段,不暴露 Mutex 的方法

count int

}

func (sc *SafeCounter) Increment() {

sc.mu.Lock()

defer sc.mu.Unlock()

sc.count++

}

- (3) 优先组合而非继承思维

// Go 鼓励组合而非继承

type Server struct {

// 明确组合各个组件

httpServer *http.Server

router *mux.Router

logger *log.Logger

}

// 而不是:

type Server struct {

*http.Server // 嵌入可能导致不必要的方法提升

*mux.Router

*log.Logger

}

- (4) 谨慎处理接口嵌入

// ✅ 正确使用接口嵌入

type ReadWriter interface {

io.Reader

io.Writer

}

// 小心:确保类型确实实现了接口

type MyType struct {

io.Writer // 嵌入接口

}

func NewMyType(w io.Writer) *MyType {

return &MyType{Writer: w} // 确保传入的 w 不为 nil

}

记住:类型嵌入是工具,不是必需品。在 Go 中,几乎总能通过不使用类型嵌入来解决问题。只有当它真正简化了代码且不会导致可见性问题时,才应该使用它。

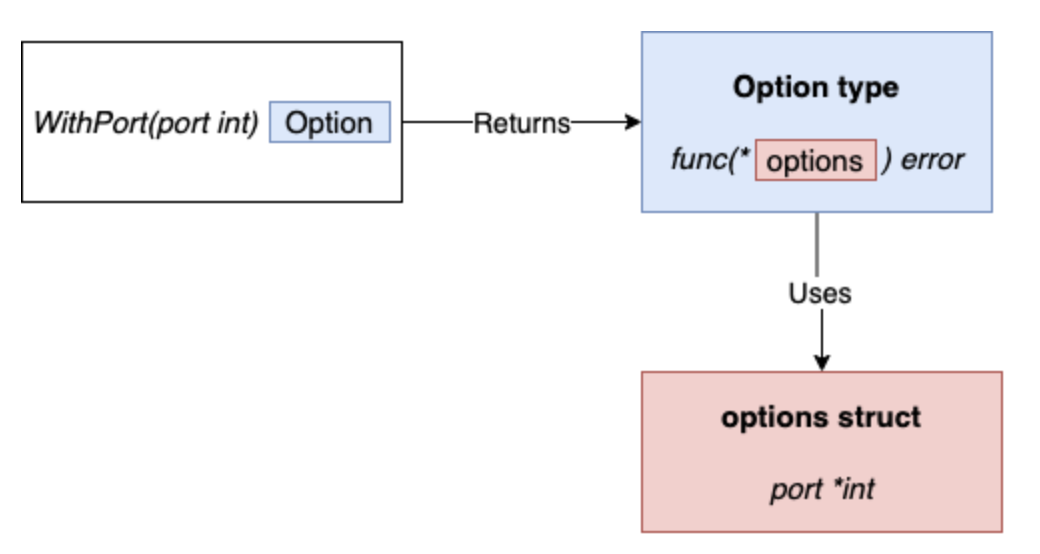

11. Not using the functional options pattern (缺少函数选项模式)

TL;DR

To handle options conveniently and in an API-friendly manner, use the functional options pattern.

核心观点:为了以方便且 API 友好的方式处理选项,请使用函数选项模式。这是一种优雅处理可选参数和配置的方法。

Although there are different implementations with minor variations, the main idea is as follows:

- An unexported struct holds the configuration: options.

- Each option is a function that returns the same type:

type Option func(options *options) error. For example,WithPortaccepts anintargument that represents the port and returns anOptiontype that represents how to update theoptionsstruct.

type options struct {

port *int

}

type Option func(options *options) error

func WithPort(port int) Option {

return func(options *options) error {

if port < 0 {

return errors.New("port should be positive")

}

options.port = &port

return nil

}

}

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...Option) ( *http.Server, error) {

var options options

for _, opt := range opts {

err := opt(&options)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

// At this stage, the options struct is built and contains the config

// Therefore, we can implement our logic related to port configuration

var port int

if options.port == nil {

port = defaultHTTPPort

} else {

if *options.port == 0 {

port = randomPort()

} else {

port = *options.port

}

}

// ...

}

The functional options pattern provides a handy and API-friendly way to handle options. Although the builder pattern can be a valid option, it has some minor downsides (having to pass a config struct that can be empty or a less handy way to handle error management) that tend to make the functional options pattern the idiomatic way to deal with these kind of problems in Go.

为什么需要函数选项模式?

在 Go 中,函数通常有多个配置选项,传统的解决方法有以下问题:

- (1) 配置结构体问题

// ❌ 问题:需要传入完整配置结构体,即使很多字段是默认值

type Config struct {

Port int

Timeout time.Duration

Logger Logger

// ... 更多字段

}

func NewServer(addr string, cfg Config) *Server {

// 即使只需要设置 Port,也要创建完整 Config

}

// 使用:

server := NewServer(":8080", Config{

Port: 8080,

Timeout: 30 * time.Second, // 必须指定默认值

Logger: nil, // 必须明确传递 nil

})

- (2) 多参数问题

// ❌ 问题:参数太多,难以记忆和维护

func NewServer(addr string, port int, timeout time.Duration,

logger Logger, maxConns int, tlsConfig *tls.Config) *Server {

// 参数顺序重要,且必须传递所有参数

}

- (3) 变长参数使用基础类型

// ❌ 问题:类型不安全,可读性差

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...interface{}) *Server {

// 需要类型断言,容易出错

}

函数选项模式解决方案

基本结构

// 1. 非导出配置结构体

type options struct {

port *int

timeout time.Duration

logger Logger

maxConns int

}

// 2. Option 函数类型

type Option func(*options) error

// 3. 选项构造函数(通常以 With 开头)

func WithPort(port int) Option {

return func(o *options) error {

if port < 0 || port > 65535 {

return errors.New("invalid port")

}

o.port = &port

return nil

}

}

func WithTimeout(timeout time.Duration) Option {

return func(o *options) error {

if timeout < 0 {

return errors.New("timeout must be positive")

}

o.timeout = timeout

return nil

}

}

func WithLogger(logger Logger) Option {

return func(o *options) error {

if logger == nil {

return errors.New("logger cannot be nil")

}

o.logger = logger

return nil

}

}

// 4. 构造函数使用可变参数接受选项

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...Option) (*Server, error) {

// 设置默认值

config := options{

port: nil, // 使用指针表示可选

timeout: 30 * time.Second,

logger: defaultLogger,

maxConns: 100,

}

// 应用所有选项

for _, opt := range opts {

if err := opt(&config); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("applying option: %w", err)

}

}

// 最终配置处理

var port int

if config.port == nil {

port = defaultPort

} else {

port = *config.port

}

// 创建并返回 Server

return &Server{

addr: addr,

port: port,

timeout: config.timeout,

logger: config.logger,

}, nil

}

使用示例

// 只设置需要的选项,顺序无关

server1, err := NewServer("localhost")

server2, err := NewServer("localhost",

WithPort(8080),

WithTimeout(60*time.Second),

)

server3, err := NewServer("localhost",

WithLogger(customLogger),

WithPort(9000),

)

函数选项模式是 Go 社区广泛接受的配置模式,特别是在标准库和流行开源项目中常见。它提供了优秀的 API 体验,同时保持了代码的简洁和可维护性。

12. Project misorganization (project structure and package organization) (项目结构与包名管理)

Regarding the overall organization, there are different schools of thought. For example, should we organize our application by context or by layer? It depends on our preferences. We may favor grouping code per context (such as the customer context, the contract context, etc.), or we may favor following hexagonal(六边形的) architecture principles and group per technical layer. If the decision we make fits our use case, it cannot be a wrong decision, as long as we remain consistent with it.

Regarding packages, there are multiple best practices that we should follow. First, we should avoid premature packaging because it might cause us to overcomplicate a project. Sometimes, it’s better to use a simple organization and have our project evolve when we understand what it contains rather than forcing ourselves to make the perfect structure up front. Granularity is another essential thing to consider. We should avoid having dozens of nano packages containing only one or two files. If we do, it’s because we have probably missed some logical connections across these packages, making our project harder for readers to understand. Conversely, we should also avoid huge packages that dilute the meaning of a package name.

Package naming should also be considered with care. As we all know (as developers), naming is hard. To help clients understand a Go project, we should name our packages after what they provide, not what they contain. Also, naming should be meaningful. Therefore, a package name should be short, concise, expressive, and, by convention, a single lowercase word.

Regarding what to export, the rule is pretty straightforward. We should minimize what should be exported as much as possible to reduce the coupling between packages and keep unnecessary exported elements hidden. If we are unsure whether to export an element or not, we should default to not exporting it. Later, if we discover that we need to export it, we can adjust our code. Let’s also keep in mind some exceptions, such as making fields exported so that a struct can be unmarshaled with encoding/json.

Organizing a project isn’t straightforward, but following these rules should help make it easier to maintain. However, remember that consistency is also vital to ease maintainability. Therefore, let’s make sure that we keep things as consistent as possible within a codebase.

Note: In 2023, the Go team has published an official guideline for organizing / structuring a Go project: go.dev/doc/modules/layout

核心观点:项目组织没有单一标准答案,但遵循一些最佳实践可以使代码更易维护。关键在于保持一致性,选择适合团队和项目的方式。

项目结构组织方式

按业务上下文组织 vs 按技术层组织

建议:没有绝对正确,选择后保持一致性。Go社区倾向于按业务上下文组织。

按业务上下文(领域驱动)

project/

customer/ # 客户上下文

handler.go

service.go

repository.go

model.go

order/ # 订单上下文

handler.go

service.go

repository.go

model.go

product/ # 产品上下文

handler.go

service.go

repository.go

model.go

优点:

- 高内聚:相关业务逻辑集中在一起

- 易于维护:修改某个功能时只需关注单个目录

- 符合微服务趋势:便于未来拆分为独立服务

- 按技术层(分层架构)

project/

handlers/ # 控制层

customer_handler.go

order_handler.go

product_handler.go

services/ # 业务逻辑层

customer_service.go

order_service.go

product_service.go

repositories/ # 数据访问层

customer_repo.go

order_repo.go

product_repo.go

models/ # 数据模型

customer.go

order.go

product.go

优点:

- 关注点分离:每层有明确职责

- 技术栈统一:同类技术放在一起

- 传统模式:许多团队熟悉此模式

包组织最佳实践

(1) 避免过早分包

原则:让项目自然演进,不要一开始就设计复杂结构。

// 初期:从简单开始

project/

main.go # 包含所有逻辑

utils.go # 辅助函数

// 中期:按需拆分

project/

cmd/

server/

main.go # 入口

internal/

api/ # API相关

db/ # 数据库操作

models/ # 数据模型

// 成熟期:精细组织

project/

cmd/

server/

main.go

internal/

user/ # 用户模块

order/ # 订单模块

product/ # 产品模块

pkg/

utils/ # 可复用的工具

config/ # 配置管理

(2) 包的粒度要适中

// ❌ 过于细粒度(纳米包)

project/

pkg/

stringutil/ # 仅包含2-3个字符串函数

intutil/ # 仅包含2-3个整数函数

timeutil/ # 仅包含2-3个时间函数

// ❌ 过于粗粒度(巨型包)

project/

pkg/

utils/ # 包含数百个不相关的函数

# 名称失去意义

// ✅ 适度粒度

project/

pkg/

strutil/ # 字符串相关工具

mathutil/ # 数学计算工具

timeutil/ # 时间日期工具(包含相关功能)

(3) 包命名要明确

// ❌ 糟糕的命名

common/ # 太泛,不知道提供什么

util/ # 不知道具体用途

helper/ # 不清楚帮助什么

misc/ # 杂物堆

// ✅ 好的命名

validator/ # 提供验证功能

formatter/ # 提供格式化功能

authenticator/ # 提供认证功能

cache/ # 提供缓存功能

// 规则:

// 1. 使用单数名词:user 而不是 users

// 2. 简短但描述性:log 而不是 loggingfacility

// 3. 避免缩写:strconv(允许) vs stcv(避免)

(4) 最小化导出

导出原则:

- 默认不导出,需要时再公开

- 只导出必要的接口和函数

- 内部实现保持私有

// 内部包结构

package cache

// 导出必须的接口

type Cache interface {

Get(key string) ([]byte, error)

Set(key string, value []byte) error

}

// 不导出具体实现

type redisCache struct {

client *redis.Client

}

// 导出工厂函数

func NewRedisCache(addr string) (Cache, error) {

return &redisCache{

client: connectRedis(addr),

}, nil

}

// 不导出的辅助函数

func connectRedis(addr string) *redis.Client {

// 内部实现细节

}

(5) 处理 JSON 序列化等特殊情况

type User struct {

// 字段必须导出才能被 encoding/json 访问

ID int `json:"id"`

Name string `json:"name"`

Email string `json:"email,omitempty"`

// 不导出的字段不会被序列化

passwordHash string

}

项目结构模板示例

标准 Go 项目布局(参考)

myproject/

├── cmd/ # 可执行程序入口

│ ├── myapp/

│ │ └── main.go # 主程序

│ └── mytool/

│ └── main.go # 工具程序

├── internal/ # 私有应用代码

│ ├── api/ # API 层

│ ├── service/ # 业务逻辑层

│ ├── repository/ # 数据访问层

│ └── model/ # 数据模型

├── pkg/ # 可公开导入的库代码

│ ├── libfoo/ # 库包 A

│ └── libbar/ # 库包 B

├── api/ # API 定义(protobuf, OpenAPI)

├── web/ # Web 资源

├── configs/ # 配置文件

├── init/ # 初始化脚本

├── scripts/ # 构建/部署脚本

├── build/ # 构建输出

├── deployments/ # 部署配置

├── test/ # 测试数据

├── docs/ # 文档

├── tools/ # 开发工具

├── examples/ # 示例代码

├── vendor/ # 依赖(可选)

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

└── README.md

微服务项目结构

microservice/

├── cmd/

│ └── server/

│ └── main.go

├── internal/

│ ├── handler/ # HTTP/gRPC 处理器

│ ├── service/ # 业务逻辑实现

│ ├── repository/ # 数据持久化

│ ├── domain/ # 领域模型

│ ├── middleware/ # 中间件

│ └── config/ # 配置读取

├── pkg/

│ ├── logger/ # 日志组件

│ ├── database/ # 数据库封装

│ └── validator/ # 验证器

├── api/

│ └── v1/ # API 协议定义

├── deployments/

│ ├── docker/

│ └── kubernetes/

├── migrations/ # 数据库迁移

├── scripts/ # 脚本

└── tests/ # 测试

关键实践总结

Do’s(应该做的)

- 从简单开始:开始时用扁平结构,需要时再重构

- 保持一致性:选定模式后,整个项目保持一致

- 合理命名:包名描述功能,而不是内容

- 最小化公开 API:只导出必要的部分

- 考虑可读性:让新成员能快速理解结构

Don’ts(不应该做的)

- 不要过度设计:避免过早优化项目结构

- 不要创建太多小包:避免”纳米包”综合症

- 不要使用无意义的包名:如

common、utils - 不要随意导出:默认私有,需要时再公开

- 不要忽略团队约定:遵循团队已有的模式

决策指南

当不确定如何组织时,问这些问题:

- 项目规模:小型项目用简单结构,大型项目需要更细致的组织

- 团队规模:大团队需要更规范的结构,小团队可以更灵活

- 部署方式:单体应用 vs 微服务影响结构选择

- 维护周期:长期维护的项目需要更稳健的结构

- 外部依赖:是否作为库供他人使用?

最后记住:没有完美的结构,只有适合当前项目的结构。随着项目演进,结构也需要调整。重要的是保持代码清晰、可维护,并让团队成员都能理解和遵循。

13. Creating utility packages (避免使用通用、无意义的包名)

TL;DR

Naming is a critical piece of application design. Creating packages such as common, util, and shared doesn’t bring much value for the reader. Refactor such packages into meaningful and specific package names.

Also, bear in mind that naming a package after what it provides and not what it contains can be an efficient way to increase its expressiveness.

核心观点:避免使用通用、无意义的包名(如 common, util, shared),而应使用具体、有意义的名称。

这条建议的本质是:通过有目的性的包命名来驱动更好的软件设计。它强迫你思考每个类的单一职责和逻辑归属,从而产生更模块化、更易于理解和更健壮的代码结构。拒绝“杂物抽屉”,拥抱“精心整理的工具箱”。

为什么 util、common 这类包名不好?

- 成为“杂物抽屉”

- 像

utils或common这样的包,很容易变成一个什么都可以往里扔的“万能包”。随着项目增长,它会包含各种不相关的类:日期处理、字符串工具、加密助手、日志格式化、DTO 对象等等。 - 这违反了高内聚、低耦合的原则。包内的类之间几乎没有逻辑关联。

- 像

- 对读者毫无价值

- 当你看到一个导入语句是

from com.example.util import StringHelper时,util这个词没有传达任何关于StringHelper功能、所属领域或依赖关系的有效信息。 - 开发者必须深入查看代码才能理解这个类的用途和上下文。

- 当你看到一个导入语句是

- 隐藏设计缺陷

- 将一些类随意放入

util,可能会掩盖它们在领域模型中的正确位置。例如,一个OrderValidator本应属于order领域包,却被错误地放入了common.validation中,割裂了其与业务逻辑的联系。

- 将一些类随意放入

解决方案:创建有意义的包

原则是:以包“提供什么”或“属于哪个领域”来命名,而不是以它“包含什么杂项”来命名。

- 按功能/提供的能力分组

将“杂物抽屉”拆分成多个目的明确的小包。

反面例子:

com.company.util -> 包含 DateUtil, FileUtil, HttpUtil, EncryptionUtil

正面重构:这样,从包名就能立刻知道其核心职责

com.company.**time**.DateParser (专注于时间相关)

com.company.**io**.FileReader (专注于输入输出)

com.company.**http**.client.HttpClient (专注于HTTP通信)

com.company.**security**.encryption.Encryptor (专注于安全)

- 按领域/模块分组

将工具类划分到它们所服务的特定业务领域或模块中。

反面例子:

com.company.common -> 包含 OrderHelper, UserDto, ConfigConstants

正面重构:这强化了领域边界,让代码与业务结构对齐

com.company.**order**.domain.OrderIdGenerator (属于order领域)

com.company.**user**.dto.UserResponse (属于user领域)

com.company.**configuration**.AppConfig (属于配置领域)

平衡与例外

当然,在非常小的项目或原型中,一个 utils 包可能无可厚非。但一旦项目开始增长,遵循这一原则将极大地提升代码的可读性、可维护性和架构清晰度。

14. Ignoring package name collisions (变量名与包名发生冲突)

TL;DR

To avoid naming collisions between variables and packages, leading to confusion or perhaps even bugs, use unique names for each one. If this isn’t feasible, use an import alias to change the qualifier to differentiate the package name from the variable name, or think of a better name.

Package collisions occur when a variable name collides with an existing package name, preventing the package from being reused. We should prevent variable name collisions to avoid ambiguity. If we face a collision, we should either find another meaningful name or use an import alias.

核心问题:在 Go 中,当变量名、函数名或其他标识符与包名发生冲突时,会导致编译错误或混淆。特别是在使用包别名时,需要特别注意命名冲突。

包导入与局部变量冲突

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// 问题:变量名与包名相同

fmt := "some string" // 这会覆盖 fmt 包的作用域

fmt.Println("Hello") // 编译错误:fmt.Println 未定义(现在 fmt 是字符串)

}

多包同名冲突

package main

import (

"github.com/user/config" // 第三方 config 包

"myproject/config" // 本地 config 包 - 冲突!

)

func main() {

// 两个包都叫 config,无法同时导入

}

包别名与标识符冲突

package main

import (

json "encoding/json" // 包别名

"fmt"

)

func main() {

json := "some data" // 变量名与包别名冲突

// 现在无法使用 json 包

}

解决方案:使用包别名

package main

import (

"fmt"

myConfig "github.com/user/config" // 为第三方包设置别名

localConfig "myproject/config" // 为本地包设置别名

)

func main() {

fmt := "formatted string" // 局部变量

// 使用别名访问包

config := myConfig.Load()

localCfg := localConfig.Default()

}

在 Go 中处理包名冲突,优先使用有意义的包别名,其次考虑重命名局部标识符。Go 的静态类型系统和严格的导入规则使得提前发现和解决命名冲突变得更加重要。遵循”显式优于隐式”的原则,使用清晰的别名可以显著提高代码的可读性和可维护性。

15. Missing code documentation (缺少代码文档)

TL;DR

To help clients and maintainers understand your code’s purpose, document exported elements.

Documentation is an important aspect of coding. It simplifies how clients can consume an API but can also help in maintaining a project. In Go, we should follow some rules to make our code idiomatic:

First, every exported element must be documented. Whether it is a structure, an interface, a function, or something else, if it’s exported, it must be documented. The convention is to add comments, starting with the name of the exported element.

As a convention, each comment should be a complete sentence that ends with punctuation. Also bear in mind that when we document a function (or a method), we should highlight what the function intends to do, not how it does it; this belongs to the core of a function and comments, not documentation. Furthermore, the documentation should ideally provide enough information that the consumer does not have to look at our code to understand how to use an exported element.

When it comes to documenting a variable or a constant, we might be interested in conveying two aspects: its purpose and its content. The former should live as code documentation to be useful for external clients. The latter, though, shouldn’t necessarily be public.

To help clients and maintainers understand a package’s scope, we should also document each package. The convention is to start the comment with // Package followed by the package name. The first line of a package comment should be concise. That’s because it will appear in the package. Then, we can provide all the information we need in the following lines.

Documenting our code shouldn’t be a constraint. We should take the opportunity to make sure it helps clients and maintainers to understand the purpose of our code.

核心原则:所有导出的元素都必须有文档。Go 语言通过文档注释(doc comments)来生成官方文档,这是 Go 生态系统的核心组成部分。

必须文档化的内容

(1) 包级文档(Package Documentation)

每个包都必须有包级文档,通常放在包声明的上方:

// Package httputil provides HTTP utility functions, complementing the

// more common ones in the net/http package.

//

// This package includes:

// - Request/response debugging helpers

// - HTTP client utilities

// - Common middleware components

package httputil

规范要求:

- 第一行以

Package <包名>开头 - 第一行简洁描述包的核心功能

- 后续行提供更详细的信息

- 显示在

go doc和pkg.go.dev上

(2) 导出函数/方法文档

// ValidateUser checks if the provided user meets all business requirements.

// It validates the user's email format, password strength, and required fields.

// Returns nil if validation passes, or ValidationError if any check fails.

//

// Example:

// err := ValidateUser(user)

// if err != nil {

// return err

// }

func ValidateUser(user User) error {

// 实现细节

}

规范要求:

- 描述”做什么”,不是”怎么做” - 重点在意图而非实现

- 使用完整句子,以句号结尾

- 提供使用示例(如果复杂)

- 说明参数、返回值、错误情况

(3) 导出类型/结构体文档

// Config holds application configuration settings.

// This struct is safe for concurrent use after initialization.

type Config struct {

// Host is the server hostname or IP address.

Host string `json:"host"`

// Port is the server port number (default: 8080).

Port int `json:"port"`

// Timeout is the request timeout in seconds.

Timeout int `json:"timeout"`

}

(4) 导出变量/常量文档

// DefaultPort is the default HTTP port used when none is specified.

const DefaultPort = 8080

// ErrInvalidInput is returned when user input fails validation.

var ErrInvalidInput = errors.New("invalid input")

Go 文档的独特优势

工具链深度集成

# 查看包文档

go doc net/http

# 查看特定函数

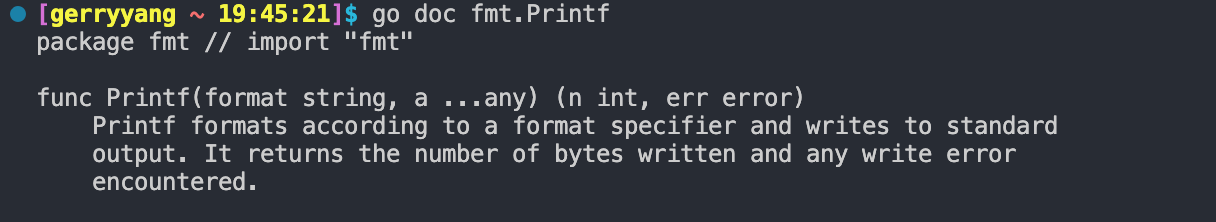

go doc fmt.Printf

# 启动本地文档服务器

godoc -http=:6060

文档生成工具链

(1) 标准工具

# 格式化文档注释

go fmt ./...

# 检查文档完整性

go vet ./...

# 专门的文档检查工具

golang.org/x/tools/go/analysis/passes/doc

(2) 生成 HTML 文档

# 生成包文档网站

godoc -url /pkg/your-package > docs.html

# 使用pkgsite(Go 1.16+)

go install golang.org/x/pkgsite/cmd/pkgsite@latest

pkgsite

为什么 Go 特别强调文档

- Go 文档是公开 API 契约:

pkg.go.dev自动为所有公共包生成文档 - 文档驱动开发文化:Go 社区优先考虑清晰、简洁的 API 文档

- 工具链强制执行:

go vet会检查缺失的文档 - 文档影响包的可发现性:良好的文档提高包的采用率

在 Go 中,文档不是可选的附加品,而是代码的核心组成部分。良好的文档:

- 减少使用成本:用户无需阅读源代码

- 提高维护性:清晰的意图说明

- 增强可靠性:示例即测试

- 促进代码重用:清晰的API契约

- 遵循”文档优先”的原则,把文档作为设计过程的一部分,而不是事后补充。正如 Rob Pike 所说:”文档是给用户看的,注释是给维护者看的。”

16. Not using linters (未使用 linters)

TL;DR

To improve code quality and consistency, use linters and formatters.

A linter is an automatic tool to analyze code and catch errors. The scope of this section isn’t to give an exhaustive list of the existing linters; otherwise, it will become deprecated pretty quickly. But we should understand and remember why linters are essential for most Go projects.

However, if you’re not a regular user of linters, here is a list that you may want to use daily:

- https://golang.org/cmd/vet—A standard Go analyzer

- https://github.com/kisielk/errcheck—An error checker

- https://github.com/fzipp/gocyclo—A cyclomatic complexity analyzer

- https://github.com/jgautheron/goconst—A repeated string constants analyzer

Besides linters, we should also use code formatters to fix code style. Here is a list of some code formatters for you to try:

- https://golang.org/cmd/gofmt—A standard Go code formatter

- https://godoc.org/golang.org/x/tools/cmd/goimports—A standard Go imports formatter

Meanwhile, we should also look at golangci-lint (https://github.com/golangci/golangci-lint). It’s a linting tool that provides a facade on top of many useful linters and formatters. Also, it allows running the linters in parallel to improve analysis speed, which is quite handy.

Linters and formatters are a powerful way to improve the quality and consistency of our codebase. Let’s take the time to understand which one we should use and make sure we automate their execution (such as a CI or Git precommit hook).

核心观点:使用 linter 和格式化工具是提高 Go 代码质量的关键实践。它们能自动发现潜在问题、保持代码一致性,并强制执行最佳实践。

Data Types

17. Creating confusion with octal literals

Refer

- https://github.com/teivah/100-go-mistakes

- https://100go.co/